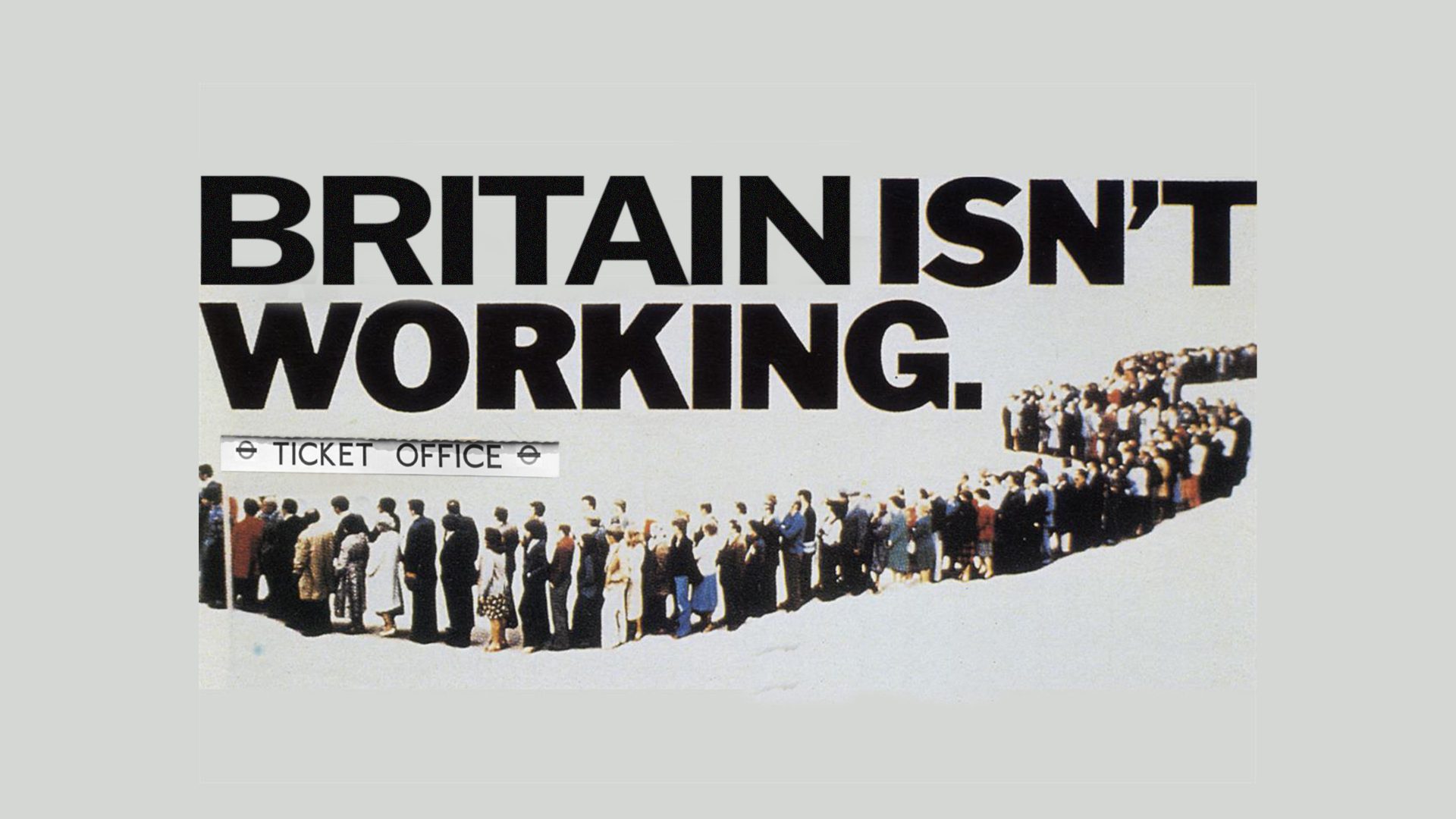

As the news broke just before Christmas that the UK economy has not grown since Labour came into office, the old Conservative taunt that “Labour isn’t Working” could be right. What is even more painful is that this is a government that came in promising to reform the world of work. What are Labour’s challenges when it comes to work?

Five years after Covid, one fifth of all UK adults of working age are now classified as “economically inactive”, meaning they are unwilling or unable to work as they did before.

While the Get Britain Working Again White Paper published in November promised “an ambitious 80 per cent employment rate” the real issue is not the rate of employment – currently just under 75% – but worklessness.

Stress and ill health are one part of a “workdemic”, the other elements being rising inflation, low wage growth, and the ill effects of Rachel Reeves’s budget, which imposed a £25bn National Insurance hit on employers. Bloomberg Economics estimates a direct cost of 130,000 jobs as a result. A substantial part of that number of workers will be shifted away from payroll and into the more precarious, freelance economy.

Something else is going on, which is less economic than cultural: Labour seems to be failing to read the room when it comes to work. The roots of what the British feel about work lie in our culture and in plain sight: for many people work is toxic, inflexible, and dehumanising.

It’s one thing to argue for fair pay and “the right to disconnect” for a better work life balance, but it is another to demand what Labour currently isn’t addressing at all – namely better management and better organisation. Productivity is linked to wellbeing and engagement: this isn’t currently in Labour’s approach to the issue of work. It needs to be.

2025 isn’t just the fifth anniversary of the pandemic which lifted the lid on so much about how we feel about work. It’s also the fiftieth anniversary of one of the BBC’s most popular sitcoms, The Good Life, which ran for 78 episodes from April 1975 and whose central plot device was of a “corporation man” who had stepped back from the business world and was growing vegetables instead.

One of the most popular British TV exports around the world is Ricky Gervais’s The Office, a weary and at times caustic examination of humdrum office life. During the pandemic, Americans streamed 57 billion minutes of it on Netflix, making it their most downloaded show.

The ennui about work isn’t confined to older workers – far from it. GenZ, which by 2030 will make up a third of the workforce, is a notoriously values- and purpose-led group, which is unwilling to just show up. They distrust the always-in-aways-on model shown to them by their parents.

All of which is to say that Labour cannot keep promising empty metrics when it comes to improving how we work. It has to show an integrated approach to what we feel and – as importantly, how we live as well as work. And this is where we have to talk about AI.

The Human in the Machine

Current shifts in working practices are causing upheaval comparable to the arrival of the assembly line a century ago. For the first time, white collar workers are experiencing the chill of technological transformation, previously reserved for their blue-collar colleagues. This explains Labour’s announcement, within a month of taking office, of a £30m investment across 100 AI-related projects, covering a range of challenges from how NHS prescriptions are dispensed to health and safety in the construction industry.

But investing isn’t enough. Labour has to train people with the right skills. Perhaps this explains why Euan Blair’s “edtech” Multiverse training company is doing so well and recently posted on LinkedIn: “This week I had the pleasure of welcoming Minister for Skills Jacqui Smith to Multiverse HQ & to join a small session with chancellor Rachel Reeves alongside Founders Forum Group and Meta.”

Assembling such a powerful group isn’t just down to the networks of the son of the former prime minister, but testament to the fact that work itself is at risk of redundancy if we don’t keep up with the AI coming at us.

The UK is the third largest AI market in the world after the US and China. Perhaps that’s why Rishi Sunak appeared awestruck (possibly dumbstruck) when Elon Musk famously told him at Bletchley Park that “you can have a job if you want for personal satisfaction, but AI will do everything”.

But Rishi Sunak misread the room too. People don’t want to be dehumanised by AI or worse, replaced by it. They are probably biddable when it comes to working alongside it (although I predict a better phrase than Microsoft’s “Co-pilot” is coming down that track). It’s necessary to challenge the rising narrative, heavily promoted by Silicon Valley, that work is somehow not such a big deal and that life would be so much more fun if robots and AI assistants did it all for us.

Labour currently has no story to tell on this, no nuance in between the rigid policy announcements. Understanding the culture of work – the custom as well as the practice – is critical to creating a successful and workable strategy.

A brief word about networks. Never has there been a more necessary time for them and now is the time to lay to rest the mistaken belief that they are confined to “elites” and the well connected. The ability to develop networks at work is a cost-effective and highly meritocratic way to “level up”. The most famous essay ever written on this, by the sociologist Mark Granovetter, The Strength of Weak Ties, showed this. The ability to find work in an increasingly contract and freelance-based world, where no matter how good the employment rights protections are, it will be crucial to make good and quick connections in perhaps several workplaces at once – this will matter a great deal.

Networks also matter in a hybrid world where well over 90% of all meetings will always have at least one person attending remotely. The evidence suggests that while systems to democratise access to jobs and careers with such techniques as “blind hiring” matter and can help, networks are a sure-fire way to make your own progress in life.

Flexible Nation

Finally, a word on flexibility: because this is Britain’s killer app – not as critics argue, its achilles heel. In my book The Nowhere Office, I predicted that hybrid work and flexible work would become embedded in a post-pandemic workplace and despite the headlines and the “Return To Office” push, it is clear this analysis was correct. Post pandemic, the world has become more flexible and people have taken much more control over their working lives.

The position of women in the workplace is especially significant. Nobel laureate, Claudia Goldin, writes expressly about the negative impact on women’s careers when they have children – what she calls “the motherhood penalty”.

The difficulties of women having to work through the pandemic while simultaneously organising their children’s schooling were almost too painful to remember. Women have been at the forefront of net gains in the new post-pandemic flexibility: almost three-quarters of UK employers now offer hybrid or remote work.

It is worth remembering that the story of flexible work is, and always has been, a Labour one, even though the final push came, thanks to post pandemic pressure, with the Conservative-led Flexible Working Bill introduced in 2024.

Cast back to Tony Blair’s government which first coined the term “work-life balance” in Parliament in 2000, when Dame Margaret Hodge, then an MP, stood up in the Commons and said that “achieving a good balance between work and the rest of our lives is central to the agenda of the government, and to that of the British public”.

A report in 2023 found that 71% of workers think that a flexible working pattern “is important to them”. Labour should be using the 2025 anniversary of introducing work-life balance into Hansard as a springboard to demonstrate how it led before and will lead again on core issues such as where and when we work. This includes what I call a “presenteeism premium” to acknowledge that those who cannot work flexibly should be compensated given how much emphasis people place on freedom and mobility in how they live and work.

Labour politicians have to come out from behind their policy frameworks in 2025 and talk openly and humanely about work. They have to listen and learn: to upgrade their understanding of what work means. That’s hard – but it will pay off.

Julia Hobsbawm hosts The Nowhere Office podcast. Her latest book is Working Assumptions: What We Thought About Work Before Covid and Generative AI – and What We Know Now. She is the founder of Workathon which advises governments and corporations how to improve their work strategy and practice