Early one morning,

Just as the sun was rising,

I heard a young maid sing in the valley below.

“Oh, don’t deceive me,

Oh, never leave me,

How could you use a poor maiden so?”

The news from Ukraine kept many other stories off the airwaves and out of the papers last week. One that most people missed was the annual conference of the National Farmers’ Union (NFU).

Even in the quietest of times, this would not normally have been a front-page story or the lead item on BBC News at Ten. But these days farmers are angry and they feel used. And they are right.

The delivery may have been different, but the words used by Minette Batters, the newly re-elected president of the NFU, recalled TUC firebrands of the Thatcher era. The Boris Johnson administration, she said, was responsible for “an utter disgrace and a disaster”, with “contradictory government policies” and a “poorly designed change to immigration policy” showing it lacked a “strategy and a clear vision for what we expect from British farming”.

She described farming’s relationship with Defra – whose minister, George Eustice, had an uncomfortable time in their Q&A session – as “fraught”, and asked him to produce “a plan that pre-empts crises rather than repeatedly running into them”. This was powerful stuff.

Like the poor maiden in the old folk song, the farming industry seems to have woken up to the fact that it has been used and abandoned by what it thought was its one true love.

It is not just that Brexit turned out to be not quite the bed of roses it was promised – it is far, far worse. Its whole future is now under threat in a way that seemed impossible just a few short years ago, and the threats come not from hunt saboteurs or vegans, not even from urban types who just “don’t understand” the rural way of life, but from its former sweetheart, the Conservative Party.

Agriculture in the UK, like in many other countries, has an influence out of all proportion to its real worth. In a way, that is natural enough. Farming is, after all, about the very country itself, green fields, wide-open spaces, fresh air and beautiful views; farmers preside over vast areas of the country.

But economically they are virtually irrelevant. Agriculture accounts for just over 0.5% of the British economy and it continues to shrink as a percentage as other parts of the economy grow more quickly. To put that in context, manufacturing accounts for over 17% of the UK economy, 34 times bigger than farming and the service sector makes up 70% of the economy, making it 140 times more important.

But until now the farming sector has had not only the huge advantage of being able to portray itself as the custodian of the nation’s land, but it has also enjoyed the benefits of being one of the Conservative Party’s most loyal supporters. In many parts of the UK’s countryside, a pig with a blue rosette would win an election.

It also explains why 60% of farmers voted for Brexit. They are natural Conservatives, many of their MPs are from the Brexit-supporting right wing of the party and they were greedy. Farmers were told that Brexit would mean the same access to the same markets and even more free taxpayers’ money to support them, and they fell for it.

As with the fishing industry, the Brexit campaign pretended to champion the farmers’ cause against Brussels, sought endless photo opportunities in farms and fields and then the second the vote was won dumped them. But it is only now that the full scale of that betrayal is becoming clear.

The industry has four major worries about the government’s policies. They are trade deals, standards, immigration and the new subsidies regime.

The government’s head of trade deal negotiation was until recently Liz Truss. The former Remain supporter is now foreign secretary, bringing her penchant for wrapping herself in a flag at every inappropriate photo opportunity to a whole new audience. But while she was in charge of negotiating post-Brexit trade deals, she had one overriding impulse.

That the government must be seen to sign trade deals. Good, bad or indifferent, the details don’t matter. Brexit will be seen to be working so long as the government can be seen to have signed a trade deal.

Hardly surprising, therefore, that her interlocutors saw her coming a mile off.

Truss’s trade deals with Australia and New Zealand were negotiated in haste, and so badly that they gave the farming sector’s antipodean competitors almost everything they could have dreamed of.

Specifically, the Australian deal allows beef, lamb, dairy products and sugar almost unlimited tariff- and quota-free access to the UK market within the next five to eight years. There is no way that domestic producers can compete against the much larger and cheaper Australian farms. The idea that Britain’s producers will benefit from access to the Australian and New Zealand food market is a joke, they neither need nor want more expensive produce from the other side of the world; they are food-exporting economies.

The farming industry also fears these deals set an awful precedent for any future trade negotiations with Canada, the US, and many other countries. The government seems more than willing to do exactly the opposite of what it has always promised. Allow cheaper foreign food to undercut its own domestic industry. As Batters told the conference, the government’s own assessment is that the Australian deal alone would cut British beef production by 3% and lamb by 5%. British farmers cannot afford many more triumphs like that. “I’d be much happier as an Australian farmer than a British one,” she said. Those trade deals are also, the industry fears, a Trojan horse for declining standards. While British farmers are being forced, quite rightly, to maintain high standards, they are facing new competition from overseas producers who are not maintaining those standards at all. This gives the foreign food producers a huge price advantage and means that domestic production is being forced to fight with one hand tied behind its back. What it will mean for the next tranche of negotiations with the US and other huge food exporters is terrifying the industry. America allows hormone-injected beef and chlorine-washed chicken, both of which are cheaper than British production methods, but when we were in the EU they were banned.

Allowing them into the UK would not just undercut domestic producers again, but would also be a serious threat to UK exports to the EU, as food producers would have to prove that their products had not been “polluted” by imports.

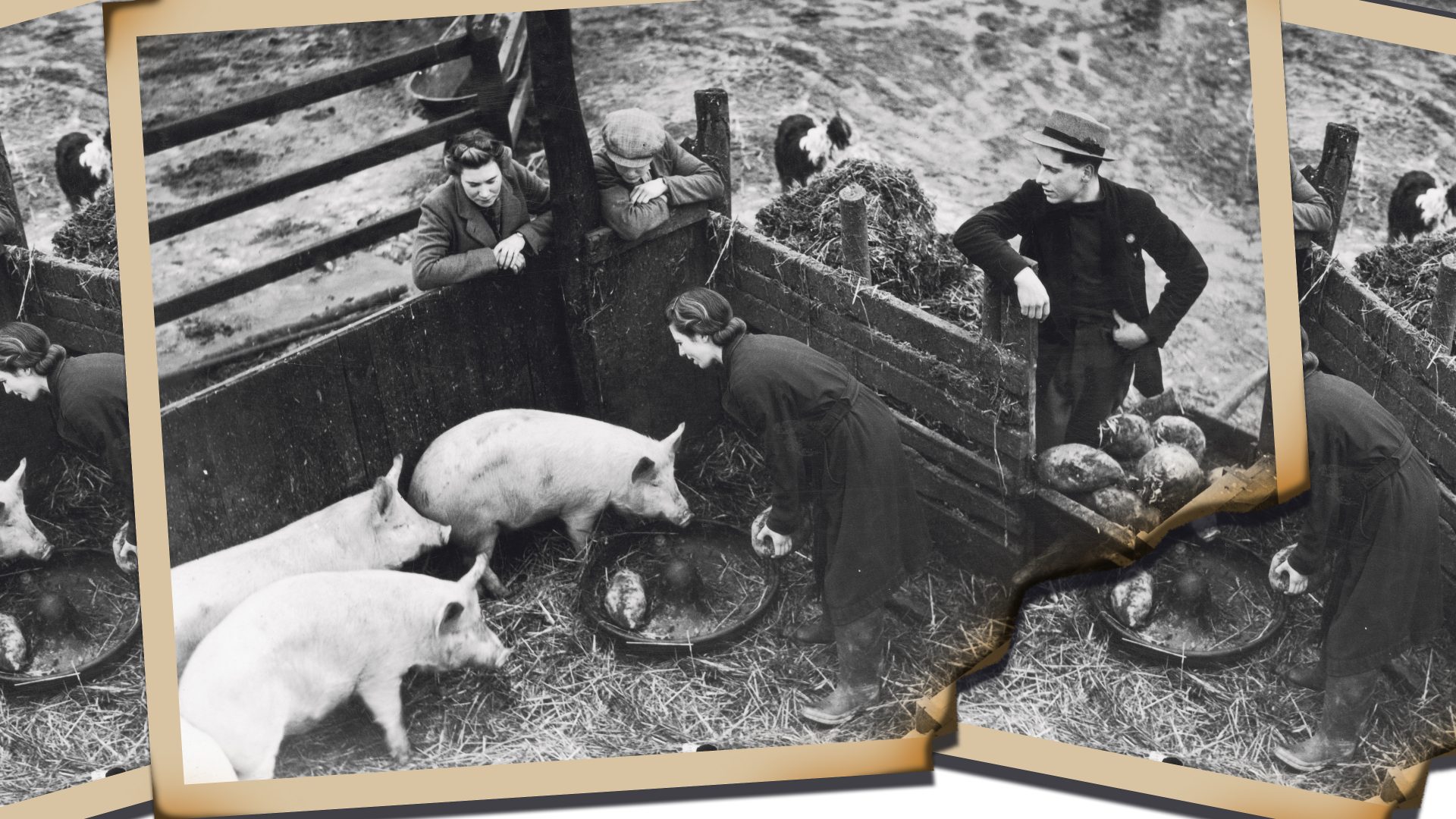

The farming industry has also been deceived by the government over immigration, and especially migrant workers. The pig industry is suffering most from the subsequent labour shortage, and Batters spoke of “heartbreaking” letters she had received from members. “The pain and emotional anger from those pig farmers who feel utterly let down and abandoned is palpable,” she said.

Forty thousand pigs have had to be culled and their carcasses destroyed, while another 200,000 animals are stuck on farms and can’t be processed because of a dire shortage of workers in abattoirs. The horticultural sector could be next on the list, as it needs pickers and processors and normally relies on migrant labour to do the work.

New inspections at UK ports will also mean they will need far more vets to do the work; there are nowhere near enough UK-trained staff.

Finally, the industry’s amour propre has been seriously damaged by the government’s new policy on subsidies. It may be hard to feel sorry for an industry that voted for Brexit on the promise of even more subsidies from taxpayers – it was not the noblest of motives – but the government has taken full advantage of the farmers’ naivety.

The idea that once the Treasury was responsible for agricultural subsidies it wasn’t going to take one look at the industry, lick its lips and decide how best to save a few billion pounds a year was very stupid. Unfortunately, the government’s new subsidy regime seems to have gone beyond just taking advantage of that stupidity to save money and has now moved on to introducing a scheme that doesn’t really work.

Farmers fear that the new subsidies regime won’t allow them to make a profit and yet also has huge targets for setting land aside for environmental reasons. Paying farmers not to produce food and bankrupting those who still do is not going to enhance domestic food production.

But leaving aside all the technical reasons for the farming industry’s dismay – trade deals, standards, workers and subsidies – the industry’s real complaint is that the government has abandoned it.

The government wants trade deals at any price and immigration controls no matter what the cost. If that means lower food standards, unpicked crops, unfair competition for its own industries, so be it. Farmers are being told to like it or lump it, something they have never experienced before.

The government treated the farming industry just like that “poor maiden”, it was deceived, used and abandoned. It is left holding the baby and has been kicked out into the cold.

And worst of all, no one is listening.