You know that productivity has been a long-running issue for the British economy when, in a keynote speech, the current chancellor quotes a former prime minister from the 1960s, who was himself referring to the works of Jonathan Swift (1667-1745).

At his Mais lecture in late February, staged in the halcyon days before Non-Dom scandals and Partygate fines, Rishi Sunak referenced Harold Wilson’s celebrated 1963 speech about the white heat of technology. In that speech, Wilson quoted Swift: “Whoever could make two ears of corn, or two blades of grass, to grow upon a spot of ground where only one grew before, would deserve better of mankind, and do more essential service to his country, than the whole race of politicians put together.”

This doesn’t really say much about the quality of our politicians, because almost 60 years later the UK economy is still trying to grow two ears of corn where previously only one grew, and failing miserably.

This really matters, because without productivity increases we cannot become wealthier, and we cannot raise the taxes necessary to pay for everything from defence to the NHS.

Productivity is basically about how much you make and what you need to make it. Over time economies, firms and people get better at making more with less; shorter hours, less energy, fewer raw materials. It is all around us and has been going on for ever. Just think about how many hand looms were replaced by one steam-powered mill and how many typing pools have disappeared and been replaced with laptops. You get the idea.

But while the UK led the world in the Industrial Revolution by massively increasing productivity, it long ago fell behind its rivals and shows little sign of catching up.

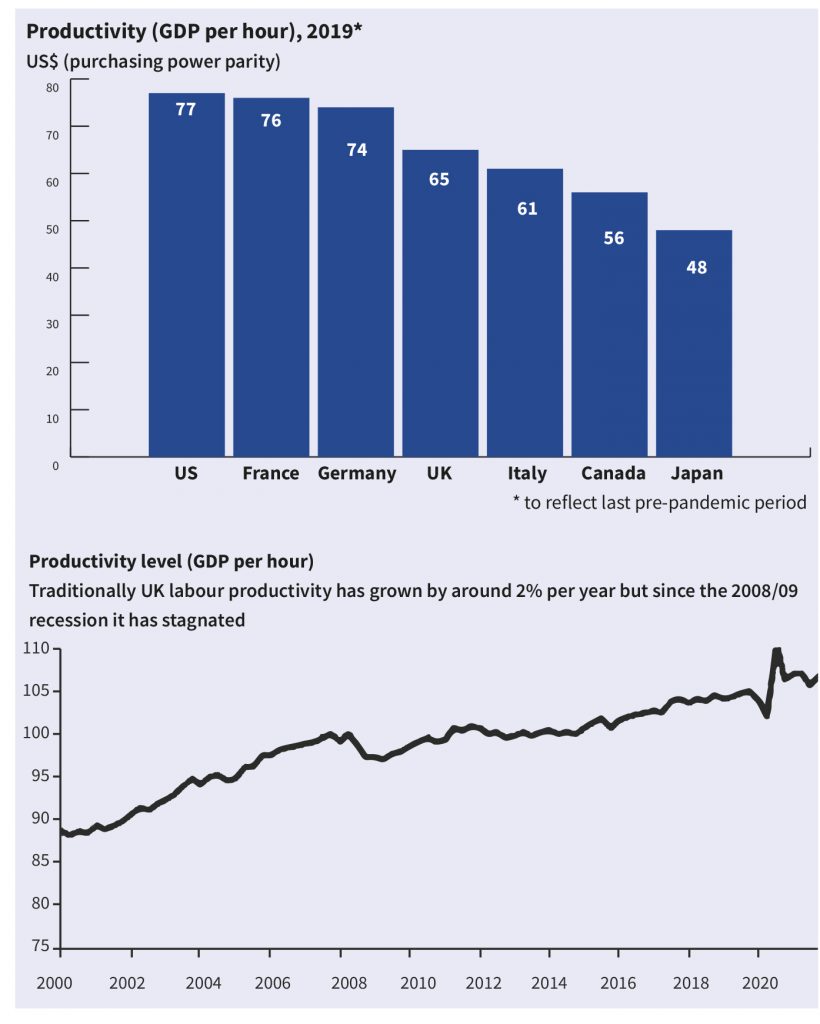

Productivity in the US is more than 20% higher than here; in France it is about 20% higher and in Germany at least 10% higher, and probably much more. Or to put it another way, the average French or American worker could take every Friday off and still produce more than a British person working a five-day week. Also, the figures are getting worse. Since the credit crunch, improvements in productivity have slowed dramatically.

Between 1997 and 2007, the UK’s output per hour rose at the second-fastest rate in the G7 at 1.9% per annum, but between 2009 and 2019 it was the second slowest at 0.7% pa.

The credit crunch had a devastating effect on the increase in productivity, not least because banks stopped lending. Other countries suffered as a result, but not by as much, and so the UK’s attempt to become as productive as its rivals is failing and failing badly.

Sunak was, therefore, once again struggling with the eternal worry of British chancellors: “Why is the UK economy so unproductive and what can I do to fix it?”

The answer to the first part of the question is fairly simple, but the answer to the second part is neither simple, nor easy, nor cheap.

Successive chancellors from both sides of the political spectrum have struggled to find the solution, mainly because it would involve deeply unpopular and radical policies that they are unwilling to implement.

Although there is much debate about which is the most important factor, the UK’s lamentable productivity is down to three main faults.

They are low investment, bad education and training and, finally, bad management.

LOW INVESTMENT

Low investment takes many forms and has been one of the biggest weaknesses of the British economy for as long as anyone can remember. British companies invest about 10% of GDP in new factories, machinery, computers, distribution networks, R&D and all the rest. In Germany, France and the US the figure is 13%, which does not sound like a huge gap until you recognise that that is 30% more than British companies each year and every year.

On top of that, the British government itself is a poor investor in infrastructure and research. Every traffic jam, slow internet speed, train cancellation and every crowded lorry park at a UK port is an inefficiency that could be removed by more spending and better infrastructure. The government is now trying to increase investment but only to the G7 average; the UK has fallen well below that level for decades and it shows.

Even the housing market has a negative pull on productivity. When your house is your biggest asset and when the difference between house prices across the country is so huge, the best people do not move to the best jobs and labour mobility dies. Building more and cheaper homes would boost the UK’s productivity.

BAD TRAINING AND EDUCATION

Not only do workers in more productive countries have more investment to work with, which means newer factories, better machinery and clearer roads, they are also better trained and educated. That means they can use that investment better. Shamefully, a lot of the UK’s problems are down to the fact that a third of 16-year-olds leave school with poor maths and literacy skills, and it is very difficult to employ them, let alone find them well-paid work.

Also, as the OECD reported in 2017, the rate of vocational training is lower than our rivals and the level of apprenticeships is also weak by international standards. Only 24% of students opt to become an apprentice, whereas in Germany the figure is 41%.

The UK’s apprenticeship system was supposed to have been reformed in 2017 with the introduction of a levy to help pay for the training. It has been a disaster. The government has sat on its hands and watched apprenticeship numbers fall by a fifth as a result.

The UK labour force is, therefore, low skilled. Some 22% of jobs only need lower-level qualifications, and even those students who do manage to get training are doing the wrong kind of training. Only 33% of jobs need a university degree, yet 50% of school leavers go to university.

BAD MANAGERS

Finally, whisper it if you dare, but the managers in British companies are generally bad.

Part of the problem is down to the number of family-run firms in the UK, firms where the owner’s child gets a place on the board after working their way up from the shop floor in just six months. This is known as the Tokyo Olympics problem. Would you have picked the British squad for last year’s Tokyo Olympics by just selecting the grandchildren of the team that went to Tokyo in 1964? Obviously not, but that is what you are doing when you appoint your children to the board. In Germany, where there are many highly successful family-owned firms, they are far more likely to be family-owned but professionally run. But even taking that into account, British managers tend to be less well qualified, trained, and experienced than their counterparts in other countries.

In Germany a degree in Latin would qualify you to teach Latin, not to run a car plant. Managers I meet in French and German factories often have several directly relevant degrees, an MBA and speak three languages fluently.

What makes this even more worrying is that the productive firms that invest a lot and have good managers are often foreign-owned. Without investment from abroad, the UK’s productivity record would be far worse and Brexit has damaged that investment, perhaps permanently.

THE SOLUTION

In his lecture the chancellor came up with some good ideas; lifelong learning, finding ways to make companies invest more and, to be fair, the government is increasing its own investment levels. But even so, the UK is decades behind France, America and Germany.

What the country really needs is a complete overhaul of its education system, which fails millions every year. That would mean spending billions a year on improving schools, providing more and better vocational learning and reversing the disastrous reforms of the apprenticeship system.

The UK also needs to move from current consumption to long-term investment. That means ending the short-term dividends-driven agenda of British firms and instead making them spend billions a year more on investment and training. The government would have to do the same for infrastructure and housing. A sustained period of massive, council-run house building is the obvious – but expensive and controversial – answer.

But that also means higher taxes, or at least fewer tax cuts.

Finally, you really need to find a way of ending the preponderance of family-run firms in the UK. You would also need to enhance professional standards for managers and end huge payouts for lacklustre results.

None of this will win votes in the short term, which is why chancellors have been struggling with the problem for decades. They know the answers, but none has had the guts, the foresight, or the money to fix the problem.

In the long term, reforms would make the UK more productive and when workers make more they get paid more, the country gets richer, and the government has more revenue.

But at the current rate, the Mais lecture in 2082 will be given by a chancellor bemoaning the terrible productivity of the UK’s economy.

Jonty Bloom is a freelance journalist specialising in business, financial and European issues.