Before Brexit there was Cool Britannia, and at its heart grinned the thoroughly Anglo-Saxon Damien Hirst. “There was in his face something ruddy and heavy, typically English, which made him look like a rank-and-file Arsenal supporter,” writes the French novelist Michel Houellebecq in The Map and The Territory (Hirst is from Leeds.)

The confidence of British culture in the decade before the millennium enhanced national delusions, chipping away at middle-class reverence for continental civilisation. Suddenly you didn’t need to sit through films with subtitles or read Italo Calvino to feel sophisticated. Instead you could enjoy Hirst’s art and that of the generation he led. So the spectacular artistic fall of Damien Hirst may say something about Britain, its self-image and relationship with a wider European culture. Who do we think we are, if our coolest, wealthiest, most famous artist, who has always been viewed as quintessentially British, is actually talentless?

Few artists have ever been so cruelly undone by time as our Damien. He’s still obscenely rich, protected from wider cycles of taste by the luxury art market that means he just needs to sell to a few ignorant billionaires who go for names and celebrity rather than quality. And he’s still genuinely famous, in a world where even the most distinguished artists usually have little purchase on popular culture. Just look for news about them on TV – Frank Auerwho?

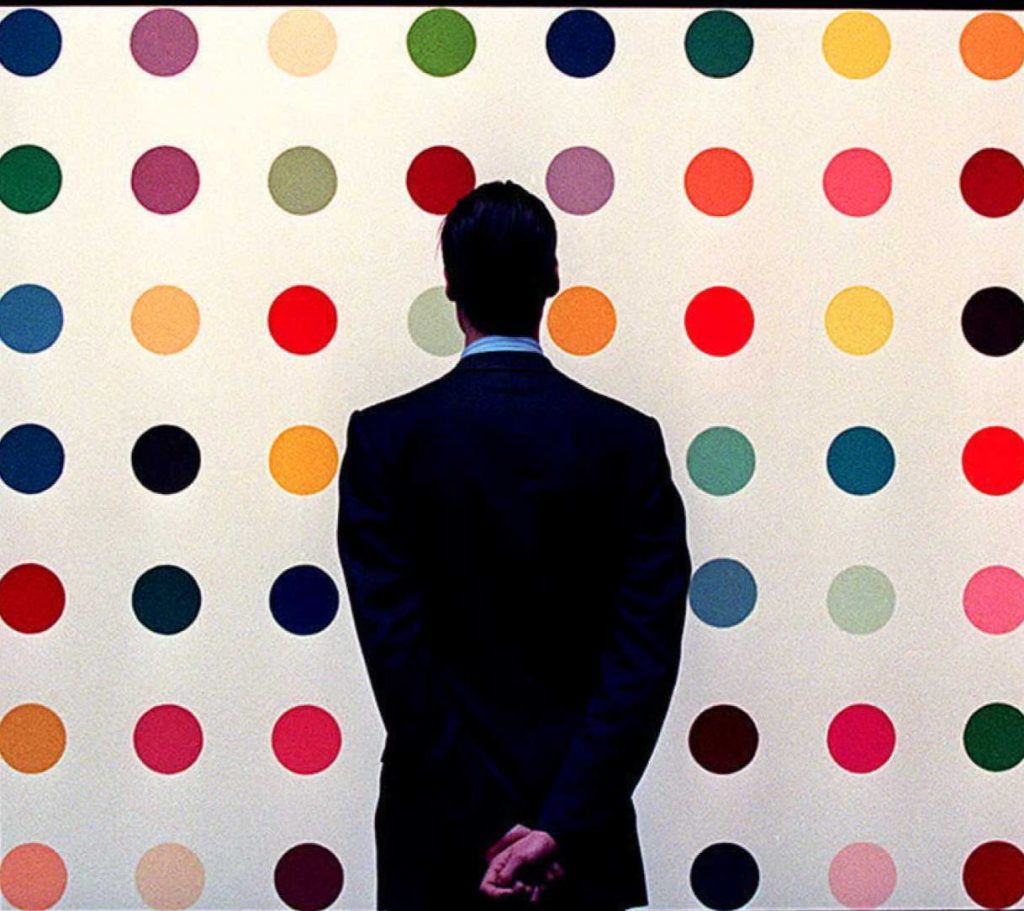

auction house, September 2008. Photo: Shaun Curry/AFP/Getty

But Hirst has lost his claim to anyone’s genuine love or respect in a fall so comprehensive it may be a one-off in the history of art. It isn’t merely that his work has been in a more or less continual nosedive since the start of this century, when he shifted from putting dead animals in vitrines to making outsized replicas of science toys before taking to his shed with easel and brushes to prove that he absolutely cannot paint.

Artists who have a brilliant early career followed by more ordinary maturity are familiar enough: Renoir, De Chirico, Dalí, Warhol and Hockney, to name but a few. Some would claim that even Picasso never again matched his Cubist period. It doesn’t usually undermine our admiration for their early masterpieces.

With Hirst something truly strange has happened. After 26 years of betraying his original promise, ever since he unveiled his ugly, derivative, anatomical colossus Hymn in 1999, his cynical present has infected his dazzling past. His early works have come to seem banal, pointless, even fraudulent. It is no longer possible to take them seriously.

1000 Years, his 1990 installation in which flies spend their entire lifecycle inside a divided glass tank where they can choose to pass from the “safe” half into a more tempting and dangerous chamber that contains a tasty rotting cow’s head and a lethal Insect-O-Cutor, once seemed a genuinely tragicomic artistic device, a carnival of little deaths to make us foresee our own. Now it just looks silly and bathetic.

So do the animals preserved in vitrines, even the tiger shark, especially the tiger shark since it shrivelled so quickly to resemble a centuries-old specimen instead of the live monster swimming towards you that scared and thrilled visitors to the Saatchi Gallery in the early 1990s.

It doesn’t help that Hirst, as an investigation by the Guardian has revealed, appears to have concocted several new animal vitrines in recent years to which he gave 1990s dates – literally corrupting his own artistic biography. This is the infected icing on an already mouldering cake. It’s a genuine mystery how works that once seemed so fresh have gone so stale.

It seems that you can be too much of your time. When I walked into the Saatchi Gallery and saw the grinning toothy maw of The Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living refracted through blue formaldehyde back in 1992, I felt for the first time I was beholding a truly contemporary work of British art. As a student I’d never encountered any British art that seemed new, shocking, edgy and truthful in this way: while novels by Martin Amis or Ian McEwan seemed to have the nicotine taste of their absolute moment, what “contemporary” British art I’d seen seemed irrelevant and vague. Now this: an actual f***ing shark in an art gallery! As Hirst may have put it in his head.

But it was clever, not profound, though part of that cleverness was at least raising the possibility of profundity. What’s more real and biting to think about than death? In making mortality his relentless theme, the young Hirst outwitted other pop conceptualists like Jeff Koons.

To enjoy Koons is to delight in an elaborate mimicry of kitsch, to appreciate an ironic replication of pop cultural consumerist banality that may be either brainless celebration or razor-sharp satire, or both. This is art about art. But Hirst offered art about life – or at least about death.

His methods may have been the art school cliches of the Duchampian readymade and the conceptual movement, but his content reached out far beyond such academic fashions to echo Hans Holbein’s molten skull spreading across the surface of The Ambassadors, or Dutch Vanitas still-life paintings, or the medieval danse macabre. Death, “the distinguished thing” as Henry James called it, seemed to compel and transfix the young Hirst.

The reason his art has been exposed as empty and sterile is that he wasn’t driven by fear or obsession at all. No biographical secret, no psychology underlay his interest in pickling animals. It was a game with art history – a conscious choice to appropriate the mortal themes of great art.

This became obvious to many as soon as Hirst unveiled the cynical Hymn, but I was a diehard fan, trying to see something in him years after he became a mega-rich artist of the deal. I only saw the truth when I interviewed him by Zoom during the pandemic.

We had a decent conversation, he was friendly and easy to get on with. But he did not seem like an artist at all. Artists are driven and mysterious. He is not. He’s a bloke you meet at the pub, or in this case his Regent’s Park mansion.

I now know why I was so slow to accept this fundamental absence of an artist in him. It was because, if Hirst is rubbish, and he is, it raises rather awkward questions about the rest of British art, past and present.

Britain has always been an outlier in the story of European art. It contributed almost nothing visual to the Renaissance or the early 20th-century golden age of Modernism. In both those dazzling periods of European culture, our strengths were instead literary: Shakespeare is our Titian, WH Auden our Picasso. The English Reformation literally smashed statues and paintings in churches and destroyed demand for English artistic specialities like alabaster carving.

The art void was filled by continental artists, from the German Holbein at the court of Henry VIII to Antwerp’s Van Dyck in the Baroque age. There’s no homegrown British answer to Dürer, Van Eyck, Botticelli, Rembrandt, Velázquez – and so many more European geniuses. Only in the 18th century does a British school start to emerge. Yet it has rarely seemed significant beyond Britain’s shores, give or take Turner and Constable. It takes a real Little Englander to pretend the likes of Henry Moore rival their continental contemporaries like Magritte, Mondrian, Boccioni, Malevich, Dix, Höch, Ernst. Just as in the Renaissance and Baroque ages, modern art seemed to be something that came from elsewhere.

Then Damien Hirst turned up, chainsaw in hand, to butcher British art into world history. There had never before been a British artist who looked like the absolute, electric, cutting edge of modern art. Even in the 1960s, British Pop Art had been comforting and granny-chic with its Peter Blake collages, compared with the amphetamine dread of Warhol’s Factory. Hirst brought the Factory’s walk on the wild side to London. That shark. So vulgar, so crass, so bloody brilliant.

Now we can’t believe he ever had us fooled, but what does that say about British art since the 1990s? It has entered one of its very worst periods; dull, complacent and repetitive. Hirst didn’t just make money for himself. He opened British mainstream culture to the very idea of “modern art”. It used to be conventional, even fashionable, for middle-class Britons to despise the antics of Those Modern Artists, from Yoko Ono ruining John Lennon with her Fluxus posing to Carl Andre selling a pile of bricks to the Tate.

That was Before Hirst. Today, After Hirst, no middle-class person would dare question the Brilliance and Urgency of contemporary art, especially contemporary British art, even though none of it has actually stuck in anyone’s mind for quite some time now. So the zombie Turner Prize shuffles on, without shocking or inspiring anyone, and a certain kind of idiot still pretends there’s stuff worth seeing at the hideous Frieze Art Fair. But the jig is up for British art, and it was the moment Hirst stopped fooling anyone with eyes and heart.

The worst thing he and his generation of Young British Artists did was to impose on British visual culture a binary, polemical division. Figurative painting, which in reality had been the chosen territory of such incisive geniuses as Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud, was caricatured as stale, passeist, irrelevant. Only conceptualism, the readymade and photographic and video media have anything to say about life now, according to this ideology.

The Turner Prize still pretends it’s inherently daring and avant garde to put a doily on a car, as if anyone on earth is troubled, stunned or even mildly diverted by such fourth-hand retreads of the controversies Hirst and co once provoked. At least you can’t accuse Hirst of being a goody-two-shoes. His use of dead animals was amoral and aesthetic. There was danger in it. Now, British art is full of moral and political virtue that muffles any chance of it being outrageous.

How I wish Hirst, who will be 60 this year, had kept his energy like Germany’s Anselm Kiefer, who will be 80. A couple of years ago I watched Kiefer supervise a forklift dumping massive slabs of smashed concrete in a London gallery. This was originally an entire floor of his Paris studio, he explained: he had wondered what would happen if he cut around it and let it fall.

In the same exhibition he showed vast paintings of black sunflowers and eerie riverbanks amid a delirious installation rusting with history and bulging with myth. Kiefer is everything Hirst has turned out not to be: a true artist whose imagination keeps renewing itself and who can make you think and feel with both conceptual daring and painterly prowess.

That’s not so unusual in German art. Germany has never polarised the cool and uncool in art in the shallow, thin way Hirst has bequeathed the British. Kiefer was guided by Joseph Beuys, whose found materials and performances invade the real world with history’s ghosts. He has always mixed painting with Beuys-like actions and installations. His paintings themselves are three-dimensional, so heavily daubed they spread out into your own space – often with boots or vegetation or even easels stuck to them. This is, I suspect, everything Hirst once wanted to be.

Kiefer is part of a far deeper, older, more nuanced artistic tradition than Hirst. After all, Germany nurtured great Renaissance artists like Cranach and Grunewald, whose visceral genius is still very much alive in modern German art from Dix to Baselitz and beyond. From this perspective, the obsessive British contrast between concept and canvas looks scratchily immature. The same can be said for other European nations: you can put Picasso in the Prado and instantly see his complex affinities with Velázquez and Goya.

Britain likes to think its cultural heritage and future are insular, but that has never been the case. Damien Hirst fed the worst fantasies of the British by making us appear an artistic island with a guttural vision all its own. But our culture and heritage only make sense as part of our continent. Erect a cultural border and you keep out the flow that had Shakespeare dramatising the lives of Italian merchants, TS Eliot quoting Baudelaire and paraphrasing Dante, the National Gallery amassing a great collection of Europe’s art. Now where are we?

This year there will be Kiefer exhibitions in Britain to mark his big birthday. They will satisfy the parts no contemporary British art can, least of all Hirst. We are back in the age of Holbein, getting our great art from Europe.

Jonathan Jones writes on art for the Guardian and was on the jury for the 2009 Turner prize