If ever there was a writer who seemed to be hewn from the very rock of

America, it was John Steinbeck. The landscape itself flowed through his pen and the deep understanding he had of its people fizzed from every page. Steinbeck, to his last fibre, was an American writer of American stories.

Yet the Nobel prize-winning author, who was born 120 years ago this week,

wanted no part of the flag-wavin’, gun-totin’ version of his country that

has been shouting particularly loudly in recent years. Instead, he wrote with

an unshakable faith in the original vision and spirit of the US, a genuine

meritocracy of equal opportunity that raised everyone up, not just a few.

Nobody captured better the lives of the outsider and the downtrodden in 20th-century America, and his native California in particular, than John

Steinbeck. In books like Of Mice and Men, The Grapes of Wrath – which won

the Pulitzer prize in 1940 – and East of Eden, Steinbeck documented the failure of the American dream through its victims, those cast aside, affording

ordinary people a dignity and humanity stripped from them by the particularly rampant form of capitalism that hypnotised the US during the 20th century.

Writing and writers don’t come more American than this, yet his outlook was far from parochial. Indeed, John Steinbeck was a Europhile.

He first crossed the Atlantic as a war correspondent for the New York Herald Tribune, witnessing commando raids in the Mediterranean, helping to round up prisoners of war with a Thompson submachine gun and being wounded

by shrapnel. A tour of the Soviet Union followed in 1947 in the company of

photographer Robert Capa, resulting in the collaborative travelogue A Russian Journal the following year.

In the spring of 1952, having just completed East of Eden, Steinbeck and

his wife, Elaine, undertook a comprehensive tour of Europe, arriving in Spain via Algiers, visiting Madrid, then on to Paris, from where he drove to Milan, Florence, Venice and Rome. London was next, where among other things the Steinbecks saw John Gielgud in Much Ado About Nothing, before heading back to New York via Ireland.

He returned two years later to spend a few months living in Paris, where he

wrote a number of opinion pieces for French newspapers – and conceived

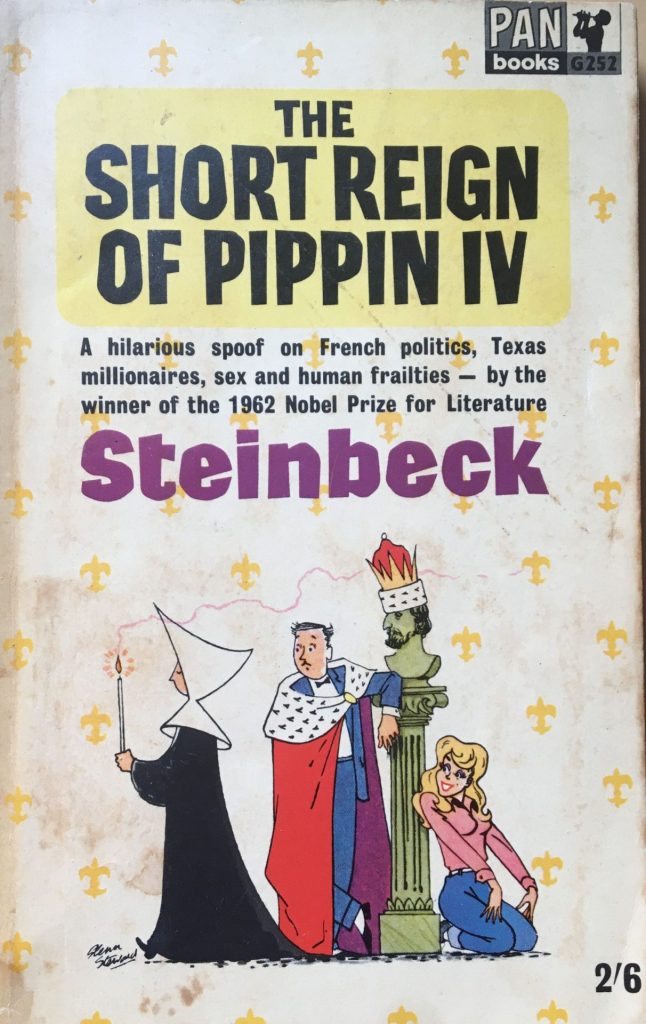

the idea for what is unquestionably the most unusual of his 16 novels, 1957’s

The Short Reign of Pippin IV.

By 1956, Steinbeck had grown disillusioned with the writing business. While his books always sold in great quantities, his compassion for the common man made him a target for the more traditionally minded America and he was never truly accepted into the US literary firmament.

That year, when the Democrat Adlai Stevenson was up against the incumbent Dwight D. Eisenhower, Steinbeck was due to cover the parties’

national conventions as well as writing speeches for Stevenson. The task

wasn’t filling him with gleeful excitement: his opinion of US journalism had rarely been lower.

He was similarly exasperated with literature. Reacting to an interview with the newly crowned Nobel laureate William Faulkner, he lamented to a friend, “when those old writing boys get together and start talking about The Artist, meaning themselves, it makes me want to leave the profession”.

Steinbeck sought escape in the form of a comic novel about contemporary

France.

After the establishment of the Fourth Republic in 1946, France was enduring a period of political upheaval in which a succession of flimsy coalition governments formed and fell. Having witnessed this firsthand in Paris, Steinbeck found himself imagining what might happen if the French sought to break this stifling cycle by re-establishing the monarchy.

Before long this thought had turned into The Short Reign of Pippin IV.

With France locked in political stalemate, the suggestion that the nation renege on the principle underpinning the 1789 revolution is met with surprising unity across the spectrum. And what a spectrum Steinbeck devises, starting on the right with the Conservative Radicals and the Radical Conservatives, through a centre occupied by Christian Atheists and Christian Christians, to the Communists who are of course split into four factions. Even the latter are in favour of a new monarchy on the grounds that a king would be something to unite against.

They find themselves on the same side as the royalists, with a representative of the Merovingian dynasty marking the selection of the new king by lamenting how, “In the days of my ancestors these matters of succession were handled in a nobler manner – with poison, poniard, or the quick and merciful hands of a strangler. Now we have surrendered to the ballot.”

The monarch they settle upon is Pippin Héristal, middle-aged amateur astronomer and a direct descendant of Charlemagne. Pippin turns out to be

far from the patsy the politicians need him to be, seeking instead to impose

his own progressive liberal ideology on to the nation. At first, Pippin is a

roaring success: the US and USSR fall over themselves to bestow loans, tourism thrives like never before and the economy flourishes. It can’t last, of

course, and Pippin IV’s reign is destined to be short.

“It is the tendency of human beings to distrust good fortune,” writes Steinbeck. “In evil times we are too busy protecting ourselves. We are equipped for this. The one thing our species is helpless against is good fortune. It first puzzles, then frightens, then angers, then finally destroys us.”

Pippin is not Steinbeck’s greatest work, but this smart, pacy and very funny book still deserves to be better known. The author’s love of France is obvious. The jokes have aged surprisingly well and the political satire never feels as if it’s coming from a different age. Politicians have, after all, always been conniving and self-serving.

The characters are brilliantly drawn, from Pippin’s antique-dealing Uncle Charles, who specialises in selling paintings of dubious provenance to rich tourists, to his wife’s old schoolfriend, Suzanne, who spent two decades as a dancer at the Folies Bergères then took holy orders purely because her feet were killing her and she needed a long sit down.

For a man disillusioned by journalism, literature and politics – Adlai Stevenson, whom Steinbeck regarded as having unimpeachable integrity and on whom Pippin is loosely based, lost the 1956 election to Eisenhower – this is a joyous, playful satire packed with some terrific jokes that still hit home today.

“I can’t remember when John seemed to be having so much fun with a book,” Elaine Steinbeck told a friend as she heard chuckling and typing from behind the door of her husband’s study. When he sent the manuscript to his agent, Elizabeth Otis, Steinbeck attached a note that read, “I find I completely believe in it. Hope you get a few laughs out of it. It certainly shows very little mercy to anyone. As a matter of fact, I rather think the

French will like it. It is the Americans who won’t, but then the Americans I

am afraid have very little humour.”

Reviews were generally positive and the book sold well, yet today The Short

Reign of Pippin IV is all but forgotten outside the world of the Steinbeck

completist. Revisiting the story, however, reveals distinct contemporary resonances within its pages, and not just for the French.

“I did not ask to be king but I am king and I find this dear, rich, productive France torn by selfish factions, fleeced by greedy promoters, deceived by parties,” complains Pippin. “I find there are 600 ways of avoiding taxes if you are rich enough and 65 methods of raising rent in controlled-rent areas. The riches of France, which should have some kind of distribution, are gobbled up. Everyone robs everyone until a level is reached where there is nothing left to steal. No new houses are built and the old ones are falling to pieces. And on this favoured land the maggots are feeding.”

The Short Reign of Pippin IV by John Steinbeck is available from Penguin

Classics, price £12.99