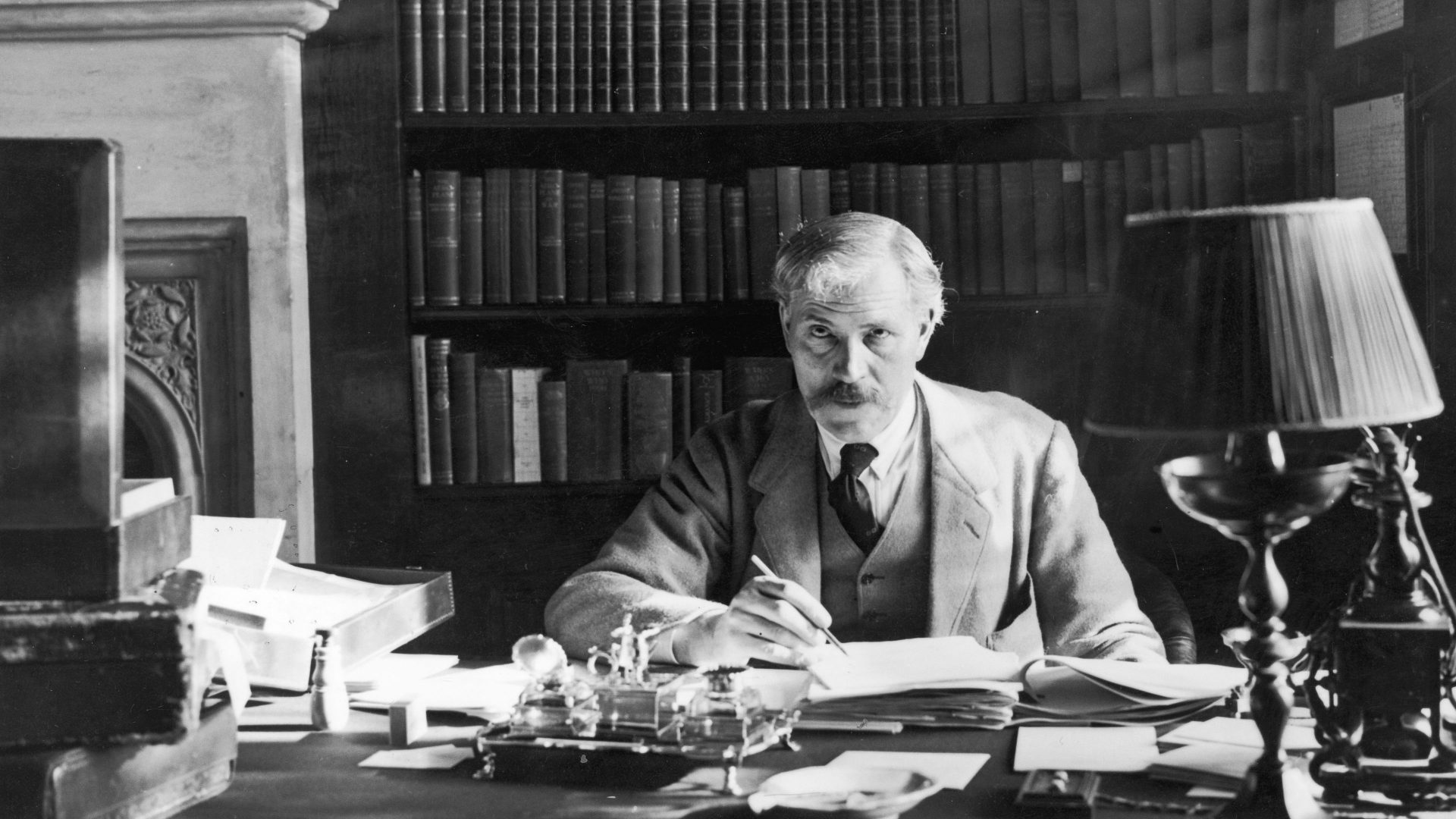

A century ago, the first Labour government was formed on 22 January 1924, when Ramsay MacDonald accepted King George V’s invitation to form a government. MacDonald recorded this moment movingly in his diary:

“Without fuss, the firing of guns, the flying of new flags, the Labour Govt has come in. At noon there was a Privy Council at Buck Pal; the seals of office were handed to us – and there we were Ministers of State… A wonderful country. Now for burdens & worries. Our greatest difficulty will be to get to work. Our purposes need preparation, & during preparation we shall appear to be doing nothing. – and to our own people to be breaking our pledges.”

The expectations of voters and supporters, and the demands for swift delivery, are similar today and provide the frame for the current debate on what Keir Starmer stands for and what difference a Labour government will make.

Since 1931, when Ramsay MacDonald left the party and led a National Government with the Tories, he has been the emblem of treachery. But with Keir Starmer having turned round Labour from its worst election defeat since the thirties and looking poised to form a government, perhaps it’s time to rehabilitate MacDonald. And perhaps Keir Starmer should consider paying at least as much attention to Labour’s first Prime Minister as he does to Tony Blair, the most recent one to win an election.

There are some striking parallels. When Baldwin’s Unionist government was hanging on in office, after its surprise defeat in the 1923 election, MacDonald told Asquith that the government was “a corpse waiting for a coffin to be brought in and for an undertaker to screw it up”. Noting the danger that “This corpse lay in various departments, conducting foreign affairs, labour affairs, watching over delicate and complicated developments in our industries”. It is language that Starmer could use for the Sunak government today.

The Labour Party has a complicated relationship with its own history. Partly, there is simple nostalgia for the rare times when the party has been in government – which is less than a third of its existence. Mainly, and malignly, it’s a search for examples from history that can be used to attack the current leader – after all, betrayal is the mother tongue of the labour movement. Thus, the example of Attlee was used to attack Tony Blair, and in turn Blair is now praised by some on the left to criticise Keir Starmer’s perceived caution, and undoubtedly in due course future leaders will be told “you’re no Starmer!”

MacDonald had to form a minority government – Labour were second place in the 1923 General Election with 191 seats (only slightly fewer than Labour won in their 2019 defeat), but Baldwin’s Conservatives had lost not only 86 seats but also their majority, in a snap election that had been designed to win a mandate for tariffs. Labour governed for only ten months, but that period was decisive for the party and for British politics. This was the moment that Labour supplanted the Liberal Party as the official opposition – and ever since, the party has been the alternative party of government in the UK.

In 1924, Labour had to prove that it could be trusted to govern. Labour’s first MPs had been elected in 1900, and it had never been in government before. MacDonald knew the political, and reputational, bonus that holding office would give to his party and he manoeuvred ruthlessly to become Prime Minister. He persuaded the party’s ruling National Executive Committee to agree that Labour should “at once accept full responsibility for the government without compromising itself in any form of coalition”. He also noted in his own diary that “moderation & honesty were our safety” – a very Starmeresque motto.

Today, after its frolic with Corbynism, Labour has had to prove once more that it can be trusted to govern – though for different reasons. The lesson of ruthlessness has not been lost on Starmer. He may have served in Corbyn’s shadow cabinet, but Starmer has expelled him from the Parliamentary Labour Party and made it impossible for Corbyn to stand again as a Labour candidate. Starmer has shown the same ruthless approach to his shadow cabinet – promoting talent, demoting poor performers, never briefing against them – just acting. In this he is following the famous line of Clement Attlee, Labour’s second PM who, when asked by a minister why he was being sacked replied tersely: “Not up to it!”

MacDonald faced a similar “in tray” of domestic policy challenges to the one that an incoming Starmer government would meet. Class sizes were too high – though in 1924 that meant 60; wages were low; and there was a housing crisis, with no signs of the “homes fit for heroes” promised after the end of the Great War.

In ten turbulent months, it turned out the right answer was to act. Benefits were increased – as were pensions. Agricultural pay was raised and a minimum wage was set. Class sizes were brought down to 40, and local education authorities allowed to raise the school leaving age to 15. Most importantly, “Red Clydesider” John Wheatley introduced a Housing Act, which provided a central government subsidy for council houses.

In an early example of a Public Private Partnership, Wheatley and the housing industry had agreed to an ambitious target of building 2.5m new homes by the end of the twenties. Though this wasn’t delivered, over 500,000 council houses were built in the decade following Wheatley’s legislation. If that figure could be matched by a Starmer government, it would be a revolution in social housing.

The clear lesson for Labour today is – once elected, you must act! Oppositions react, governments determine, and in acting change the frame, the landscape, and the possibilities of politics. The risk is that the message discipline of opposition, which aims to limit gaffes and maintain a reputation for fiscal discipline, is transferred into government, causing paralysis. Tony Blair once said to me: “In opposition you get up every day thinking of what you’re going to say, in government you should get up every day thinking of what you’re going to do.”

Starmer needs to hit the ground running, not dawdling. There are obvious moves he can make in the first 100 days, that would transform what government does and how it is seen. Removing all of the dodgy concrete in schools would cost less than a billion pounds in capital and would be easily found. Ending “hope value” for landowners should start with the Treasury, freeing up government land for transfer to council house building and providing a subsidy that could jump start homebuilding. Abolishing sanctions for Universal Credit wouldn’t cost a penny but would significantly reduce the number of people forced to go to foodbanks.

Government means that good deeds can replace warm words. And the Conservatives have created a massive machine to strengthen executive power. In large swathes of policy, Labour ministers would have delegated power to make change – my advice to Shadow Cabinet members, and their teams, is look at what you can do without bothering with new legislation.

In foreign policy, MacDonald broke new ground too. His government recognised the Soviet Union – the first country in the west to do so. It was also a constitutionally sensitive in the UK, since the Bolsheviks had murdered King George’s cousin Tsar Nicholas during the Russian Revolution. Ramsay MacDonald tactfully informed the monarch that he had signed the treaty as foreign secretary not PM. For McDonald, given the small pool of talent available to him, had put himself in charge of the Foreign Office. He excelled in the task, lowering Franco-German tensions and gaining international respect for helping deliver the Dawes Plan that eased German reparations.

Of course, Keir Starmer can’t be his own foreign secretary, but he has already marked out the spheres of border security, defence and security, and EU relations where he wants to take a lead – tackling people smuggling, strengthening NATO, and reducing friction with the UK’s main trading partner. As with MacDonald’s government, a change of leadership permits a change in relationships.

This is probably the lasting lesson of Labour’s very first term. Governments make a difference when they decide to make one. Power and influence isn’t given, it’s taken. The impact of your government comes from shaping the future, not merely managing the past. And its significance comes not just from the top but also from the team.

John Wheatley left an institutional legacy in housing. (As later Nye Bevan did with the National Health Service.) In Starmer’s government, if they deliver the Green Prosperity Fund with its industrial strategy, warm homes, and a decarbonised nation, that will be the fundamental institutional legacy. It will be omething that shapes the country for the rest of the century.