Here is a scary fact. Among the four frontrunners in the French presidential election, there are two candidates of the far right.

Here is a reassuring prediction. While polls have tightened as the cost of living crisis bites, neither of those candidates – certainly not Éric Zemmour and probably not Marine Le Pen – will enter the Elysée Palace as president later this month.

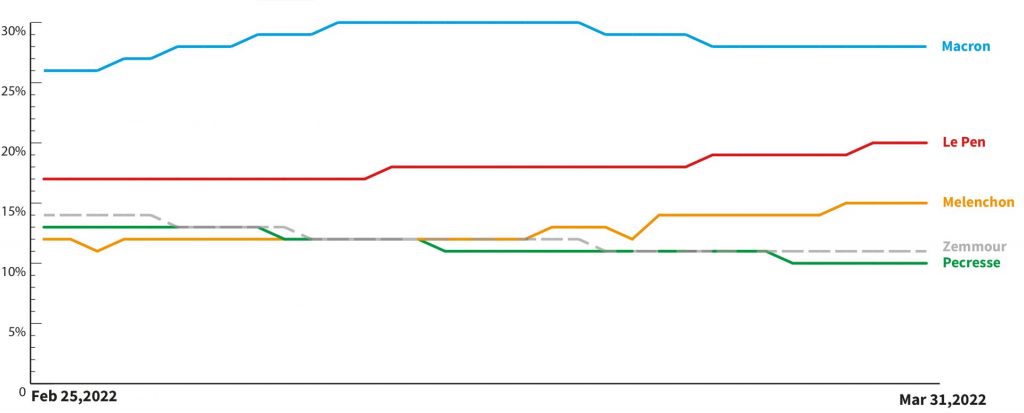

In the first round this Sunday, Le Pen now looks likely to finish second and confront president Emmanuel Macron in the run-off (as she did in 2017). Despite being uncomfortably close to Macron in the average of second-round polling – 45% to his 55% – she will almost certainly lose the second round on 24 April. That will probably be the end of her, although not of her politics.

If you want to be scared (really scared) about the direction of French politics, you must look further ahead.

The most singular fact about this French campaign – until the Ukraine war intervened – was the doublebarrelled offensive of the anti- European, xenophobic extreme right. Zemmour’s attempt to both supplant Le Pen and to colonise part of the centre right was remarkably successful until his antecedents as a Vladimir Putin enthusiast caught up with him. (“I dream of a French Putin,” Zemmour said in 2018).

His support has melted considerably since the war began. Le Pen’s has grown, despite her own considerable pro-Putin baggage. She was lucky enough, or smart enough, to have made the cost of living one of the main planks of her platform from the beginning.

Macron’s initial polling boost from the war has faded as many French people lose interest in the grinding of Ukrainian cities and civilians and grow indignant about the rising price of their own fuel and food. The result, this weekend, and in the second round two weeks later, will be closer than seemed possible two weeks ago. Even so it is difficult to imagine that Macron will lose.

Taking a longer view, what Macron represents – the mainstream French politics of the last half century, pro-European, socially progressive, outward-looking – can no longer be guaranteed. There are seismic shifts in the French electoral landscape, which were already evident in 2017 when Macron triumphed in the centre. The same forces have helped to shape this year’s election. They may decide the outcome in 2027.

To get a sense of the changes under way, look at any of the many (too many) French opinion polls. The two candidates who represent the political families that alternated in power from 1958 to 2017 – the centre right and centre left – now command a combined 13.5% of the first-round vote.

Valérie Pécresse of the centre-right Républicains, heirs of Charles de Gaulle and Jacques Chirac, has 11%. Anne Hidalgo of the Parti Socialiste, created by François Mitterrand in the 1970s, has a miserable 2.5%.

Both of those parties may well disappear in the next year or so. They have been torn apart by their own failures but also because their former political fiefdoms stand astride the new fault lines of French politics.

France once had (in simple terms) two broad ideological bands of centre right and centre left with small extremes on both wings. Like ancient Gaul under Julius Caesar, it is in the process of dividing into three parts (with jagged edges).

In Britain and the United States, similar shifts are happening within the two-party system. In France, the old, ramshackle party structures have all but collapsed. New structures are struggling to emerge.

I shall call the three “new” tribes of modern Gaul the nationalist right, the broad divided left and the consensual centre.

Opinion polls suggest that around 38% of the French electorate are ready to vote this month for an extreme nationalist, anti-migrant and Europhobic or Eurosceptic candidate of the hard or far right.

At present this tribe – the nationalist right – is split into three sub-tribes. There is Le Pen’s Rassemblement National; there is the TV pundit-turned politician Zemmour’s new party Reconquête; and there is the hardline wing of the main centre-right party, Les Républicains. These three sub-tribes have differing degrees of racial intolerance and they have divergent economic policies. Le Pen’s support is more working class and provincial; Zemmour’s more bourgeois and metropolitan.

On some fundamentals, however, they agree. They want to destroy what they see as the failed consensus of the last 50 years – Europeanist, globalist, allegedly weak on crime and soft on migration.

They want to return to an imagined golden age of the 20th century (or in Zemmour’s case the 19th or late 18th). Some in the Zemmour sub-tribe want to reverse social changes such as gay marriage, advances in women’s rights and the abolition of capital punishment.

The second tribe is the broad divided left (including the Greens) covering around 27% of the nationwide vote (on a good day). They have split themselves into impotence for now.

A section of the old pragmatic, centre left – the left of Lionel Jospin or François Hollande – has migrated to the centrist Macron camp. Some are still marooned within the failing Parti Socialiste or the more practical end of the Greens.

Jean-Luc Mélenchon, leader of the hard-left sub-tribe La France Insoumise (France unbowed), hopes to pip Le Pen next week for second place in the second round. He has 15% support in the first-round polls, 5 points behind Le Pen and 12 points behind Macron. He has been rising fast but will probably fall short.

Even if Mélenchon reaches round two, he will be squashed by Macron. The German and British “lefts” have regrouped and revived in recent months. The French left, in government until five years ago, looks as if might be out of power for decades.

Finally, there is the pro-European, socially liberal, progressive but pro-market consensual centre. This tribe has a complex electoral geology covering Macron and his supporters, part of the centre left and a couple of old, small, centrist parties that regard the president as an upstart.

They also include the socially tolerant, economically liberal and pro-European part of the main centreright party, Les Républicains. Some of the latter, including biggish names, are already deserting to a new political movement, “Horizons”, created by Macron’s very popular former prime minister, Édouard Philippe.

Others have defected to Macron during this campaign. They include biggish names like Bertrand Delanoe, the retired former mayor of Paris and Marisol Touraine, health minister under president François Hollande.

This muddled centrist bloc has maybe 35% of the vote. It wants to prepare France for the problems of the mid-21st century. It also wishes to preserve the post-war political settlement – from Europe to the welfare state.

They have differing ideas about how to do both of those things but their worldviews are fundamentally the same.

Thus president Macron, once a self-declared revolutionary, is now a leading figure in a political bloc dedicated to preserving and improving the status quo. So, crucially, is Valérie Pécresse, the floundering candidate of the main centre-right party, Les Républicains (LR).

Pécresse would never admit it but she has far more in common with her electoral enemy, Macron, than with many of her party colleagues. The ideological barbed wire of one of the new political frontiers in France passes through the middle of her ex-Gaullist party, Les Républicains. That has proved electorally fatal for Pécresse.

The man she beat in the Républicains primary in December, Éric Ciotti, MP for Nice, has become de facto leader of the nationalist wing of the LR. He is little distinguishable from Zemmour in his views on migration and Islam. He gives credence to the “great replacement” theory embraced by Zemmour: that there is a deliberate “globalist” policy to replace white people with brown and black people. He wants to build a French Guantánamo and abandon the principle that anyone born in France has a claim to French citizenship.

Since the new year Pécresse has found herself tied to Ciotti as a kind of running mate in a three-legged race. Predictably, they both fell over. Maybe that is what Ciotti wanted all along.

He boasts that he would vote for Zemmour, not Macron, if faced with that choice in a run-off. That question – who would you vote for in round two – has become one of the most explosive issues in a savage campaignwithin- the-campaign on the right.

Zemmour nicknames Pécresse “Madame two minutes past eight”. That is how long it will take her, he says, to endorse Macron if either he or Le Pen reaches the second round when the first-round results are projected this Sunday.

Zemmour is not right about many things but he is probably right about that.

Pécresse will be lucky to come fourth this week – the worst ever position for the French centre-right since the present presidential election system began in 1965.

Consider. The Républicains and their various predecessors – Gaullists, UDF, RPR, UMP – came first or second in eight presidential elections in a row. In 2017 they came a calamitous third. This year they may come fifth. That is a humiliation that the party will not survive in its present form. Neither will Le Pen’s party, Le Rassemblement National, unless she happens to win the election.

For Le Pen to have recovered so strongly from the Zemmour challenge is a remarkable achievement (whatever you may think of her views, admitted and concealed). But her party, inherited from her father, is falling apart.

The RN (ex-FN) finances are in ruins. Several senior figures have defected during the campaign to Zemmour. They include Gilbert Collard, one of her few MPs, and Nicolas Bay, a long-term senior party operative.

But by far the most significant capture by Zemmour was Marine Le Pen’s niece and Jean-Marie Le Pen’s grand-daughter, Marion Maréchal. She was paraded before a Zemmour rally in Toulon in February as if she was a female Lionel Messi or Cristiano Ronaldo, purchased from a rival team.

It may seem that these “transfers” chose to go in the wrong direction – a rare case of rats joining a sinking ship. Zemmour’s campaign, triumphant in November, was already floundering in January and February (even before Vladimir Putin invaded Ukraine).

But that is a short-term perspective. Zemmour’s project – and that of the very rich people around him – is long term. They want to destroy both LePennism (too vulgar) and the old Gaullist movement (too compromised and too compromising). They want to unite the nationalist-xenophobic French right under one banner with at least 38% of the vote – maybe more.

Throughout this campaign, there has been a kind of ideological ethnic cleansing in progress on the French right and centre. Perhaps it would be better to compare it to the “sorting” of apprentice witches and wizards that occurs in the Harry Potter novels.

Right wing politicians who are trapped on the wrong side of the new “ideological frontier” are being “sorted” – or they are sorting themselves – into new “houses”. No prize for guessing which of the houses most resembles “Slytherin”, the Hogwarts School house for the cunning, ambitious and sectarian.

A vice-president of Les Républicains, Guillaume Peltier, was stripped of his title last year for saying that he admired the message of Zemmour – which is anti-Islam, not just anti-Islamist.

Several senior LR figures, such as Christian Estrosi, mayor of Nice, have left the party, complaining that it has betrayed its liberal values and drifted too far to the right. They have joined the so-called “Horizontals”, the new, Macron-supporting centre-right party created by Édouard Philippe, ex-LR mayor of Le Havre and Macron’s prime minister from 2017 to 2020.

Another moderate LR big town mayor, Gaël Perdriau of Saint Etienne, has been demoted within the party for protesting about its rightward drift. He refuses to join Philippe’s new party, Horizons, because he heartily dislikes Macron.

“We are abandoning the heritage of tolerance handed down to us by Jacques Chirac,” Perdriau said. “We should draw a red line between our respect for diversity and the intolerant attitudes of Zemmour and Le Pen.”

Other recent defectors from the centre right to Macron and what I call the consensual centre include Jacques Chirac’s former prime minister, Jean- Pierre Raffarin, and the former Sarkozy-era budget minister, Éric Woerth.

And what of Nicolas Sarkozy himself? The former president (2007- 12) has refused to endorse Valérie Pécresse, the standard-bearer of a party that he created in its present form. There have been persistent rumours that he would instead support Macron. He has not done so – publicly. But the two sometimes lunch together and see eye-to-eye on some things (not all).

There are personal reasons for Sarkozy’s decision to snub Pécresse. She was on another candidate’s side in 2016 when he came an embarrassing third in what he hoped would be a come-back presidential primary.

But senior sources within the LR say Sarkozy believes that the old centre right – his old centre right, the Gaullist centre right – is dead. A part has been irretrievably lost to the kind of nationalist migrant-bashing and Euroscepticism that he himself flirted with as president but never embraced. Sarkozy now believes that the future for the moderate, reforming pro-European right must be to merge with, or absorb, Macronism before the next election (when the president cannot run again).

As the new boundaries in French politics take more solid form, the 2022 French election has been seen by many players as a prelude to the 2027 election. Vladimir Putin has invaded those calculations.

Zemmour is damaged goods for now. The resurgence of Le Pen makes the defectors from her party look foolish. But the pre-2027 manoeuvring will soon resume, starting with the parliamentary elections in June. The new tripartite shape of French politics may become clearer by this summer.

If Macron is re-elected, as expected, efforts will continue to cement, or steal, his legacy by building a more coherent new movement of the pro-European centre. Zemmour and the people around him will try to build a new nationalist force from their own party and the ruins of Les Républicains. They will hope to lasso parts of Le Pen’s movement.

The next five years may be brutal economically and politically – and not just in France. Popular anger and frustration may enlarge the combined hard and far-right vote beyond its current 38%.

Who would lead such an expanded movement? It is unlikely to be Zemmour. A likely contender is Marine Le Pen’s niece, Marion Maréchal, even though she has plenty of pro-Putin baggage of her own.

Zemmour believes women are unsuited to high political office. Maréchal does not.

France’s “Trump moment” – or its “Brexit moment” – may not be so imminent as The Spectator or the Daily Telegraph would like. But they may be happier in five years’ time.

John Lichfield is a former Foreign Reporter of the Year who has covered French-UK relations from Paris since 1997.