While everyone is losing theirs, Keir Starmer is keeping a cool head. The message from Downing Street, ever since Donald Trump was inaugurated and America’s descent into chaos began, is that the prime minister will keep calm and carry on.

British leaders tend towards the rhetoric of leadership. Thatcher was “no, no, no” against a pernicious Europe. Tony Blair was modernising while bombing in a good cause. David Cameron was there “because I’m good at it”.

Starmer is one of a troika, with John Major and Gordon Brown, who feel threatened by charisma. Now in this time of poly-crisis, he is making a virtue of necessity – the man who says little, while other leaders head to social media to make florid denunciations of the man in the White House.

Yet in staying demure, Starmer stands accused of being weak, worse of appeasing fascism. He reinforces the suspicion that, like his predecessors, he is psychologically unable to wean the UK away from its yearning to be teacher’s pet.

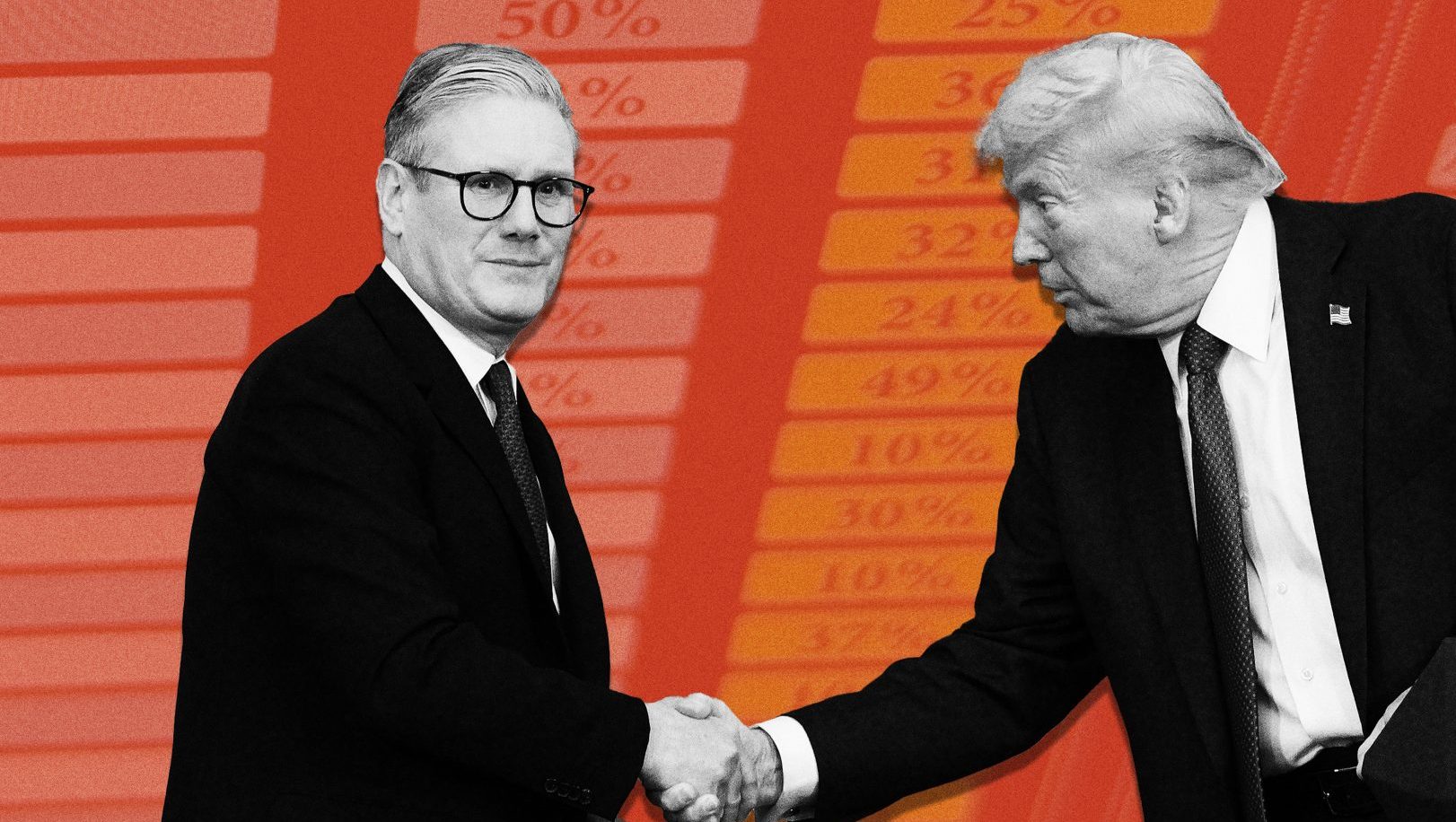

That first meeting in the Oval Office, all smiles as he unctuously unveiled an invitation from the King for another Trumpian state visit, is not the kind of thing confident countries do. Yet is it any different from others? President Macron, three days earlier, had tried the same charm offensive: that hand on the knee will linger in the memory.

Ultimately, it is about hard results. What works best: humiliation or revenge? Trump must have enjoyed declaring that Starmer was “very happy” that Washington has planned to slap “only” the baseline 10% levy on British exports. Starmer will not have been so delighted. He did not take the bait but instructed a spokesman to reiterate London’s “disappointment” over the move: “We accept that the tariffs imposed on the UK put us in a relatively more favourable position than other countries, but of course, the impact on the UK will be real”.

The eagerness always to be at America’s right hand is deeply embedded in British political psychology. It was that way before the UK joined the EU, even while it was a member, and since Brexit is even more so. It is based in a small amount of hubris and a large lack of confidence.

The New York Times was disdainful of the Starmer approach. “After all that – the chummy Oval Office meeting, the extraordinary royal invitation, the paeans to the “special relationship” – Britain and its solicitous prime minister, Keir Starmer, still got swept into President Trump’s tariffs.”

Just over a week before Trump’s fanfare announcement, even as Rachel Reeves was delivering her spring statement, ministers were clinging to the notion that niceness wins reprieves. One official was quoted as saying they were “hoping and working towards a resolution before April 2 and not after.”

As “Liberation Day” beckoned, optimism diminished. Starmer rushed to the phone, suggesting to the Americans a visit as early as June to sign a trade deal. That too didn’t work. Trump announced a universal 25% tariff on cars and car parts coming into the US, a move that would hit countries like Germany particularly hard. But Britain too would feel the pain, with Jaguar, Bentley, Rolls-Royce and Aston Martin particularly exposed and thousands of jobs at risk.

Most upsetting to the Brits is that they had no inkling of his plans. It is an article of faith that in this so-called “special relationship” – conferred by the powerful to the meek with a pat on the head – the Americans will at least tip off their favourite underlings before doing something dramatic.

The first wake-up call on the front came in January 2002 when President George W made his “axis of evil” speech to Congress, presaging war with Iraq. Tony Blair made it clear to his embassy in Washington and his aides in London that never again would he find out about something from the TV.

Fourteen years on, and for Downing Street it was back to late-night viewing of Trump and his whiteboard of errant trading nations to learn the country’s fate – a “mere” 10% on the UK compared to the 20% for the EU.

Cue the crowing from a certain set that, whether it was his intention or not (and they see him as one of their own), Trump is “making Brexit work”. Britain can finally become Singapore-on-Thames, the low-tax, low-regulation, low-tariff irritant of the European continent.

Some in Brussels harbour a similar thought, framed in a different way, that Trump is bringing a hard Brexit to its logical conclusions. The final act of the decoupling of the UK from Europe might now begin, as Britain uses the tariff differential to strike out on its own.

Many in the Commission and among member states have feared that Trump would always exploit the UK’s position outside the bloc to drive a further wedge. It is a byproduct of the wider aim, shared by Trump and his close ally, Vladimir Putin, of undermining the EU from inside and out.

Starmer insists it’s not about which side to come down on, pointing to the much warmer relations in security of recent months. Macron and Germany’s incoming chancellor, Friedrich Merz, are keen to bring the UK in from the cold in a new “coalition of the willing” on defence.

Defence cooperation must hold, but it is a more open question whether the recent camaraderie extends to economic cooperation – or perhaps a better term now, mutual assistance – given the parlous state of Britain’s public finances. How far will Starmer go to mitigate the effects of Trump’s madness, to give Rachel Reeves more wiggle room for what is already set to be a difficult budget in the autumn?

While claiming he is keeping his options open, the prime minister has shown little sign of planning reciprocal tariffs. The government is going through the motions, preparing a 417-page document detailing potential products that could be taxed. The list covers only 27% of imports from the US – from purebred horses and children’s clothes to crude oil, firearms and bourbon whiskey – chosen because they would have a “more limited impact” on the UK economy. It is unlikely to be instilling fear in Washington.

The hard reality – one of the many tragedies of Brexit – is that the UK is too small to win a fight on its own.

Instead, Starmer is holding out for Whitehall’s fabled economic deal with the US. But haven’t we been there before? Didn’t the much-missed Liz Truss, when trade secretary, proclaim that a new dawn would emerge with a trade agreement with Washington? It didn’t happen. In fact, the very few deals that the UK has struck, such as with Australia, have been highly damaging to British farmers.

In looking for enticements, Starmer’s negotiators appear to be ready to reduce the headline rate of the Digital Services Tax on US tech firms while applying the levy to companies from other countries. The tax, introduced as a stop-gap measure in 2020 pending an international agreement that never materialised, sought to make tech giants not headquartered in the UK pay a tax on the revenues they made from their UK users.

Even though it is modest – a mere 2% on the revenues of search engines, social media services and online marketplaces – it raises £800m a year. All income is good income in times like this.

Its symbolic value is greater. For Trump and his Silicon Valley backers, it is an insult. By removing it, Starmer will curry favour with them. He will also be seen by many at home as kowtowing. If he reduces the tax rather than cancels it, he may satisfy neither constituency.

He would also put further distance between the island nation and Europe. The EU has been at the forefront of regulating big tech, including via its AI Act, introducing similar digital tax regimes alongside GDPR data privacy laws.

The hard reality – one of the many tragedies of Brexit – is that the UK is too small to win a fight on its own. Perhaps only the EU and China have such clout. Hence, apart from goodwill, letters from the king and golfing days out in Scotland – Britain has no levers.

Starmer is the unflashy pragmatist. Waiting and seeing is not a bad tactic for now in these extraordinarily dangerous and febrile times. But it is not a strategy, and relatively soon he is going to have to decide which way to turn. It is not a binary choice, but it is a clear statement of long-term commitment.

He is not alone. All other leaders face similar dilemmas. Who in the end will have mitigated Trump’s worst instincts? Who will have come out of the mayhem in the least-worst situation?

The answer is: nobody knows. Nobody will know for a long time, indeed if they ever know. For as Trump is around, he will luxuriate in riling his counterparts. The man whose every utterance is hung on. The man who moves markets. And all made for TV.

John Kampfner is an award-winning author, columnist and foreign affairs specialist