It is “code red for humanity”, declared UN secretary-general Antonio Guterres. The world, he exclaimed, is running out of time. The language on climate change is becoming ever more dramatic as successive reports set out the consequences if emissions are not cut significantly – and urgently.

According to the latest expert forecasts, the current crop of national commitments is leading the world to heat up by close to three degrees. Temperatures such as those would trigger what scientists call a “cascade” in which one disaster provokes another with ever wider economic, social, and geopolitical consequences.

That is the future. The present and past are already alarming enough.

The World Meteorological Organisation says the number of disasters such as floods and heatwaves driven by climate change has increased five-fold in the past 50 years. This is the context as world leaders and experts head to Glasgow for COP26.

Just before that, the G20 meets in Rome. The summits are taking place at the worst possible time, with countries struggling to see off the pandemic and restart their economies. They are promising to ‘build back better’ but early evidence shows they are building back as fast as possible – which means doing whatever it takes to kick-start growth, including high-emitting infrastructure projects.

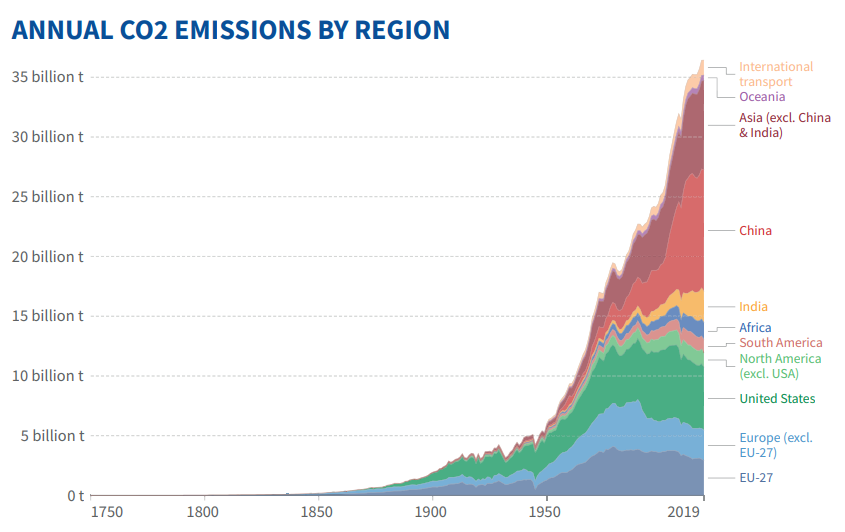

After an enforced hiatus in 2020, emissions figures for 2021 are extremely worrying with little sign of improvement – the projected global increase of 1.5 billion tonnes, if correct, would be the second-largest increase in history.

All of this is coming when the most dangerous big-power rivalry since the Cold War is escalating. The US regularly chastises China over its treatment of Uighurs in Xinjiang and its clampdown in Hong Kong, alongside threats to Taiwan, tensions in the South China Sea, and cyberattacks. The announcement of AUKUS – a joint US, Australia, UK project to build nuclear-powered submarines for Australia to deploy in the Indo-Pacific – has further exacerbated tensions.

Climate is the ultimate test of whether it is possible to simultaneously compete for dominance of the world and collaborate to save that world. If the US and China cannot work together on this, if they cannot bring other countries along with them, then where else can they?

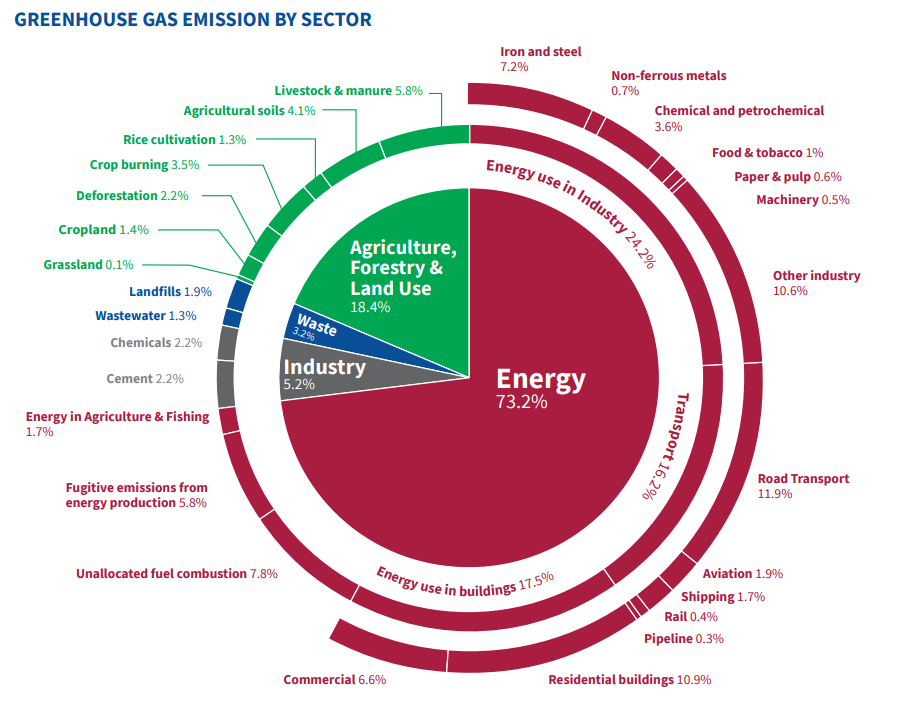

The US and China are jointly responsible for 40% of greenhouse gases. Logic dictates that without them coming together, no meaningful progress will be made, multilaterally or bilaterally. To put it another way, we are all doomed.

The evidence so far suggests that conventional diplomacy – a combination of carrot and stick, of the handshake and the megaphone – is not working. Yet all sides know they must act rapidly in order to prevent catastrophe, not least for their own populations.

The most likely triggers for radical change lie elsewhere and are based on national self-interest. Which big power, which political system, will seize the mantle of the green global citizen and drive action by other governments around the world? Which will seize the huge economic benefits arising from green technologies?

These two challenges stem from rivalry and competition but a third one is self-preservation. At what point will populations begin to appreciate that inaction on climate is imperilling them? How bad will it have to get before they demand radical change, even in authoritarian states?

The major powers are still trying old-fashioned diplomacy. In the first 100 days of the Biden presidency, the US held a series of talks with China. At the first meeting, in Alaska in March, China’s senior foreign affairs official, Yang Jiechi, launched a tirade against Antony Blinken after the US secretary of state attacked China’s human rights record.

In April, president Biden’s climate envoy, John Kerry, became the first senior official of the new administration to visit China, for talks with his counterpart Xie Zhenhua. President Xi Jinping then attended an online leaders’ climate summit convened by Biden. Kerry and Xie have talked, online and face-to-face more than a dozen times.

It remains unclear what these various meetings have achieved.

Their most recent, in Tianjin at the start of September, was described as “constructive and detailed” – about as good as it gets in the circumstances. So, what are the prospects of one side coaxing the other to improve its climate performance?

First the positives. COP26 is taking place a year late due to the pandemic, and the time-lag has provided some distance from the Donald Trump era. Within days of taking office, Biden signed a series of executive orders on the environment, directing the government to make climate change a central issue of his.

Among its measures were orders to freeze new oil and gas leases on public lands and double offshore wind-produced energy by 2030, alongside fulfilment of a campaign pledge to re-join the Paris accords.

In Kerry, the US has a negotiator of considerable stature internationally and he has certainly been energetic, shuttling around the world in his attempts to cajole states to sharpen their commitments.

But there are three fundamental weaknesses in the American – and, by extension, its allies’ – negotiating strategy. Firstly, the international community is factoring in the strong possibility of a return of Trump – or at least ‘Trumpism’ – to power.

Given the extent to which climate is a deeply polarising issue in the US, some of the most radical climate action by Biden will have to be signed by executive order which can be swiftly reversed.

Secondly, the Biden administration insists climate talks must be separated from other issues. Kerry has sought to kill from the outset the notion that China could buy US silence on human rights and other issues as the price of cooperation on climate. This tough line appears to be working as most Republicans and Democrats are holding to it, but civil society groups are challenging it. In July, 40 progressive groups argued that “nothing less than the future of our planet depends on ending the new Cold War between the US and China”. China hawks were furious with the intervention.

China also made clear on the eve of Kerry’s Tianjin talks that any thought of splitting climate from other policy issues is a non-starter. Its foreign minister Wang Yi described joint efforts against global warming as an “oasis” but added the oasis “could be turned into a desert very soon”. In case the Americans hadn’t got the message, he summarised that China-US climate cooperation “cannot be separated from the wider environment of China-US relations”.

The third weakness is the most intractable. Even before the Afghanistan debacle, American power – hard and soft – is not what it was. Exhortations to China or to other countries do not have the effect they once did. Even US allies are doing their own thing.

The EU Green Deal is one of the most radical on offer while, by contrast, Australia – whose strategic importance in countering China in the Indo-Pacific is growing – is one of the world’s most defiant climate laggards.

The US failure so far to keep to its side of the economic bargain on climate has fuelled further misgivings. Biden has struggled to persuade wealthy countries to meet their long-standing commitment to stump up $100 billion in climate finance per year to help poorer states deal with the effects of climate change.

They have been warned adaptation costs, currently estimated at $70 billion per year, could soar to $300 billion per year by 2030. Developing countries stress this funding is key to their ability and willingness to commit to ambitious climate targets, and therefore to broader ambitions of global net-zero. In his speech to the UN General Assembly, Biden vowed to double the US contribution to the target and to bring allies along with him. The rhetoric was compelling, but it is questionable how substantial his claims will turn out to be, whether he gets the extra money through Congress, or if others will come on board to hit the $100 billion. Even if money is found at the 11th hour this year, there is no guarantee it will be met in subsequent years.

The United Nations was the venue for a dramatic intervention in 2020 by China when Xi told the General Assembly his country aimed to have carbon emissions peak before 2030 and to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060, calling on all countries to “pursue innovative, coordinated, green, and open development for all”.

Although China had given the first date before, it had not committed to a date for net zero – and it did so ahead of the US. This was a remarkable announcement which blindsided Chinese and international officials and experts.

China’s climate announcements since Xi’s speech have been less impressive.

The Communist Party’s 14th five-year-plan, covering the period to 2025 and published in March 2021, mentions carbon neutrality only once in a 75,000-word text. And Xi’s recent UN speech broke new ground in only one specific area, when he pledged China would build no more coal-fired power projects abroad.

Beijing has been under pressure to end coal financing overseas following similar announcements by South Korea and Japan. These three countries are responsible for more than 95% of all foreign financing for coal-fired power plants. But this concession is relatively low-hanging fruit as recipient countries were becoming increasingly wary of such projects.

Choreography matters in moments such as these. Not wanting to be blamed is a big part of the Chinese mentality. Beijing was castigated as the villain at the Copenhagen talks in 2009. Last-minute talks with the Obama administration ensured last-minute success in Paris in 2015.

China is keen to show its announcements are not because of pressure but are entirely on its own terms.

“The Chinese won’t be pushed around,” says Mikko Huotari, executive director of the Mercator Institute for China Studies in Berlin, “nor will other countries. This is a game of waiting – and hoping for the signals.”

China has come a long way, cleaning up air pollution and investing heavily in renewable energy. Its fixation with GDP growth is not what it was, and the term Gross Ecosystem Product (GEP) has come into official fashion.

Back in 2005, as a regional party chief, Xi cited an old Chinese proverb ‘clear waters and lush hills are worth a mountain of gold and a mountain of silver’. Known as the ‘two mountains theory’, this has become a mantra for regional governments to build a more ‘ecological civilisation’.

Alongside this are economic opportunities. China has seized on the potential benefits in new greener technologies for domestic and export markets and Xi is keen to harness the dynamic in this ‘race to the top’ – both in terms of growth and international reputation.

Soft power competition also sits alongside economic competition. Which country, which system, can transition into a more competitive 21 st century clean-energy, zero-carbon economy is the long-term goal, but that remains a long way off.

Five of the top ten global wind turbine manufacturers are Chinese – such is the scale of China’s economy it produces more renewable infrastructure than the rest of the world combined, bringing down the cost of solar, wind, and other resources.

Even in a country as tightly controlled as Xi’s China, domestic pressures are considerable. For all the flowery talk of GEP, coal remains mission-critical for growth, comprising two-thirds of total energy consumption. China now generates 53% of the entire world’s coal-fired power and is increasing capacity all the time.

Experts say it must shut down more than 500 coal-fired plants within ten years to have any chance of reaching its climate targets and, for the moment, that is not happening.

China is in the throes of a post-pandemic ‘smokestack recovery’. Emissions have grown at their fastest pace in more than a decade, increasing 15% year on year in the first quarter of 2021.

Huotari argues the reliance on coal is based on wider considerations. “Resilience and energy security are paramount in Chinese policymaking. Coal has always been central to that,” he says. “It is very hard to give up that mentality.”

Recently, 10 provinces were forced to ration energy because of a slump in production, triggering alarm and pleas for more, not less, coal.

Isabel Hilton, founder and senior adviser at China Dialogue, summarises the dilemma: “China is acutely aware of the opportunity side of climate change and has positioned itself for more than a decade to be the world’s dominant supplier of low carbon goods and services,” she notes.

“But domestically, despite a rapid deployment of renewables, the complicated economics of the transition in a country still heavily dependent on coal, and concerns about energy security in an increasingly tense world, appear to be slowing the pace of China’s effort alarmingly.”

As in the US, climate justice is gaining prominence in China, with a suspicion that jobs related to renewable energy and environmental transformation are less well-paid and have less social value than traditional industries. This reflects culture clashes playing out across the world between younger, greener, city dwellers and older, more traditional, citizens in ‘rust belt’ towns.

In the case of China that is predominantly, but not exclusively, in the north-east of the country, where an increasing nationalism is taking hold in which climate change is denounced as ‘Western pseudo-science’ and a conspiracy to stem China’s growth.

Set against that are the shocks experienced in recent years – in 2021 alone, wildfires raged in Canada and the US Pacific Northwest as temperatures topped 50 degrees, New York’s subway was engulfed by water, floods tore through German, Belgian, and Dutch towns and villages.

Importantly, this was in China too. On July 17, terrified subway passengers in Zhengzhou stood in chest-high water as almost one year’s rain fell in just three days and more than 300 people were killed across Henan province.

As a major transport hub, Zhengzhou’s lines were built only five years ago and were supposed to be able to withstand climate emergencies. Local authorities were subjected to unprecedented criticism on social media, with fury over infrastructural shortcomings and failures in weather forecasting.

Xi hesitated to go there, foreign journalists were harassed when seeking to interview affected residents, and state media dwelt instead on the ‘heroic’ efforts of the People’s Liberation Army and the gratitude of those rescued.

Climate is producing a series of potential vulnerabilities for China, a potential cascade.

The East coast, where the wealth is concentrated, is particularly susceptible to rising sea levels, and power supply shortages have occurred in several cities.

Like Biden, Xi has declared the climate crisis to be a strategic priority and an issue of national security. He has good reasons to act.

Food security and water resources would be imperilled by runaway

climate change.

The party worries particularly about protests among the rural population, which could happen with another big weather catastrophe resulting from climate change, or because of further measures to diversify away from traditional energy leading to power cuts and job losses. The government has to look in both directions at the same time.

With a nod to its domestic audience, as well as to developing nations and the international community, China’s leadership demands others cut it some slack. It reularly falls back on the argument that it is merely catching up and should not be subjected to the same strictures as the US and Europe, which have been emitting far more for far longer.

The US is historically the largest emitter, accounting for 29%. The EU – including the UK in the past – is at 22% and China at 13%.

But China is catching up steadily and some estimates suggest if it continues at its current pace, by 2035 it will have overtaken all others – an ignominious milestone and devastating for the world.

The bidding war for green credentials will intensify in the coming days as COP26 approaches, with virtue signalling and admonishments aplenty.

The real challenge takes place after the summit when climate issues may no longer dominate the media and it will become about more humdrum questions of complying with targets.

This is a proxy battle taking place within a wider Cold War as the competitive instincts of the US and China propel both to try to outshine each other in new technologies and surprise announcements.

Ultimately though, more would be achieved if suspicion reduced and collaboration increased. As Leslie Vinjamuri, director of the US and Americas Programme at Chatham House, points out, the world struggles to make meaningful climate progress in a vacuum.

“You can pretend you are moving the silos forward but there comes a point at which you have to make trade-offs.”

This report was originally published by Chatham House.