“Hot prawns in olive oil and great wine and the soft sweet smell of Greek pine leaves. I shall never come home. How can I?” Everyone has felt that holiday longing at some time, but for the artist John Craxton settling abroad from his native Britain was not so much a pipe dream, more a vocation.

He was writing in 1946 to fellow artist EQ Nicholson, sister-in-law of the St Ives artist Ben Nicholson and one of his huge coterie of well-connected and artistically minded friends, having finally landed in Athens after many years working his way towards the country that he sensed would be his spiritual home. He landed there by dint of being given a lift in a bomber, briefly requisitioned by the wife of the British ambassador to Greece, Lady Norton. She needed to airlift from Milan vital Italian curtains sourced for the embassy, and had offered the likeable young man a ride.

Such luck seasoned with glamour would follow Craxton throughout his long life, and when necessary, he would engineer it. Five years after that flight to paradise, he persuaded wealthy US patrons to fund a cruise around the Greek islands for himself, ballerina Margot Fonteyn and choreographer Frederick Ashton. The three had just worked together on a dance version of Ravel’s Daphnis and Chloe. In for a penny in for a pound, he instructed the writer Patrick Leigh Fermor and his future wife Joan Rayner to stand by on the quayside before embarkation, as if by chance, and wangled their passage as well.

This talent for living stemmed from birth. John Craxton was the fourth of the six children of Harold Craxton, Royal Academy of Music professor, pianist and composer, and his violinist wife Essie Faulkner. It was a happy, chaotic and unconventional childhood, as described colourfully by Craxton’s biographer, Ian Collins, and all his siblings became prominent successes in their own fields, notably sister Janet, the renowned oboist. Harold Craxton wasn’t above penning light music, and sales of sheet music of his song Mavis were enough to pay for a shack near the beach at Selsey and thereby for many years of affordable family holidays in Sussex. The family of eight were driven by Essie in a titchy Austin 12, the three older boys hanging off the back as the car did a lap of honour around the market cross in Chichester.

Even in this talented family, probably no one could have foreseen that little John’s artwork would one day take pride of place at what is now Pallant House Gallery, a few hundred metres away. It is in the exhibition John Craxton: A Modern Odyssey, curated by Collins, that the life and art of this idiosyncratic Grecophile is told in more than 100 works – primarily paintings, but also set designs, drawings, letters and book jackets.

Frequently joining the throng in the family home in St John’s Wood, north London, were music students who came to eat and pretty much never left, a practice which may have influenced his own modus vivendi. Music was the warp and weft of the young John’s life, at home and at the Prebendal School in Chichester, where longueurs for a chorister in the choir stalls were enlivened by study of the cathedral’s architecture and, imprinted on his memory, two Romanesque bas-reliefs. Otherwise his education was patchy and eclectic, and he passed not one test, but for that which allowed him to take to the road on a motorbike.

He was probably at his happiest going to live with an aunt and uncle who were painters, shortly after making an impression at the age of 13 in a display of school work at the Bloomsbury Gallery. Living with or off others became his stock in trade, considerable personal charm proving to be an extremely bankable currency. He adored cats, and appears to have modelled his lifestyle on theirs.

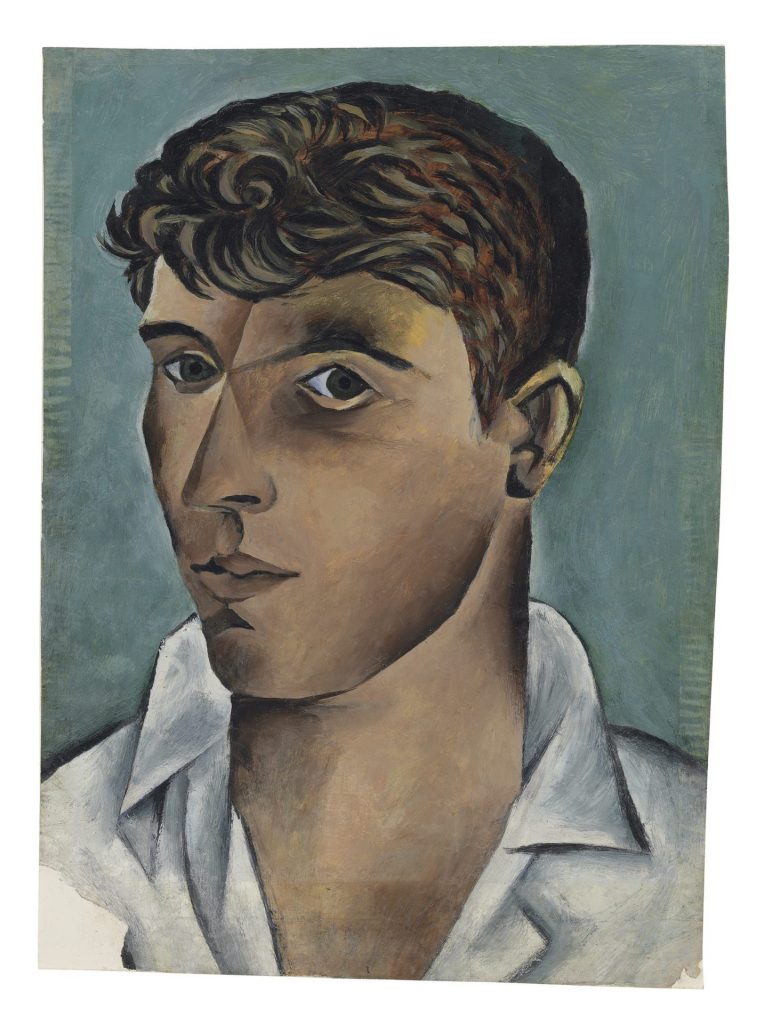

Study of Hellenistic art at the old Pitt-Rivers museum in the village of Farnham in Dorset, near his adopted home, helped nurture a love of ancient Greek figures and portraits that would underpin his affection for modern Greece, and its irresistible attraction for him. Alongside the Nicholsons, he also got to know British surrealist Roland Penrose and photographer Lee Miller, and through a magazine publisher friend met Paul Nash, John Piper, Graham Sutherland and his exact contemporary Lucian Freud, with whom he set out on literal and artistic adventures.

The influence of early-years exposure to art and artists echoes through Craxton’s early work. In Rotted Hen (1943) is Sutherland’s spikey and visceral vision of the natural world. Poet in Landscape (1941) recalls Samuel Palmer’s rural idyll, its figure tightly knotted into the flora. An instinct for travel – he was already drawing in Paris by the age of 17 – was curtailed by the second world war. Visiting Sutherland in Pembrokeshire, he learnt from the older artist how to look at landscape, but Wales’s rugged south-west coastline was no substitute for the Aegean vistas he yearned for.

With travel limited even after wartime, at the suggestion of artist Julian Trevelyan, he made do with the Isles of Scilly, setting out with Freud, the pair a couple of likely lads. Greek Fisherman (1946), the first picture on this theme, was a fantasy – it was painted in Tresco. But at last, with the encouragement of Greek artist Nikos Ghika, he had Greece in his sights. With tours of the Dodecanese and the Cyclades and the first of what would become annual visits to Crete, he was in his spiritual home.

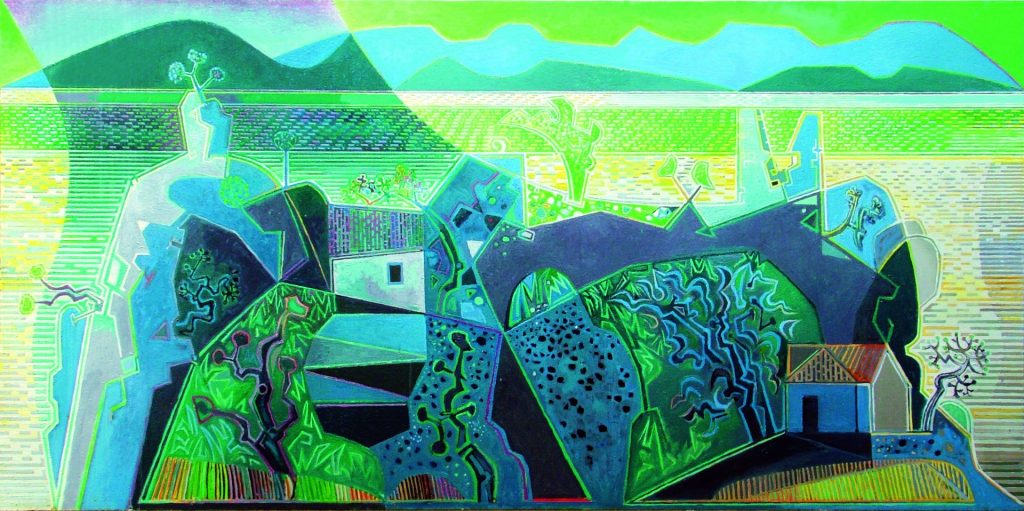

Here he found the elements that would recur for decades, albeit through a succession of styles. Men who made their living from nature – nonchalant fishermen, sure-footed farmers – work and relax amid goaty trees and tree-like goats, good, sun-ripened produce, under azure skies and released from azure seas. With rationing still in place in Britain, this land of plenty has a dreamlike quality. The taverna table is richly spread, the fish stall in Poros is tipped towards the viewer with its offer of flatfish large and small and all manner of tentacles.

With his musical background and artist’s eye, he was drawn to dance, capturing the distinctive side-steps of the solitary Greek man responding to traditional instrumentals. The wrists, arms and shoulders of Man Dancing in a Taverna are formed of a single curve. So too the backs of a pair of cats playing on a chair, two hemispheres teased into a circle. An early fascination with Picasso and Cubism underpinned a geometric approach to much of Craxton’s work, but no artist is immune to the seductive sweep of a sinuous arc.

This passion for dance – and briefly for Fonteyn – paved the way to his landmark 1951 design for Daphnis and Chloe, choreographed by Ashton. He returned to Covent Garden in 1966, designing the UK premiere, almost 40 years after its premiere in Washington DC, of Apollo, with music by Igor Stravinsky and choreography by George Balanchine. The following year, the Whitechapel Gallery in London staged a Craxton retrospective, with more than 150 works.

By now, he had found his forever house, in Chania, Crete, the restoration of which would be his life’s work, albeit incomplete. But his art was not lost to this vast undertaking, and he continued to design striking book jackets for the travel writings of Leigh Fermor, eye-catching covers that are now collector’s items, and he had an eye for ceramics design, producing in the 1970s with potter Ann Stokes pieces with pleasing repeats in traditional blues and whites.

That association began after his expulsion from Greece under the military regime, in 1967. He travelled widely and spent two years in Edinburgh, designing for the University of Stirling a large, Aegean-inspired tapestry, filled with light and colour, that was produced at Dovecot Weavers in the city. He had already experimented with textural or mosaic-like application of colour in works such as Two Figures and Setting Sun (1952-67), in which the normally azure sea glimmers pink, green and yellow, and the low sun hits the reclining man like a spotlight.

Finally returned to Crete in 1976, Craxton helped with the transfer to the Benaki Museum of Nikos Ghika’s house and studio. A second historic house purchased on Crete by Craxton would in its turn be declared a Greek National Monument, after his death in 2009 at the age of 87.

But for all his long life and varied work, perhaps the carefree piper in Pastoral for PW (1948) best encapsulates Craxton’s joyful Grecian life. Painted within two years of his arrival in Crete, the whimsical goats have a whiff of the portraiture of friends (including his patron and friend Peter Watson, the PW of the title), the figure is largely autobiographical, and the landscape is exuberant and fantastical.

That same year he wrote to EQ Nicholson again, abandoning punctuation in favour of local colour: “I am off again in a day to an island where lemons grow & oranges melt in the mouth & goats snatch the last fig leaves off small trees the corn is yellow and russles [sic] & the sea is harplike on volcanic shores saw the marx brothers in an open air cinema & the walls were made of honeysuckle.” Who could ask for anything more?

John Craxton: A Modern Odyssey is at Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, until April 21, 2024. A book of the same name, edited by Simon Martin, with contributions from authors including Ian Collins, David Attenborough, Tacita Dean and Hilary Spurling, is published by the gallery (£30)