If you evaluated American taste only via the people we’ve acceded power and influence to over the last decade, you might conclude that Americans have a particular fetish for elevating reality TV stars. We elected a president, Donald Trump, who has never been a good businessman, but played one on television, where he pretended to fire people who were not his employees. Each Kardashian sister has her own successful commercial enterprise with assorted brand extensions – cosmetics, perfumes, shapewear, various ex-boyfriends.

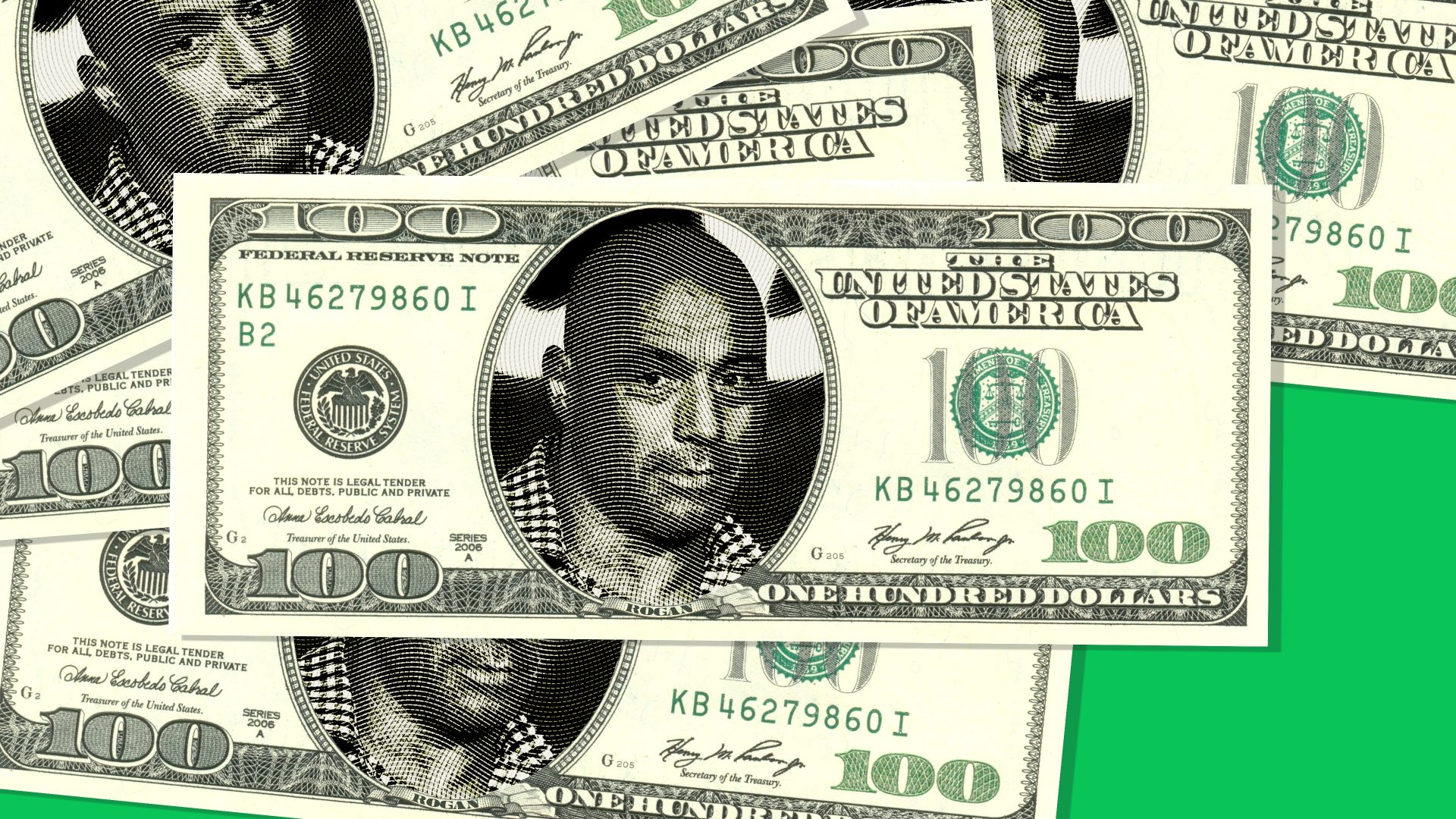

Most recently, Spotify gave 54-year-old former UFC commentator and comedian Joe Rogan $200m for exclusive rights to his podcast, which has 11 million listeners per episode. Rogan was previously the host of Fear Factor, a show where he directed contestants to attempt dangerous challenges and eat disgusting things, sometimes while covered in spiders. Remarkably, this made Rogan seem relatable to a non-trivial part of the American viewing audience.

He is a controversialist who recently explained the Ukraine conflict thus: “Nato is invading, is encroaching on Russian space. They’re… making these countries join, or having them join and then they would park weapons next to Russia.”

Rogan has gone on to claim that people “on both sides” have discussed how Ukraine has “A Nazi problem” and alleged that before the war, leftists viewed Volodymr Zelensky and his government with deep suspicion.

“This is one of the things that’s so weird is that they were very disparaging of Ukraine, and they were talking about the massive corruption of Ukraine, and how horrible it was over there,” he said. “And now, all of a sudden, they’re looking at it like they’re heroes. The same exact people. This is what’s confusing.”

For evidence, he offered “this screenshot that someone sent me”. This may be part of the problem with Joe Rogan.

His views on Ukraine are part of the ongoing controversy that defines Rogan; that is, what can and cannot be said on, say, a podcast with 11 million listeners. One line of criticism is that Rogan has actively spread Covid-19 vaccine disinformation, by hosting notorious vaccine sceptics like Dr Robert Malone, who among other things, compared vaccines to Nazi medical experiments, and seemingly agreeing with some of Malone’s assertions. When Malone suggested, with no evidence, that President Joe Biden did not actually receive the Covid vaccine when America watched him do it, on television, Rogan did not push back, but implied that it was plausible.

Unsurprisingly, this sort of thing makes Rogan a magnet for the tin foil haberdashery set, and he has done little to discourage the conspiracy-mongering that has led an unfortunate number of Americans to trust YouTube videos claiming that the best cure for Covid is a horse dewormer more than they trust the Center for Disease Control, or even their own personal physicians. Rogan does this in the same way that intentional propagandists do, by amplifying the conspiracy and claiming that he’s “just asking questions” and telling people to “do their own research”. Since the average Rogan listener is incapable of conducting a double-blind clinical trial, research generally amounts to more YouTube videos.

Spotify has decided that spreading vaccine disinformation is mostly fine, because it does not want to be in the business of what it calls “censorship” but is known as “editing” when other publishers of content do it. But not everyone on Spotify’s platform feels the same way. Musicians Neil Young, India Arie and Joni Mitchell, among others, pulled their music from the platform in protest.

In January, 270 scientists and healthcare officials also sent an open letter to Spotify to protest against the “false and societally harmful assertions” that Rogan and his guests had made, and that had the effect of making Spotify double down on doing absolutely nothing.

Covid disinformation is only part of Spotify’s Rogan problem, though. Its other problems stem from other things Rogan has said on his podcast – namely the n-word, 24 times, which came to light when musician India Arie posted a video compilation of him saying it repeatedly. He has also hosted alt-right figures like Proud Boys founder Gavin McInnes, Milo Yannopoulis, and InfoWars’ Alex Jones, and this has attracted people who prefer white pointy hats more than the tin foil variety.

Rogan’s defenders insist he is not actually racist, and that when he said the worst racial slur in the English language, 24 times, it was taken out of context. But it’s hard to imagine what sort of context could possibly be missing when he also notoriously told a bi-racial guest that he had a “powerful combination” of “the body of the Black man and … the mind of the white man”.

This is somewhat complicated by the fact that Rogan is difficult to pin down politically – he claimed to be a fan of Bernie Sanders, but voted for libertarian long shot Jo Jorgenson in the 2020 presidential election. He has called Barack Obama “the best president that we have had in our lifetime” (which Rogan defenders also like to bring up as evidence that he’s not racist), but his audience skews white, straight, male and middle-aged – for a reason. He also has a history of making misogynistic, homophobic and transphobic comments. So it’s reasonable to infer that the audience most likely to tolerate those things skews conservative, regardless of what box Rogan checks on his ballot.

You can see a glimpse of this on Rogan’s Instagram account, where he eventually apologised for saying the n-word. Rogan supporters were very willing to forgive him, but more to the point, many of them were openly annoyed at the apology. “Why do black people used [sic] those words among themselves, that us as white people get terrible backlash for? Makes no sense,” wrote one commenter. “You caved to cancel culture,” wrote another one. “I thought you were the tough guy?”

Which brings us back to a big part of the reason Rogan has such a large audience: he attracts a type of listener who believes that there should be no limits on speech, even if it’s harmful to others. That listener also tends to conflate free speech principles with a licence to say anything, anywhere, and if Rogan is any indication, to be handsomely compensated for it.

But that is a failure of American civic education, which in theory teaches schoolchildren by the time that they’re 12 or so that the First Amendment protects speech from government intervention. It does not protect people like Joe Rogan from having to meet the standards of the private company that’s paying him, or from public accountability, and it does not protect his ability to make a living from whatever he wants to say.

In this sense, the Rogan superfans also conflate accountability with censorship, because censorship gives them a bit of moral high ground. Rogan has not experienced actual censorship, or even the standard process of editing that professionalised podcasts are typically subjected to.

Since Spotify is paying for exclusive access to Rogan’s show, it is effectively acting as a publisher, and is responsible for what he produces. It would not be unreasonable for it to impose constraints on what Rogan actually puts out. Speech is constrained on private platforms all the time, including on Spotify, which won’t host, for example, a podcast for neo-Nazis.

The commenters on Rogan’s Instagram agree to speech constraints when they sign up and agree to terms of service – they cannot threaten or harass other users on the platform, or use hate speech. This is self-evidently not censorship, but Rogan’s defenders insist that freedom of speech means infinite licence. They want Rogan to be able to say anything, no matter how harmful or dangerous, because they want that for themselves. And some of them really, really want to be able to say the n-word.

Rogan himself is not making these claims to censorship, but he does not like the public scrutiny and expressed his disdain for people who would hold him accountable in a recent standup comedy performance in Austin, Texas, and in a roundabout way, blamed his victims. “If you’re taking vaccine advice from me, is that really my fault?” he said. “What dumb shit were you about to do when my stupid idea sounded better?”

But Rogan’s suggestion that eleven million people are at fault for taking him seriously is disingenuous. If they did not listen to his stupid ideas, Rogan would not have a $200m deal from Spotify. Whether he chooses to admit it or not, he is responsible for the consequences of what he chooses to say and do.

He also benefits from an accelerated decline of trust in institutions. Americans distrust media, government and corporations more than they ever have, and part of Rogan’s schtick is that he thumbs his nose in the face of authority. His dismissal of expert consensus around Covid is a symptom of this, and it resonates with his audience. For them, he is not representative of institutional media (even though Spotify paid more for his podcast than it did actual full-blown media companies, like the award-winning narrative podcast production house Gimlet Media), he is a check on it – a kind of everyman whose scepticism about anyone who would tell him what to believe makes him enormously relatable.

He can brand himself as an independent thinker, even as his audience appears to exhibit the same cluster of beliefs about what socially acceptable discourse is, and who should be afforded consideration. They are, as critic Harold Rosenberg famously coined, a “herd of independent minds”.

Rogan considers himself a victim in all of this, and in May last year whined that “woke” culture was becoming so powerful that “it’ll eventually get to: straight white men are not allowed to talk”, and this taps into his mostly straight white male audience’s feeling that their power is being attenuated by women and minorities.

And what Rogan and his audience want is not an environment where straight white men are just allowed to talk; they want a world where straight white men are allowed to say anything, and are rewarded for it.

So far, they’re getting what they want. Rogan has faced no penalties from Spotify for what he’s said and done (though they have said they will add Covid-19 content advisories to episodes that discuss the pandemic, and the company is investing over £70m in audio “from historically marginalised groups” to counteract accusations of pandering to racism). There’s no evidence that the bad press has made Rogan less popular. If anything, it’s increased his profile.

This is the resulting reality: the most powerful podcaster in America – a man who sincerely believes the moon landing was faked – is demonstrating in real time that there’s nothing that won’t be tolerated when large amounts of money are involved. For small-time podcasters, much of what Rogan has said and promoted would be career-ruining. But if you’re Joe Rogan, there’s no such thing.

Elizabeth Spiers is a writer and political commentator. She was previously editor-in-chief of The New York Observer