For as far back as I can remember, I have always thought that for Europe to function well as an economic unit, Germany would have to change course. And it looks as though Trump’s cozying up to president Putin, his apathy towards Nato, his insistence on higher defense spending in Europe, and of course, his love of tariffs has finally helped Germany to wake up.

For the past generation, Germany has played an odd role at the heart of the EU. It is the largest populated and most important economic member of the bloc – but its economy is driven by strong exports, alongside persistently weak domestic demand, led by usually subdued consumption and relatively high personal savings – and that doesn’t make a lot of sense.

As we saw during the euro crisis, some countries had been living beyond their means, and they tended to have big persistent imbalances with Germany, which caused a significant weakness to develop at the centre of the eurozone.

Germany enjoyed strong export growth to China and for many years, also Russia. But once the booms in these two economies stopped, Germany’s apparent strength turned out to be a weakness. It was too reliant on exports, and for the fifth largest economy in the world to be so dependent on exports doesn’t make sense – it means you don’t really have control over your own destiny.

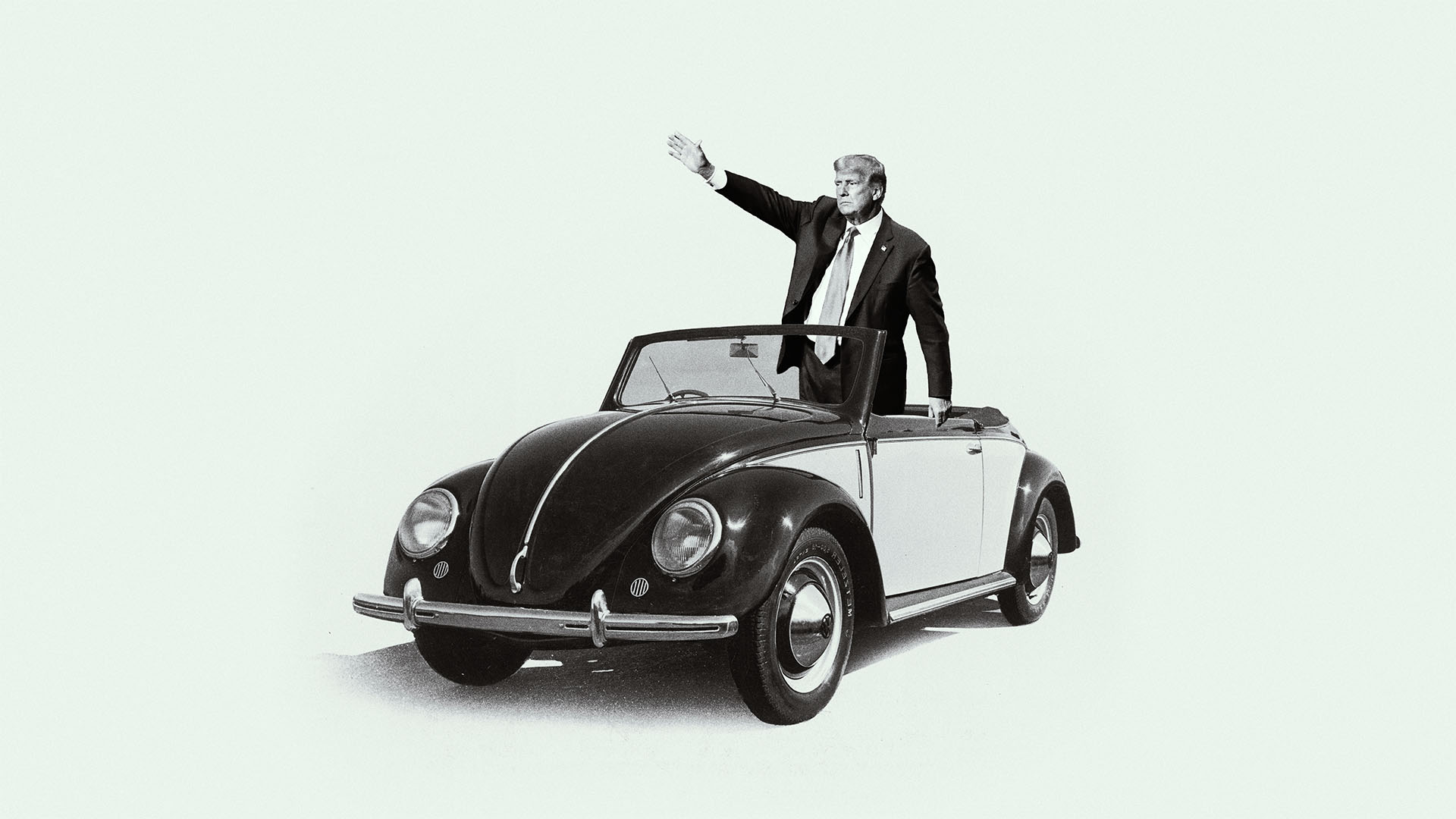

And it looks as though it has taken a combination of Trump’s second term, a collapse in China’s demand for German goods, and the crisis in Ukraine, on top of the general fracturing of Germany’s traditional post war political parties to cause the incoming chancellor, Friedrich Merz, to act.

The shift in defense spending and the changes to the debt limits are both encouraging. While it is hard to believe that the German government will completely turn away from fiscal responsibility, the shift in economic priorities is a huge step. Now, Germany has a good chance of shifting the balance of its economy more towards domestic consumption and, not to be forgotten, domestic public investment.

Given the close link between a country’s domestic spending and its imports, this shift is also likely to benefit Germany’s neighbours, Italy and France in particular. This shift should also encourage the current UK government to improve its post EU-trade relationship with Germany and the rest of the EU. And while a return to the single market in the near future might seem a little fanciful, it’s certainly a more attractive prospect.

All of this has been noticed by the financial markets, and has led to a modest (so far) recovery of the euro against the dollar, and weakness in the US stock markets. This could be the beginning of something more permanent.

Germany has always opposed the introduction of “Euro bonds”, with all EU members carrying the same risk, but I would not be surprised if that position begins to change. If international investors are able to sink money directly into the eurozone, it could become an attractive alternative to the dollar.

As for the US, Trump and his key policymakers appear to accept the fact that their policies are leading to the decline of US stocks, and that tariffs will raise prices on imports, potentially boosting inflation and weakening Americans’ spending power.

As I wrote in my previous article here at the New European, the Trump Administration’s goals are the opposite of Germany’s: to weaken domestic consumption and spending, and raise savings and exports relative to imports. Let’s see whether Trump holds his nerve as the markets weaken, along with his poll rating. But for Europe, it looks like the positive shift is coming, irrespective of what becomes of Trump and his economic plans.