“Sordid,” the New York Times called it, “and sordid is really a mild word for its

pile-up of gross indecencies”, many of which were apparently perpetrated by “a hypnotically ugly new young man who goes by the name of Jean-Paul Belmondo”.

It’s fair to say that Jean-Luc Godard’s 1960 film Á bout de souffle, released in Anglophone countries as Breathless, baffled and fascinated critics in equal

measure; both reactions largely down to the presence on screen of Jean-Paul Belmondo. No one had ever seen anyone quite like him before, meaning that no one really knew what to make of him. One French reviewer wrote that, “his eyes are too small, his mouth is too big, his nose is broken – in short, he is irresistible”.

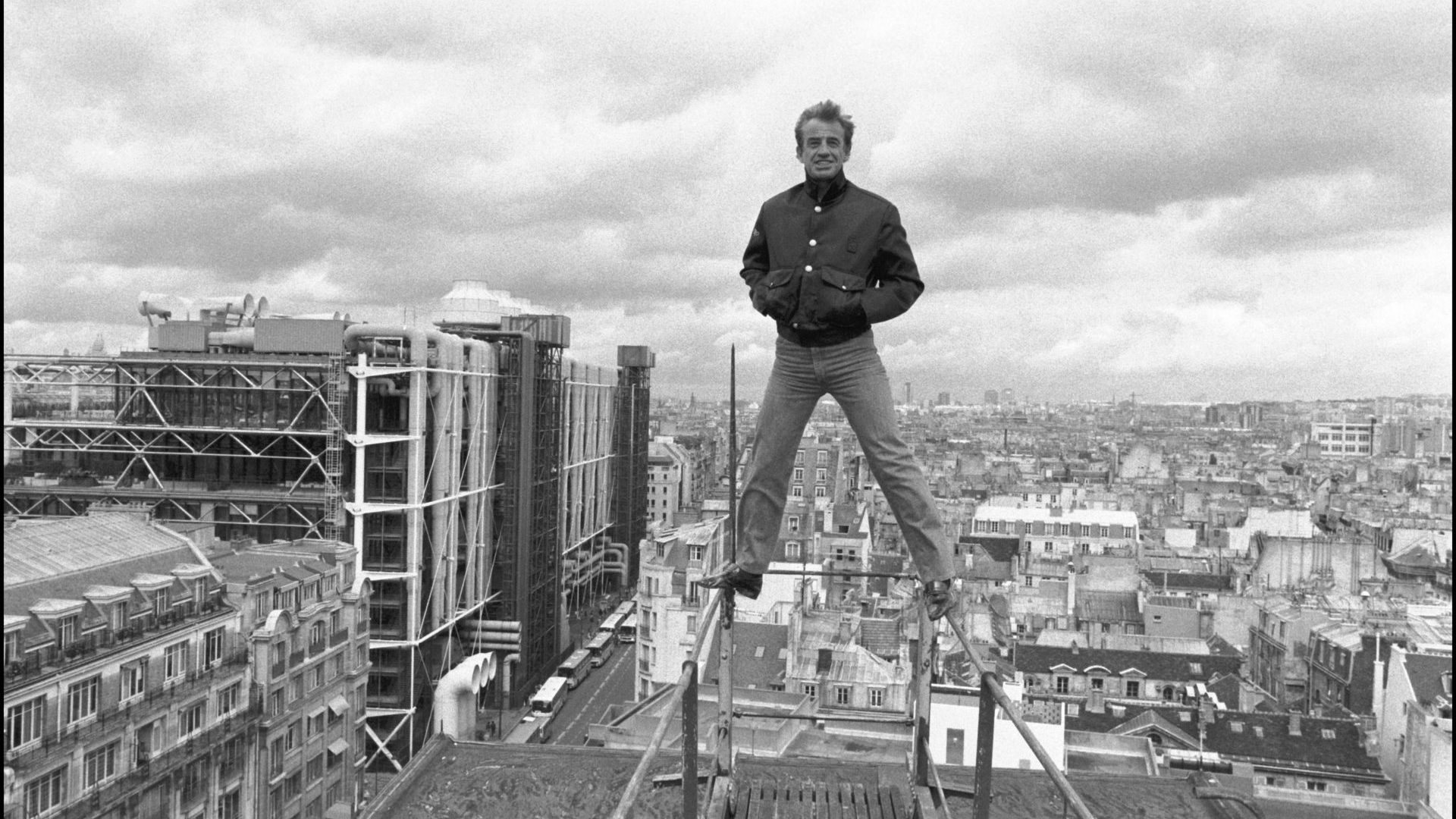

With his oversized lips and flattened, crooked nose – the legacy of a successful amateur boxing career from which he emerged undefeated if not

unscathed – Belmondo cut an unlikely figure for a heartthrob: the white socks, the heavy tweed jacket two sizes too large, the tie worn short with a fat knot, the felt trilby. Put that outfit on most people and you’d assume they’d been messing about in their father’s wardrobe.

But this was Jean-Paul Belmondo. The jacket hung exactly right, the hat was

worn at the perfect angle, a cigarette defied gravity on that plump bottom lip

– somehow, he arranged this unlikely combination to become the absolute

personification of insouciant cool.

Belmondo’s Michel opens the film stealing a car in Marseille and being pursued into a copse by a motorcycle policeman whom he shoots dead with a pistol found in the glove compartment. He drives almost the length of the

country to Paris and is reunited with Patricia, a part-time journalist for and

seller of the New York Herald Tribune, played by Jean Seberg.

Despite being the most wanted man in France, he makes only token attempts to hide himself, walking the streets reading newspapers, making endless telephone calls to people from whom he might be able to extract cash and hanging around Patricia, who eventually betrays him to the police with fatal results.

The plot, based on a true story, does not amount to much but the film is a

cinema classic; the archetype of the nouvelle vague. There are disorientating jump cuts between scenes, the actors wore no make-up, there was no artificial lighting or studio sets and while the dialogue wasn’t entirely improvised it was written mostly on the hoof by director Jean-Luc Godard and fed to the actors during filming.

For all Godard’s vision, it’s Belmondo who makes the film a classic. In the hands of other actors, Michel could just have been a standard, forgettable

B-movie hoodlum, but Belmondo turns him into something far more nuanced and affecting. For one thing, Belmondo is entirely comfortable in his own skin. There’s something in the way he moves that makes his portrayal of the surly yet vulnerable Michel utterly convincing, giving this low-rent, wannabe gangster a wry knowingness while also viewing the world around him through the eyes of a child. At one point, Michel pauses in front of a film poster featuring Humphrey Bogart, taps the glass and murmurs, “Bogey…”, in awe of the cinematic personification of everything he wants to be.

Godard had first seen Belmondo on stage in 1958, in the comedy Un drôle de

dimanche. He cast him in the 12-minute short Charlotte et son Jules, a self-confessed “homage to Cocteau”, in which Belmondo’s character berates his

girlfriend in a hotel room. It wasn’t his first screen appearance as there had

been a handful of small roles, but that role marked the beginning of a remarkable creative collaboration in which Belmondo responded brilliantly to Godard’s ideas and methods.

Their partnership is distilled to perfection in Breathless, the perfect actor for the perfect film at the perfect time. When Seberg reads a line from a William Faulkner novel, “Between grief and nothing, I will take grief”, and Belmondo responds, “Grief is stupid – I choose nothing”, he expresses exactly the kind of youthful nihilism driving the film, with echoes of Marlon Brando’s “whaddaya got?” answer to what he was rebelling against in The Wild One.

Yet, even if Breathless made Belmondo the face of the French new wave, it

wasn’t a role that he either coveted or relished. He worked with Godard again

in 1961’s Une Femme est une Femme and four years later in Pierrot le Fou, and he starred as a priest in Jean-Pierre Melville’s Léon Morin, Prêtre – and in Le Doulos as a thief under suspicion of being a police informant, but he expressed dissatisfaction with being associated so closely with the nouvelle vague. He would claim that he didn’t know what the term meant and confess his boredom with films that were consciously arty, telling one interviewer in the early 1960s that he preferred “making adventure movies to intellectual ones”.

However, although he was cast in a number of more commercial productions – to the end of his life, he rated the rip-roaring 1964 James Bond parody L’Homme de Rio as his favourite – the lure of Hollywood never seduced him. For one thing, Belmondo had absolutely no desire to speak English.

“Why complicate my life?” he shrugged. “I am too stupid to learn the language and it would only be a disaster.”

Belmondo had never really intended to be a screen actor in the first place. The son of a sculptor father born in Algeria to Italian parents and an artist mother, he grew up in Paris and attended France’s prestigious Conservatoire National d’Art Dramatique, graduating in 1956 despite an inherent rebellious streak that put him consistently at odds with the stultifyingly traditional establishment. He once performed an entire Molière play with his hands stuffed in his pockets, rubbing his conservatoire elders up the wrong way but providing a perfect encapsulation of what lay ahead.

He was developing a successful theatre career with the odd pieces of film work between roles when Breathless turned Belmondo into the poster boy of

modern French cinema. Film took over his life for the next two decades and

beyond, but he did return to the stage successfully in the late 1980s, notably

playing a memorable Cyrano de Bergerac in Paris in 1990 and going on to form his own theatre company.

When he suffered a serious stroke in 2001 at the age of 68, it looked as if Belmondo’s career might be over but there was one last leading role to come,

in 2008’s Un Homme et son Chien. By now his hair was white and the famous lips had shrunk almost to nothing, but despite clear physical limitations and

slurred speech Belmondo turned in a hypnotic performance.

In the final scene, as he stands on the track at the mouth of a railway tunnel

watching a train hurtling towards him, he was still somehow the same insouciant man-child he had been more than 40 years earlier, sauntering through the streets of Paris in a sordid pile-up of gross indecencies that changed cinema for ever.