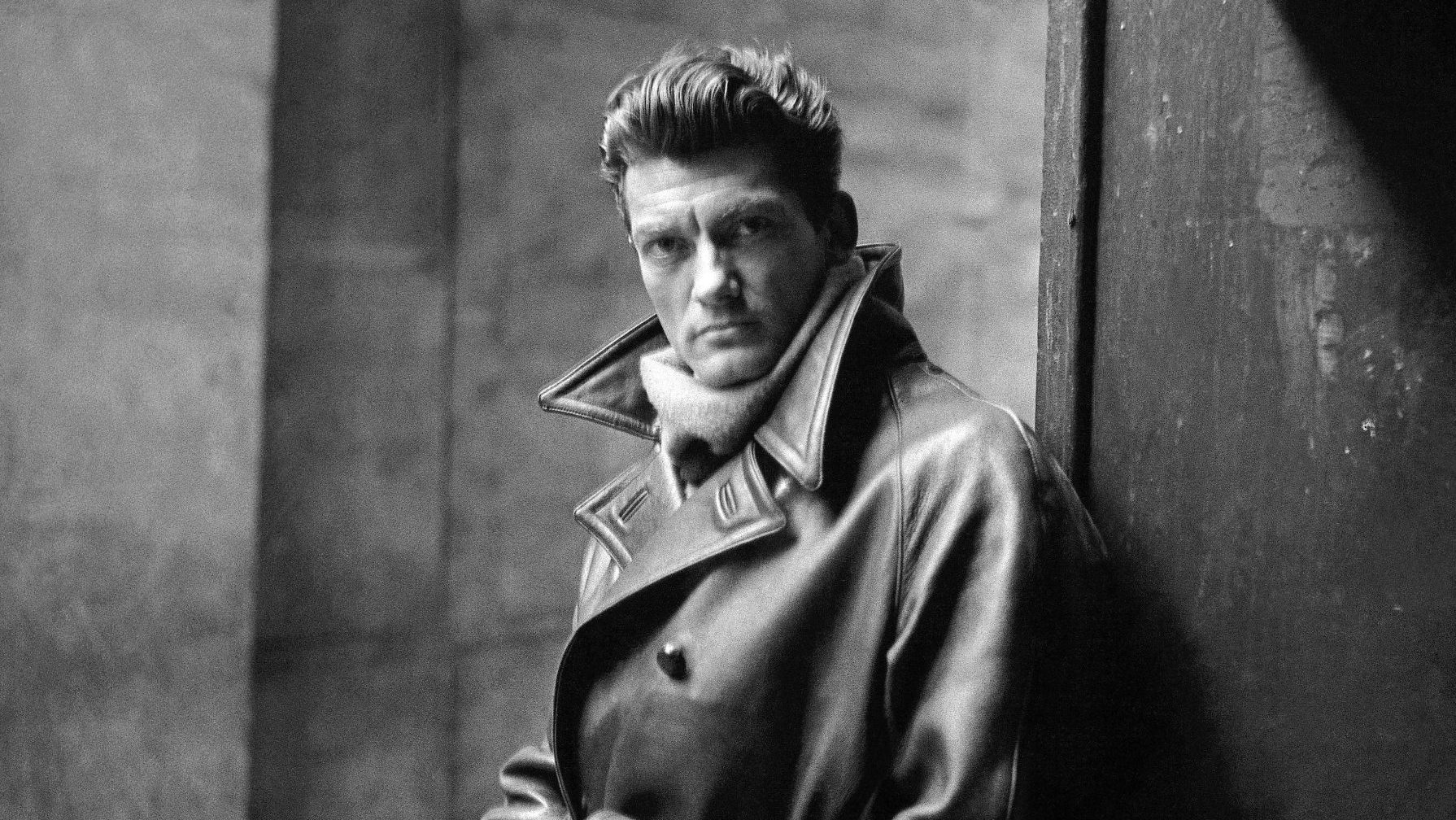

The 24-year-old actor bounded up the stairs two at a time, ran along the corridor and knocked hard on the door of the hotel room. When it opened there stood Jean Cocteau, in a silk dressing gown pockmarked with cigarette burns, the room behind him fogged with opium smoke. The writer-director looked pained but certainly not displeased to see the ruggedly handsome form of Jean Marais looking back at him, breathing heavily from the exertion.

Two weeks had passed since Cocteau disappeared. The production of his Oedipe Roi, an adaptation of the Oedipus story, performed as part of the 1937 Paris Exhibition, had seen audiences noisily registering their displeasure nightly and been savaged by critics.

Cocteau wanted to make a radical casting change. The inexperienced Jean Marais had only a small role but Cocteau had been impressed by his stoicism in the light of rowdy crowds when other members of the company became visibly unsettled. Cocteau tried to replace the lead actor with Marais, something unanimously opposed by the rest of the corps.

Then when Marais quietly asked whether Cocteau might consider him for an understudy role in his forthcoming play Les Chevaliers de la Table Ronde based on the King Arthur stories, Cocteau thought for a moment and announced that, far from an understudy, Marais was his ideal Sir Galahad.

Then Cocteau vanished.

Two weeks later Marais was starting to believe his big opportunity had gone when he received a message from Cocteau summoning him to a hotel immediately. There had been, he said, “a catastrophe”.

“What’s happened?” panted Marais as Cocteau stood aside and indicated he should enter. “What is this catastrophe?”

Cocteau walked to the window and looked out over the Paris rooftops. “There has indeed been a catastrophe,” he sighed, and turned to face Marais. “The catastrophe is that I have fallen in love with you.”

Marais was nonplussed but knew his response to this news could have an enormous bearing on his future career.

“I told him I loved him too,” he recalled in 1997, “even if at the time it was not true. I was an arriviste and could not say no. But before long I was in love with this great poet who was determined to change the insignificant being I was into something special.”

The relationship between Marais and Cocteau would become one of the great romances of 20th-century European culture and would inspire both men to creative heights in film, theatre, poetry, art and sculpture.

“I was born twice,” Marais would say in the years following Cocteau’s death in 1963. “Once on December 11, 1913 and again on the day in 1937 when I met Jean Cocteau for the first time.”

It is fair to say that until he crossed paths with Cocteau, Marais’s career was not exactly blazing a trail through the acting firmament. Born in Cherbourg, he and his older brother Henri moved to Paris with their mother Henriette, a kleptomaniac who endured several spells in prison, when she left their father after the first world war.

Marais had harboured acting ambitions ever since he saw Pearl White in the action-packed 1914 melodrama The Perils of Pauline at the cinema, ambitions that remained undimmed even when he was rejected by a string of Parisian drama schools. Eventually he joined Charles Dullin’s theatre where free acting lessons were available in return for taking small, unpaid parts in house productions.

When a group of fellow students set up a company to produce Cocteau’s Oedipe Roi for the 1937 Paris Exhibition, Marais agreed to join them when he learned that Cocteau, whom he already admired, would be directly involved.

Les Chevaliers de la Table Ronde, featuring Marais as Sir Galahad, opened at Paris’s Theatre de l’Oeuvre in October 1937 but closed just three months later. Critics panned the production with Marais’s acting in particular singled out for criticism, even if they did concede that the handsome actor at least looked the part.

Neither Cocteau nor Marais were deterred, with Cocteau basing his next play Les Parents Terribles on Marais’s close relationship with his mother and casting Marais as the lead. This time the pair combined to create a critical success that would later be adapted for the screen and made Marais’s name in the French capital. Their next collaboration, the 1943 film L’Eternel Retour, based on the story of Tristan and Iseult, made Marais famous across France.

After the liberation, Marais joined a tank regiment as a supply driver, displaying enough courage under fire to be awarded the Croix de Guerre, and when the war was over took the role that made him internationally famous: the Beast in Cocteau’s imaginative adaptation of Beauty and the Beast (La Belle et la Bète) opposite Josette Day.

By then the couple’s relationship had moved from lovers to a close friendship that endured until Cocteau died in 1963.

“It became a friendship that went beyond the boundaries of the physical,” recalled Marais. “He was the only person for whom I would have sacrificed my life.”

In 1983, 20 years after Cocteau’s death, a 70-year-old Marais returned to the stage with his heartfelt one-man show Cocteau-Marais and played to packed houses every night at the L’Atelier, the theatre where he had taken his first acting steps at the Dullin school.

Yet he was far more than just Cocteau’s protege, starring in films by such directors as Sacha Guitry, Jean Renoir, Luchino Visconti, Jacques Demy and Abel Gance. His last significant screen appearance came in 1998 as an elderly art critic in Bernardo Bertolucci’s Tuscan fantasy Stealing Beauty, confirming there was far more to his repertoire than the vigorous muscularity that defined most of his career.

In 1959 at the Gala de l’Union Des Artistes, at which celebrities performed sometimes hair-raising stunts, Marais outstripped everyone by shinning up an 18-metre pole, lighting a cigarette from a gas jet burning at its top, and sliding down again. The director André Hunebelle witnessed the stunt, leading to a lead role in the swashbuckling adventure Le Bossu and a string of physically demanding roles in which Marais, despite the onset of middle age, insisted on doing his own stunts.

“He did amazing things on the screen but he never trained for them,” said Jean-Paul Belmondo of Marais’ autodidactic development as an actor.

“I just always wanted to be happy,” Marais told Le Figaro a few months before he died. “Perhaps that’s what pleased Cocteau, who was so anguished, yet I have never known stress. I was a sort of beast, a peasant type. I had no culture. I was given an unbelievable chance.”