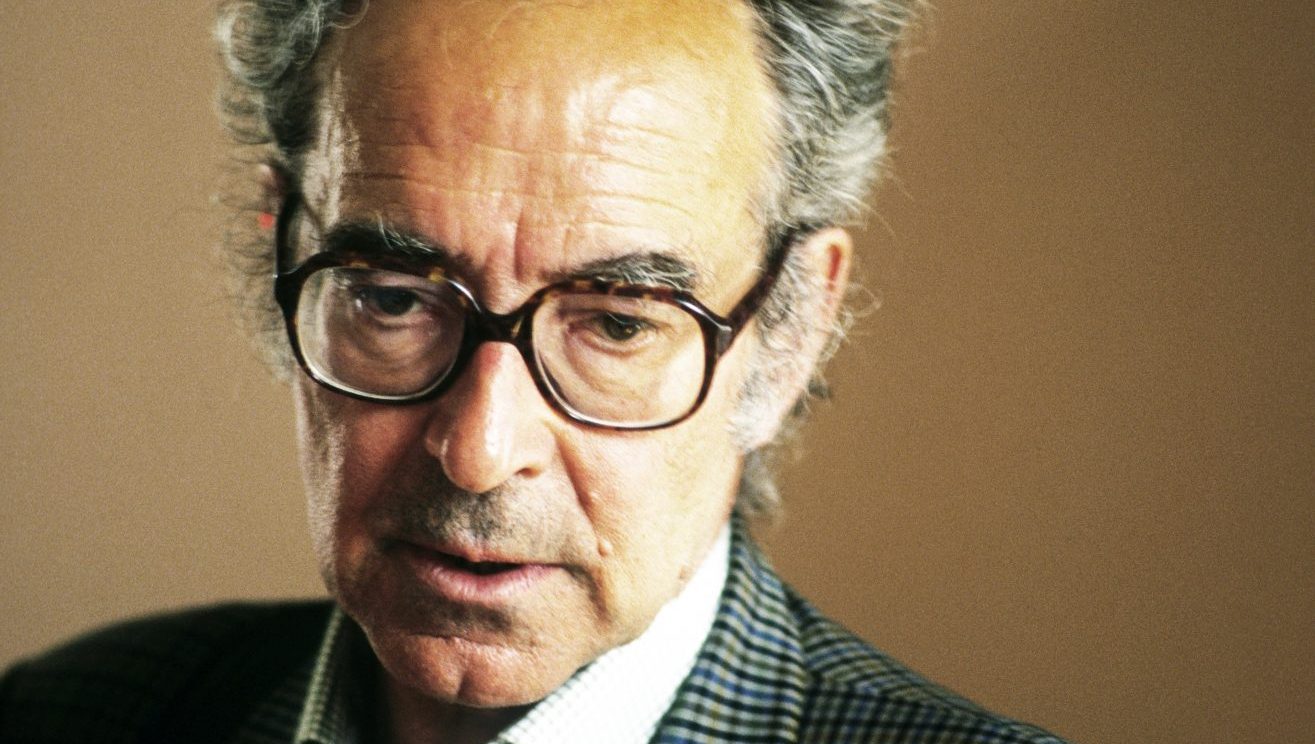

It was a drizzly Friday night in London at the end of November 1968 and Jean-Luc Godard was walking fast along the South Bank, incandescent with rage.

Behind him One Plus One, his documentary shadowing the Rolling Stones as they recorded Sympathy for the Devil, was receiving its premiere at the National Film Theatre as part of the London Film Festival, but its director was not there.

Indeed, if it was down to him the film would not be showing at all. To his fury, the producer, Iain Quarrier, had not only changed the title to Sympathy for the Devil, he had added a full version of the song to the end of the film, something Godard had deliberately avoided.

Godard replayed in his mind the events of the previous few minutes. Once the audience had settled, Godard walked on to the stage and begged them not to watch Quarrier’s version. He asked them instead to return to the foyer, obtain refunds and donate them to the Eldridge Cleaver Defence Fund in aid of the Black Panther leader’s fight against murder charges in the US.

The crowd shifted, unsure whether he was serious. When he asked for a show of hands in support of abandoning the premiere not a single one went up. There were nervous titters as Godard glared around the auditorium before the mood darkened. A voice from the back informed the director he had “a bloody cheek”. Another called him a “pompous bore”; someone else piped up “just show us the film or get out”.

When Quarrier then walked on to the stage to reason with Godard the director punched him in the mouth, roared “you are all bourgeois fascists” and was wrestled from the stage and out through the doors by cinema staff.

Thundering along beside the shifting lights of the city on the black surface of the Thames, Godard registered briefly a flickering light coming from beneath one of the nearby railway arches: some film students had organised an al fresco screening of his original version beamed on to the brickwork.

1968 had been a tumultuous year across the globe, and was proving to be a watershed for Godard. Hailed as an innovator of unprecedented cinematic vision after the success of his 1960 debut Á Bout de Souffle (Breathless), he had been at the forefront of the 20th century’s most exhilarating cultural revolution ever since.

Á Bout de Souffle was as fresh and cool as anything ever committed to celluloid, from Jean Seberg’s crop to the realist style with its jerky cuts and reliance on natural light. This was fiction as reportage, shot cheaply and quickly, almost guerilla in creation, injecting raw freshness into a stale medium, albeit with a sometimes baffling narrative. Godard recalled a quip he’d made at a 1962 Cannes symposium when Georges Franju harrumphed “films should have a beginning, a middle and an end” and he had replied, “ah, but not necessarily in that order”.

He relished each project with its opportunity for reinvention, presenting a new challenge each time. Even the notoriously hard-to-please Pauline Kael, critic for the New Yorker, had called him “the most exciting director working in movies today” and said “the corpses of his imitators littered the world’s film festivals”.

By 1968, however, his momentum seemed to be stalling. A new generation was emerging, Quarrier’s alterations suggested he was not as untouchable as he once was, and his sense of artistic identity had been challenged for the first time in his career.

Something was changing. Maybe everything was changing. Earlier that year he had led protests against the dismissal of Henri Langlois, founder and head of the French film repository Cinémathèque Française. Godard and other directors from the nouvelle vague even succeeded in closing down that year’s Cannes Film Festival, stoking a nationwide rebellious discontent that fired the May 1968 demonstrations.

One of the slogans from the spring riots came back to him: “L’art est mort. Godard n’y pourra rien”, (“Art is dead. Godard can do nothing”). Could that be true? At the end of his 1967 film Weekend the word Fin had appeared on the screen, signalling the end of the film in the traditional manner. Godard then added the words “de cinéma”, “the end of cinema”. Did he really believe that? Perhaps. It certainly felt appropriate at the time, but was it now coming back to haunt him?

He stopped walking and looked down at the river detritus undulating against the bank beneath the lights of the city. He was right. He knew he was right. He was right about Quarrier, right to believe the premiere should have been stopped. If his career so far had taught him anything, it was to trust his convictions, to embrace his instincts. Á Bout de Souffle was only the second time he had been behind the camera after all, and only a year after the first – a short documentary about the construction of the Swiss dam his parents had made him work on after his kleptomania made it pertinent to leave Paris for a while.

By then he had almost a decade of immersion in film, from binge-watching at Langlois’s Cinémathèque Française to working in a studio press office to writing reviews for the seminal Cahiers du Cinéma. He knew what cinema needed and knew he had the vision to make it happen.

And he did make it happen. Because it was simple. Cinema was life. That’s what idiots like Quarrier didn’t understand and that’s what he had said in the telegram he’d sent pulling out of a lecture at the NFT a month earlier. What could he possibly impart that was not already up there on the screen?

“If I am not there, take anyone off the street, if possible the poorest,” a member of staff read out to the sold-out audience. “Give him my fee and talk with him of images and sounds and you will learn much more than from me because it is the poor people who really invented the language.”

That was all that mattered, he mused as the rain ran down his face. That’s what it came down to, that’s what he was doing with every film: the conflation of life itself with cinema.

He looked up at the night sky, watching the rain drops appear like tiny falling stars out of the blackness into the light. He would show them, he vowed. Not only that, he would keep showing them for as long as he lived. This was his life, and cinema was life.