With a taste for graffiti, and the daring to use a burnt-out car as raw material, Jean Dubuffet feels like an urbanite. But it was the astonishing change he saw on returning to Paris after six years in the south of France that helped create some of his best work.

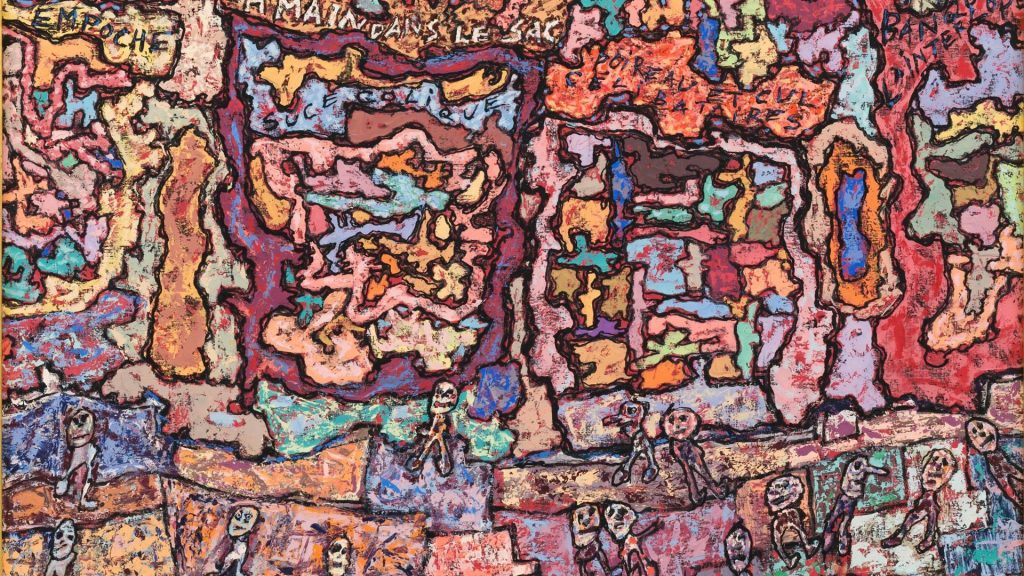

Busier streets and a disreputable undercurrent run through the French capital he records in La main dans le sac (Caught in the Act), painted in 1961 as part of his Paris Circus series. With every bit of the canvas restlessly filled, the picture is a visual gasp at the dodgy businesses, power-walking pedestrians and determined drivers, everyone intent on their own destination.

Today the picture lives in the Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, but it is on loan to the Barbican Art Gallery in London, where a landmark exhibition of work by Dubuffet, entitled Jean Dubuffet: Brutal Beauty, has been helping another capital city get back into the swing.

Perhaps some of those driven Parisians are on their way to a businesslike dining room on the Boulevard de Montparnasse, to join row upon row of diners. Some of those at table in the art nouveau Restaurant Rougeot, also depicted in 1961, have a blob of food on their plates, others watch the approaching waiting staff expectantly. Today known as the Bistro de la Gare, this is an eating factory.

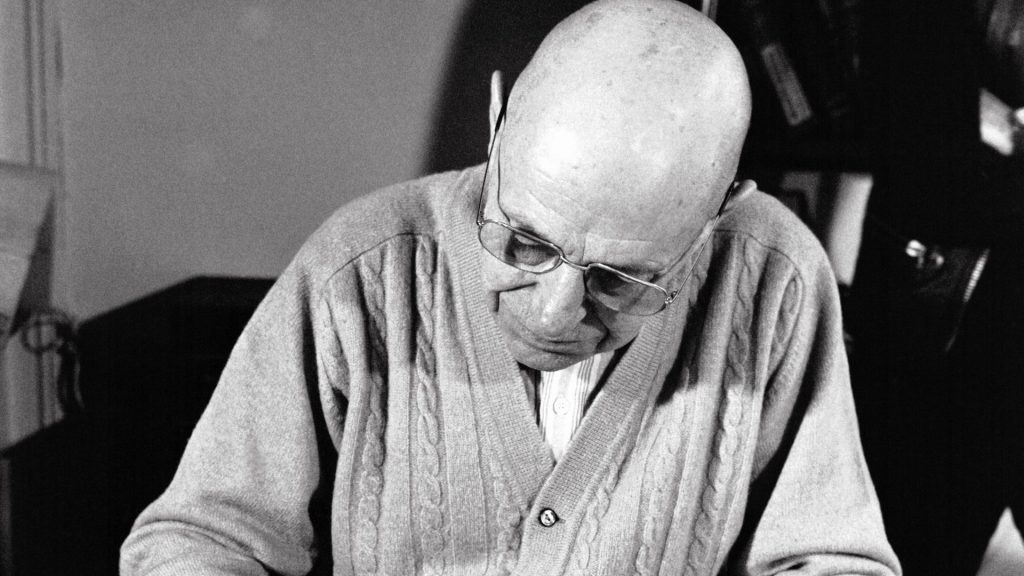

The childlike faces of Dubuffet’s diners – childlike both in features and in execution – are the result of years of the artist’s experiments going against the tide in art. A late arrival on the art scene – for many years he ran the lucrative family wine business – he nonetheless had his heart set on an artistic career.

Born in Le Havre in 1901, by the age of eight he had opened a museum of found objects in his wardrobe, and at 18 he had both joined and left the prestigious Académie Julian in Paris, disillusioned by the teaching, which he considered superficial.

“I became convinced that artistic creation had to be anchored in everyday life,” he wrote. “The black hat was replaced by the populist cap.” He hung around Montmartre, befriending artists including Suzanne Valadon and her son, Maurice Utrillo, and in time falling in with the influential dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler and, from his roster of artists, Juan Gris and Fernand Léger.

It was while on military service in 1923 at the Met Office, stationed in the Eiffel Tower, that Dubuffet came across a sketchbook of imaginary scenes and mystical cloud formations that informed his own fantastical vision. On discovering the excitingly uninhibited artworks of psychiatric patients, he doubted his own ability. He stopped painting and soon joined the family business, which would have foundered in the late 1930s but for the outbreak of war which put everything on hold.

His growing interest in art by untrained hands increased with the discovery in 1940 of the dynamic Paleolithic murals at Lascaux in the Dordogne, a revelation that made many artists reconsider their method. Dubuffet was looking anew at materials, favouring the coarse over the refined, for texture and vitality.

The moon-faced characters dining so neatly in the Restaurant Rougeot were born out of portraits made immediately after the second world war, the features stripped back to their most basic form, with eyes like peas and tombstone teeth. “Funny noses, big mouths, crooked teeth, hairy ears,” he wrote. “I’m not against all that.”

In the 1950s he challenged another artistic convention, with a series of female nudes unlike anything that had gone before. In place of the idealised form, he found a new reality in women’s figures that are swollen and flattened, massively solid and also running with fluids. To create these ambiguous forms he once again harnessed materials differently. Starting with a thick zinc oxide paste and varnish, to suggest the solidity and sheen of flesh, he then applied oil which was repelled erratically, creating rivers of paint.

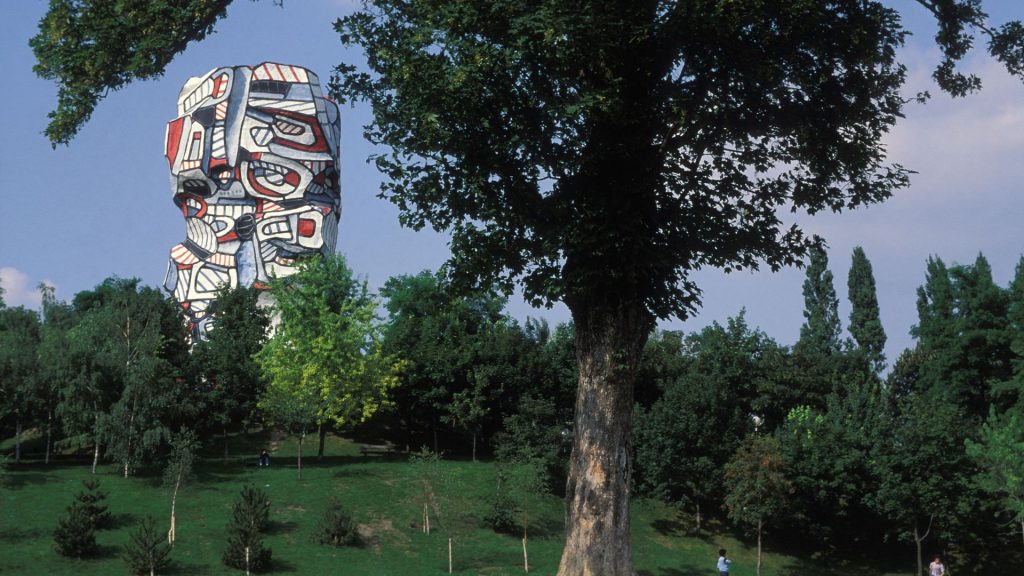

Sometimes his own work became a raw material, as in Coursegoules (1958), for which he cut up paintings and arranged the fragments to create a new image. From here it was a short step in a long career to his similarly fragmentary invention, L’Hourloupe – cheerful and complex meanderings that can be traced back to absent-minded doodles with a ballpoint pen. Armed in the 1960s with a new-fangled gadget that offered four colours in one stylus, he turned his back on natural shades and experimented with bright red, blue, black and white only, drawing irregular and interconnecting shapes, infilling them in turn with blocks of colour and grids both tight and airy.

In time these primary-coloured mini-universes took on three dimensions with the bravura multimedia Coucou Bazaar, a theatrical, dance and music experience staged in New York in 1973. Revised in Paris, Dubuffet was dissatisfied with the choreography for his costumed figures and pieces rolled on casters.

But turn a corner at the Barbican Gallery and you can relive something of that anything-goes experiment. Music played an important part in the life of the artist, who jammed on the piano and other instruments in his own make-shift recording studio with the Danish painter Asger Jorn. The two were natural allies, Jorn a founder member of the CoBrA (Copenhagen/Brussels/Amsterdam) group who, like Dubuffet, found post-war truth in simple, childlike forms.

After this larger-than-life creation, and as back problems obliged him to sit at a desk, the artist began to work on a smaller scale. By the early 1980s came the ultimate refinement, a series called Mires. Here he abandoned the figure altogether and focused on the dynamics between energetic marks and lines that race across black grounds, the reds and blues of his Hourloupes day taking on wilder and less contained roles.

In January 1983, at the age of 83, Dubuffet received a commission from the French government. In the February and March he hurriedly wrote the story of his life, Biographie a pas de course (Biography at a Sprint). Two months later he died at his desk.

President François Mitterand unveiled the commission, Tour aux figures (Tower with Figures) on the Île Saint-Germain in the river Seine in 1988. A massive 24-metre high Hourloupe stack, it commemorates the prolific and endlessly inventive artist on an appropriately gigantic scale.

Jean Dubuffet: Brutal Beauty, Barbican Art Gallery, London until August 22

ART BRUT

On a visit to Switzerland in 1945, Dubuffet connected with the artistic and medical communities and began to collect work by amateur, self-taught artists, often those with mental health challenges or physical disabilities.

He defined Art Brut as “pieces of work executed by people untouched by artistic culture in which therefore mimicry, contrary to what happens in intellectuals, plays little or no part, so that their authors draw everything (subjects, choice of materials employed, means of transposition, rhythms, ways of writing, etc.) from their own depths and not from clichés of classical art or art that is fashionable.”

By 1947, some of the art was on show at the Foyer de l’Art Brut in the basement of the Galerie Drouin in Paris. The collection moved between Paris and East Hampton, USA, with work often shown in a spirit of privacy or for academics only. Finally, in 1967, The City of Paris Museum of Decorative Arts presented a large-scale Art Brut exhibition featuring 700 works by 75 creators.

Four years later, Dubuffet owned 5,000 works by 133 artists. He donated it to the city of Lausanne, where the Art Brut museum at the Château de Beaulieu on Avenue Bergières opened in 1976. It now owns 30,000 works.