Even if he had never made a piece of avant-garde art in his life, Jean Arp’s attempt to avoid the draft in Zurich in 1915 would have still gone down as one of the great Dada moments.

He had moved to the Swiss city from Paris, partly because being officially a German national, things were a little uncomfortable in the French capital –

he had been briefly arrested as a suspected spy – but mainly in order to capitalise on its neutrality. When he went to register with the German consulate, however, he was taking no chances.

On arrival he genuflected in front of a portrait of the German army’s chief of

staff, Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, a pastiche of pious devotion repeated several times during his visit. Handed a form, he filled in every section with his date of birth, drew a line at the bottom, ran his finger

down the list of numbers, raised his eyes to the ceiling while moving his lips

as if making a calculation, wrote a random selection of numbers beneath the line and earnestly slid the piece of paper back across the desk.

The consular official looked at the form, looked at Arp, looked back at the form, picked up a pen and made a note that he should never be considered for military service. The artist stood up, bowed, turned to the portrait, crossed himself one last time, and left.

Arp’s brief encounter with wartime bureaucracy makes for a funny story but is also indicative of a wider picture. The quiet subversion, the tweaking of the nose of normality: in this as well as in his art, Arp was deceptively innovative and unobtrusively influential. That’s why he was an important early leader of the Dadaist movement and would go on to influence the surrealists who followed.

By the time of his bureaucratic encounter in Zurich, Arp was on the way to becoming a key figure in the European art world. He had begun creating abstract art around 1910, and in 1912 travelled to Munich to track down Wassily Kandinsky, who recognised Arp’s talent and organised for him to exhibit with the expressionist Der Blaue Reiter group he had founded. Later that year he was part of a major exhibition in Zurich alongside Kandinsky, Matisse and Robert Delaunay and came under the wing of the influential avant-garde art dealer and publisher Herwarth Walden.

When war broke out Arp was in Cologne visiting Max Ernst, forcing him to act fast to catch one of the last trains out of Germany for Paris, a journey that

in some ways exemplified the paradox of identity underpinning his life.

He was born Hans Peter Wilhelm Arp to a German father and a French mother in Strasbourg, the main city of Alsace, one of the great political footballs of 19th- and early 20th-century European history.

At the time of Arp’s birth, the region had been ceded to the German empire

by the French in the Treaty of Frankfurt after the Franco-Prussian war of 1871. He grew up speaking the Alsatian language, became fluent in French and German (going on to write reams of poetry in both languages), before studying art at the Académie Julian in Paris and the Kunstschule in Weimar.

When Alsace was returned to France at the end of the first world war, French law required he be known as Jean, meaning he spent the rest of his life as Jean to French speakers and Hans to German speakers.

It would be easy to conclude that this schism at the core of his identity produced an internal conflict that fired his creativity. In fact, the opposite was true: he was the living embodiment of the absurdity of borders and barriers. In his artistic output he blurred the boundaries of style and genre, writing poetry as good as his art, making sculptures as good as his collages.

When his two nationalities went to war, Switzerland was the obvious destination, a place of calm among the chaos, a neutral space to create art that was far from neutral, where he could fuse together the release of unconscious perception and the natural world to produce ground-breaking work.

In December 1915 he exhibited a selection of abstract paintings, drawings and sculpture at the Tanner Gallery in Zurich. It was an early attempt to wrest back control of language and art debased by the rhetoric of the war with its propagandic sloganeering and breast-beating recruitment posters and an art world he regarded as creatively hamstrung by enforced ideas of form and technique. Recalling the art classes endured at school, he described how “the everlasting copying of stuffed birds and withered flowers not only poisoned drawing for me, but destroyed my taste for artistic activity of any kind.”

From that Zurich exhibition onwards Arp presented work he regarded as a reset, a bold reinvention that discarded all accepted perceptions, methods and techniques.

He saw more in objects “arranged according to the law of chance, rudimentary, irrational, mutilated” than what hung in the galleries of Europe. He found artistic magic in the way the pieces of torn-up paper fell at random, and more artistic merit in a random sentence excised from an advertisement in a newspaper than in the entire canon of the great poets.

“Dada aimed to destroy the rational deceptions of man and recover the natural and irrational order,” he wrote, a manifesto to which he adhered for his entire career.

Random it may have seemed, but Arp’s work was also supremely eloquent. His 1936 piece Mutilé et Apatride, “Mutilated and Stateless”, was a papier-mache creation from old newspaper that from some angles resembled the head of a figure with its hands placed together, either in prayer or pleading, an evocative representation of the refugee experience in 1930s Europe whose title was a headline visible on the crumpled newspaper.

This was art that had things to say despite appearing to have been created by accident.

In his partner Sophie Taeuber, whom he met at that first Zurich exhibition,

he found his creative inspiration and equal. They lived at Clamart, outside

Paris on the edge of a forest in a house designed by Taeuber, where they

entertained the likes of Joan Miró and Marcel Duchamp. Until her death in

1943 from accidental carbon monoxide poisoning, the couple comprised one

of the most important artistic units in the history of the avant garde, crucial

and mutual pioneers of Dadaism and surrealism.

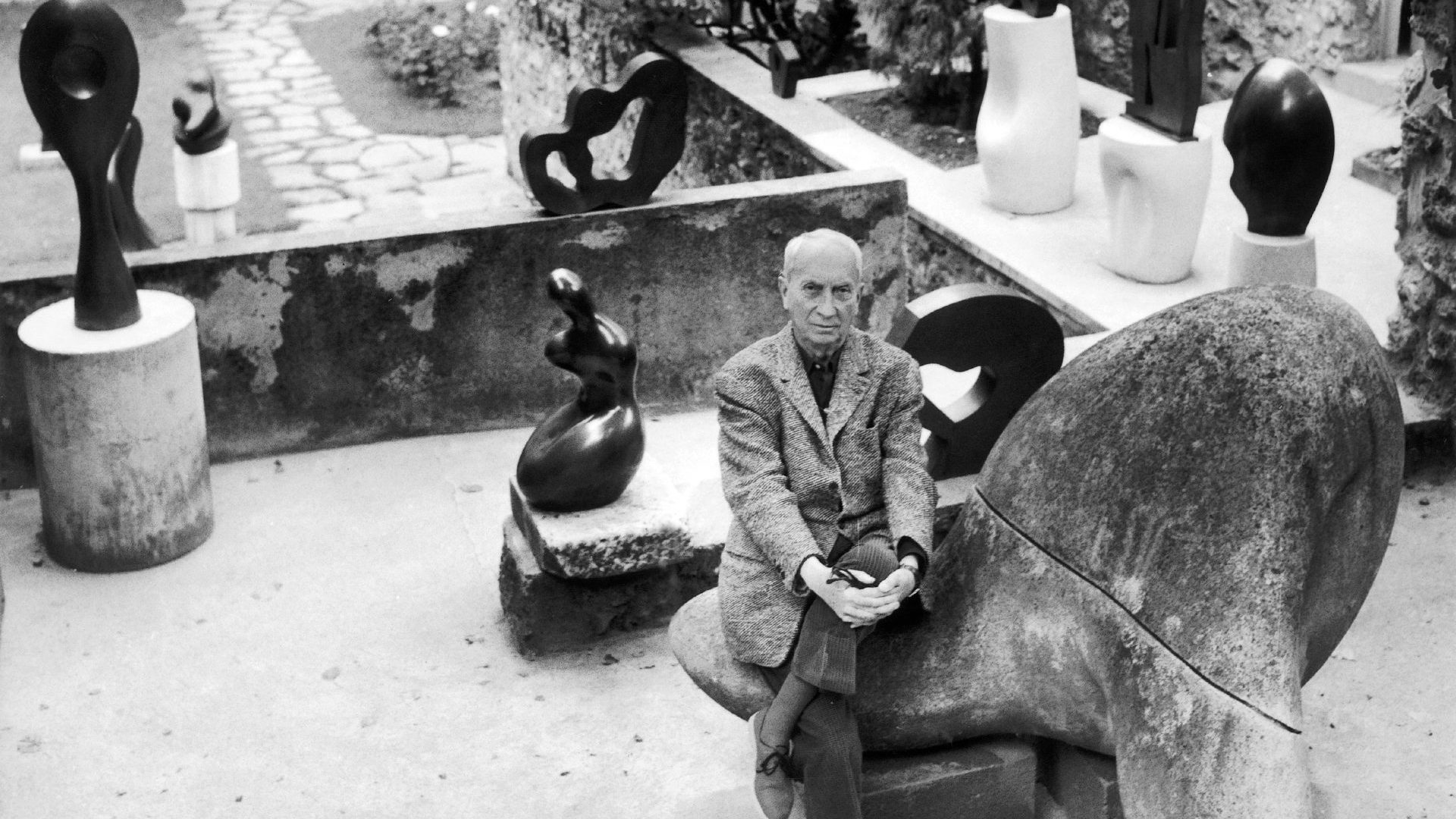

Modigliani painted his portrait, he was a friend of Picasso, James Joyce visited him at home. He directly influenced artists from Jackson Pollock to Barbara Hepworth with his lightness of touch, modesty of concept and almost carefree sense of creation. He was a vital part of early 20th-century European culture, simultaneously on the periphery yet somehow at the centre of a creative world that changed everything.

“I don’t reflect,” he said in 1963. “The forms come, pleasing or strange. They’re born of themselves; I only have to move my hands. The forms that then take shape offer access to mysteries and reveal to us the profound sources of life.”