Just as great football managers create teams in their own likeness, film directors make movies that somehow reflect themselves.

I’d seen the fascinating, dense, complex, brilliant, astounding, wholly eccentric “jazz ’n’ cold war politics” documentary Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat before having coffee with its maker, Belgian multimedia artist and “radical gardener” Johan Grimonprez.

But after only a few minutes in his company, I could see exactly why the film is unique and as provocative as it is. Whatever, it all adds up to one of the best films I’ve seen this year and was among the five best documentary and 12 best film nominees at the European Film Awards in Lucerne last weekend.

Only a short way through the interview, as he departs on a digression about the CIA and Mossad’s role in smuggling Nikita Khrushchev’s memoirs out of Russia, I do have to stop and tell him that while it’s normal for a film-maker to be completely obsessed by their own projects, he seems possessed by this one.

“I’m worried,” I say, “that people might think you’re crazy, you know?”

He pauses. “They say I’m a conspiracy nut,” he smiles. “But I’m not, because I can provide page numbers for all my sources. And if they want to think I’m crazy, I don’t mind. I do seem to go off on a tangent all the time but really I’m just trying to find the truth.”

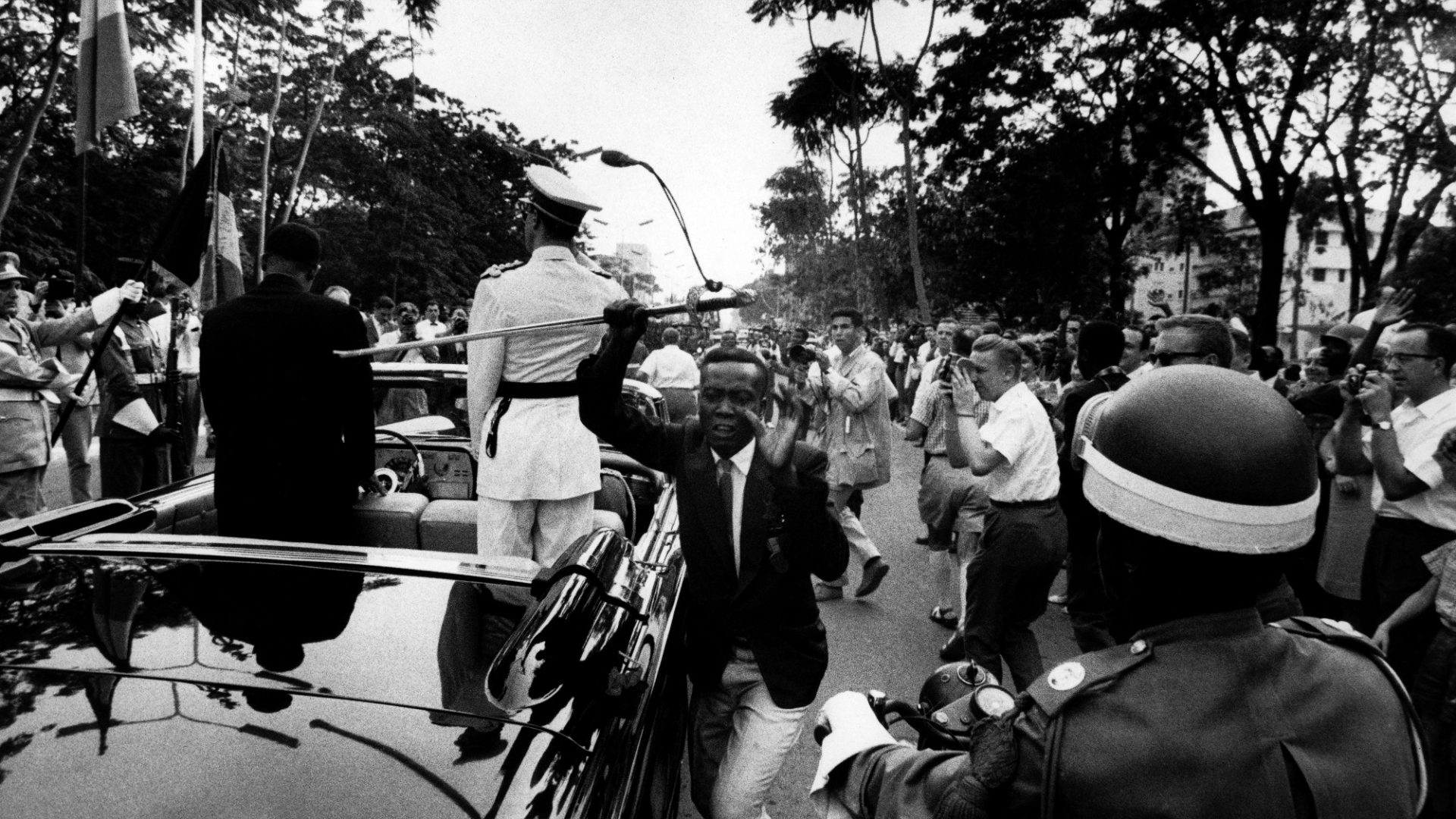

The truth, in the case of Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat, lies in showing how the US government, the CIA and the Belgian authorities used a 1961 African tour by trumpet legend Louis Armstrong as jazz ambassador, to cover up the assassination – the first post-colonial coup, indeed – of the new, democratically elected Congolese president Patrice Lumumba just weeks after the African nation gained independence.

Coming at you as a collage of news clips and voiceovers, of talking heads and jazz performances mixed with archival footage and some startling, almost subliminal flashes, the film touches on many subjects to make its point about colonialism. I asked him how he went around pitching it. According to Grimonprez: “It’s about the promise of decolonisation, the hope of the non-aligned movement and the dream of self-determination. It is also about the multinational corporations working hand-in-glove with the military-industrial complex to smother this dream.”

I can just see the facial expressions on the money people in the room. Passionate, excitable and free-associating at all times, to be honest, Grimonprez perhaps isn’t the best salesman for the hypnotic brilliance of his own film.

He quickly gets bogged down in the stuff he couldn’t show you, the archive he’s dug up implicating this Belgian 1960s political figure and that CIA operative, and the CEO of the mining corporation (Union Minière) protecting the interests of the mineral-rich region of Katanga, particularly its uranium deposits, which had been used to build the atomic bombs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and which the US were determined to keep out of Russian hands as the cold war took an icy turn amid the Pan-African movement.

A lot of the action in this doc takes place at the UN in New York, around the dramatic anti-colonial speeches of Nikita Khrushchev, who comes across as a colourful, shoe-banging, table thumping showman. “His shoes didn’t fit so he went out and bought some sandals,” explains Grimonprez.

Global geopolitics and the Afro-Asian voting bloc meet 1960s American counter-culture when jazz singer Abbey Lincoln and her husband drummer Max Roach crash a UN security council meeting to protest the US-led coup against Lumumba.

It’s absolutely riveting stuff, with footage of 1960s Harlem, the Congo, Eisenhower, Malcolm X and Che Guevara, mercenary soldiers and warfare all intercut with extraordinary jazz concerts unearthed from the Belgian TV vaults of artists including Archie Shepp, John Coltrane, Nina Simone and Charles Mingus. The sounds, textures and energy of free jazz suits the archival-collage style of what Grimonprez’s images and clips are building up, and the effect is, well, dizzier than Gillespie.

To be transparent, this is so up my street as to have moved in next door, although I’m not sure the other neighbours – or my wife – would take so kindly to some of its free jazz moments. Sometimes, I tell Johan, you see a film and you think: did they make this movie just for me? “Of course I did,” he laughs. “I hope you liked it.

“There are 52 tracks here and I’m still trying to clear them all, so it’s been difficult. But the music is so entwined with the politics, the deeper I got into the brief time of Lumumba, the more I saw how jazz was the connecting vibe. For me the music is the flipside, the cover up of a genocide that was going on in east Congo – on Belgian TV they showed these jazz artists, they showed Abbey Lincoln screaming. But it was really there to distract the audience from what was really going on. But you can be sure her scream is a rage, a protest, if you put it in the right context.”

Lincoln’s scream, part of the famous Freedom Now Suite made with Max Roach in 1960, bookends the film, a howl of protest that captures the civil unrest of the time, yet also the spirit of resistance that was blowing through on the wind of Pan-Africanism, when as many as 15 newly independent countries joined the United Nations.

Belgium’s colonial activity centred on the Congo, Rwanda and Burundi, as commanded by King Leopold II, who undertook the Congo as his own private colonial project and ruled by his own private army, the Force Publique. Despite never once visiting the place, he extracted a fortune from it (initially in ivory and rubber) and wrought untold damage on its people, in the form of forced labour, torture, murder and amputations.

The term “crimes against humanity” was coined, in 1890, to describe Leopold’s administration of the Congo. And Conrad’s 1899 title Heart of Darkness still retains its power.

Grimonprez’s film doesn’t need to go into these details, although he does reference Adam Hochschild’s vital 1998 book King Leopold’s Ghost as we talk about the legacy.

“In Belgium, there are still so many remnants of those dinosaurs, and the people behind all the machinations against the idea of a United States of Africa. I’m Belgian, so I grew up with all the Congo images, but with the denial of what was going on, the ‘Empire de Silence’ it was called, until that book, nobody talked about it.

“They just admired the many statues. And there are so many statues.”

Grimonprez says that although it is now fashionable to throw balloons of red paint at Leopold statues and to talk of reparations and repatriation of stolen artefacts, this is again just a distraction from what is really going on still in the DRC, in terms of mineral exploitation and mass rape.

Watching his film, you get wrapped up in the scarcely believable machinations of the moves to control and quash Lumumba and replace him with the “puppet” Mobutu. But there are flashes where you also think you’ve suddenly gone to a commercial break, or that the screen has crashed.

Adverts for iPhone and Tesla flicker briefly before fading away, like glitches. These are oblique references to the modern exploitation of DRC resources such as the so-called “conflict minerals” including coltan, which goes into phone and car batteries.

Grimonprez says there’s a direct correlation between the mining industry and the use of rape as a weapon of war by private militia, including M23 rebels.

“I put an iPhone alarm in there. It’s not subtle at all, because it’s literally a wake-up call. You know, this is still going on.”

He continues, sewing words such as kleptocracy and corporatocracy, conglomerates and astroturfing into the conversation, the companies including Halliburton and Amazon that “exist on clouds floating above the law and beyond taxes, and acting as nation states.” All this he sees as stemming from the cold war manipulation of Lumumba, who “would have been a Mandela”.

When Belgium handed over the Congo, Lumumba was not invited to the ceremony but turned up and made a speech absolutely holding the Belgians to rights over their colonial abuses. Somehow, despite the truth of it, to hear it in the faux-genteel ceremonial context, it’s shocking, devil-may-care politics that got him killed only a couple of months later, all while black jazzmen whitewashed America’s image.

Grimonprez’s documentary competes at the European Film Awards alongside Mati Diop’s Berlin-winning Dahomey, a haunting documentary about the return, from Paris, of 26 statues to Benin, so the issue of reparations and colonial guilt features prominently this year.

The film-maker tells me a story of Lumumba’s gold teeth which were stolen from his dead body following his assassination by mercenaries before his body was dissolved in acid.

“There was a man from the Belgian Army who ended up a schoolteacher in Bruges, who used to boast about this tooth and show it to his class. I know this, because I have a friend who went to that school,” he says. “And last year, the Belgian government made a whole ceremony of sending back these gold teeth in a little coffin, and delivering them to Lumumba’s daughter, Juliana.

“Can you imagine that? Juliana, who told them straight: ‘You didn’t just kill my dad, you killed the dream of an entire continent.’

“To obsess over Leopold II is just nostalgia,” he continues. “We have a wonderful Africa Museum in Brussels and we’re sort of proud of it. That’s just wrong, no?

“But to apologise for history is to ignore the continuation of what’s going on now. It’s not just statues and treasures that have been stolen from the Congo because you can’t give back a history.

“The soul and the dream and any sense of respect has been stolen by Belgium. And that’s why I show Abbey Lincoln’s scream. There are no words for it, because what else can you say?”

Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat is in selected UK cinemas and streams on BFI Player from December 20. The actual soundtrack to Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat is available as a playlist on Spotify. On a phone powered by a mineral likely to have been mined in the Democratic Republic of Congo.