Harold “Kim” Philby was probably recruited by Soviet intelligence in 1934. He joined the British secret services during the second world war, and by 1949 had risen to become the first secretary at the British embassy in Washington. That meant that Philby, the most important figure in the US-UK intelligence relationship, was a KGB plant.

He was eventually unmasked in 1963 and the shock was tremendous, not least within Britain’s intelligence agencies, which had to confront not only their failure to spot the enemy agent, but also the knowledge that if Philby was a spy, everyone was suspect. This was the atmosphere that overshadowed the novelist John Le Carré’s time in the secret service, and that gave his books their dark, paranoiac tone.

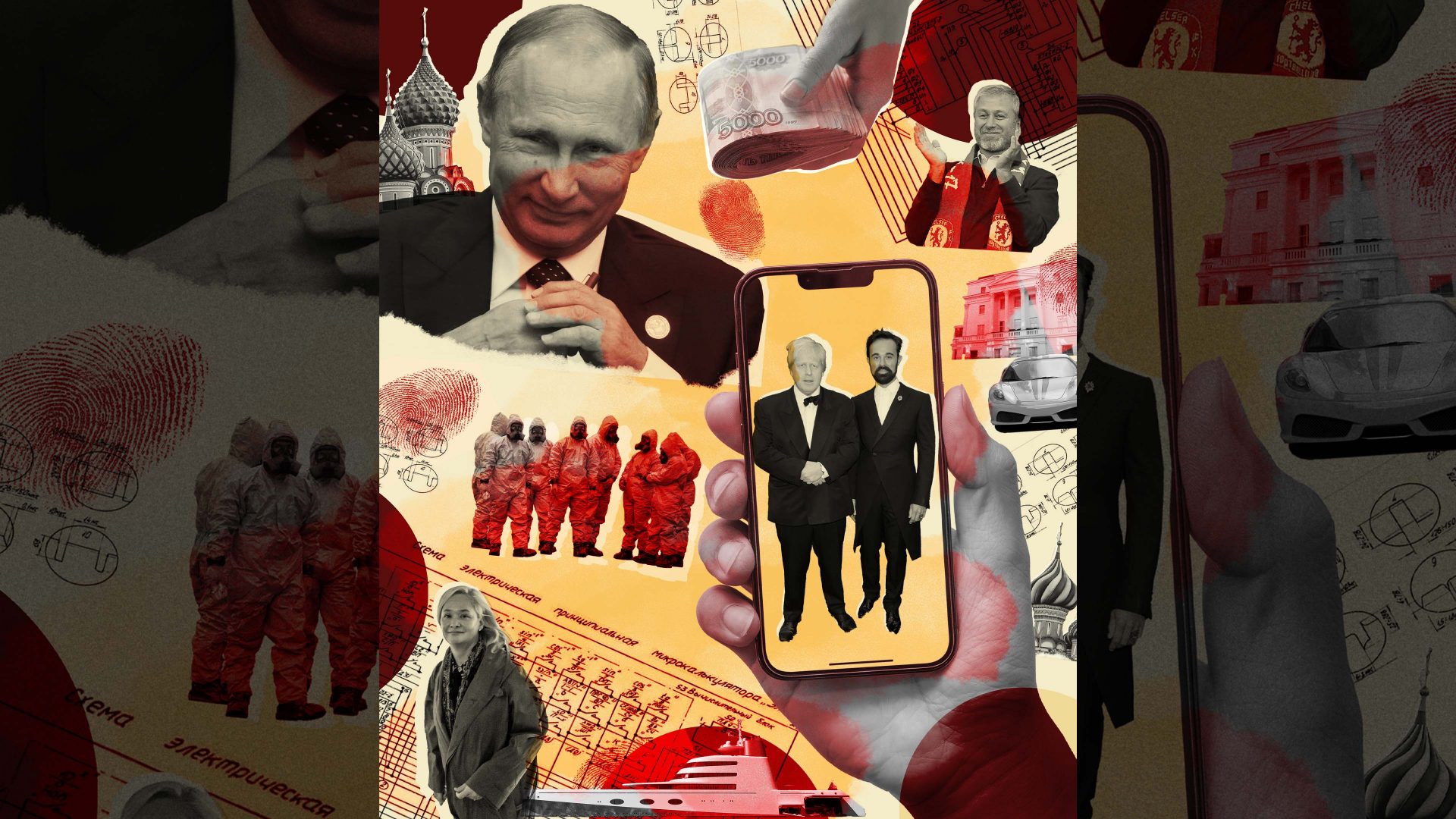

Like Le Carré, Charles Beaumont is a former MI6 officer turned writer, and also like his literary forebear he has produced a book on the secret contest between Britain and Russia – but the world he depicts in his debut, A Spy Alone, is very different to that of Le Carré and Philby.

Charles Beaumont is not his real name. A former intelligence officer who served in several war zones around the world, company rules dictate that he must use a pseudonym. When I spoke to him via Facetime, he appeared on my screen as an early middle-aged man wearing glasses. Judging from the background noise, he seemed to be in the waiting room of a railway station.

The cold war spies, like Philby, were essentially lone undercover investigators who infiltrated government departments or research bodies in order to steal information and channel it back to Moscow.

“What seems to be happening now is in a way much grander, much more ambitious,” said Beaumont. Russia’s aim is no longer simply to put agents into Britain’s institutions. Now, he says, they aim “to infiltrate our entire political system and to make it rotten from the inside.”

This plan has worked “to a very great degree”, says Beaumont, pointing out by way of example that “one of the largest donors to the Conservative Party was the wife of a former Russian minister.”

This is a reference to Lubov Chernukhin, who donated a total of £1.8m to the Conservative Party, which bought her a game of tennis with Boris Johnson and dinner with Theresa May. What else it might have bought her is not clear.

Her wealth comes from her husband, Vladimir, who is closely linked to the Kremlin. The origins of his fortune are uncertain.

“The Conservatives will defend that and say, ‘oh but they’re not Russians, they’re British citizens’,” says Beaumont. “Well, of course they are, because they’ve bought British passports.”

In Beaumont’s novel, Russian agents recruit a spy ring that succeeds in corrupting the highest levels of the British state. A group of unelected political advisers, seedy passport salesmen and business fixers have turned Britain into a hard right, populist husk for their own financial gain, all of it driven on by dirty Russian money. It’s a thriller, sure, but the corruption it depicts is unsettlingly believable – how close does it come to the truth?

A bit of scepticism is healthy when dealing with subjects like this. Spies and novelists – and, yes, even journalists – can often go down the conspiratorial rabbit hole. But there have been some cursory inquiries into Russian meddling in British public life, and they seem to fit with Beaumont’s assessment.

In its 2020 report, for example, the Parliamentary Intelligence and Security Committee concluded that: “The UK is clearly a target for Russia’s disinformation campaigns and political influence operations and must therefore equip itself to counter such efforts.”

When I put this to Jonathan Evans, the former director general of MI5, he said: “Given that the Russians have a long history of interfering in the political life of countries they see as targets, then it is almost unthinkable that they would not have tried to use money to this end.”

After his time at MI5, Evans went on to chair the Committee on Standards in Public Life, which conducted research into the regulation of election finance. “We identified a number of fairly basic vulnerabilities in the UK regulatory framework,” said Evans, “including vulnerabilities to foreign money entering the system.” Which tells us that, though Beaumont’s novel may be fiction, it is not fantasy. And yet the issue of Russian money and influence in British public life remains a highly sensitive issue – and an embarrassing one.

No one likes admitting they’ve been deceived, particularly politicians. And even when they know they’ve been duped, it’s hard to get people to do anything about it. Just look at Brexit.

The Russian dirty money problem is not just psychologically awkward, it’s also a matter of broad political shame that crosses party lines. In the early 2000s, Russian oligarchs, particularly the multibillionaire energy company owner Oleg Deripaska, got close to members of the New Labour government.

Russian money has also been influential within the Conservative Party and across the hard right, particularly during the Brexit referendum, when inexplicably large sums of money began flooding into the Leave campaign. Despite denials from Leave campaigners, there is strong cause to believe that some of that money was Russian in origin.

The growth of the Russian presence in British public life was at first gradual, and then very sudden. A new, wealthy kind of post-Soviet Russian started showing up in London during the late 1990s. People had made fortunes during the financial bedlam that followed the collapse of the USSR, and they wanted somewhere to spend it.

These high-rolling visitors poured money into the capital’s property market, the coffers of the private schools and the pockets of the Mayfair fund managers. By the early 2000s, there were so many Russians in London that they were beginning to attract attention, particularly when Roman Abramovich bought Chelsea football club, in 2003.

“At a certain point,” says Beaumont, “Russia became a cool brand in London. It was not to everyone’s taste. It was high-end, Mayfair, nightclubs, beautiful women, expensive cars – all that sort of glamour was almost completely identifiable with Russia. Which is ironic, because when I was a kid in the 80s, Russia was this dowdy place where everything was brown.

“Perhaps you could say it reached its apogee when Russia hosted the Winter Olympics (2014) and the World Cup (2018). Everyone knew they had bribed their way in,” Beaumont continued. “And yet somehow it didn’t matter, because we had decided it was fine as long as they were buying our properties and sending their kids to our private schools.”

But alongside the sporting pageants, a much darker Russia was emerging. In 2006, Alexander Litvinenko, the former FSB operative, was murdered by Kremlin hitmen in London using polonium, a radioactive poison. Vladimir Putin invaded Georgia in 2008, and annexed Crimea in 2014. In 2018, Russian operatives used a nerve agent in Salisbury in an attempt to assassinate a former Russian double agent, Sergei Skripal, accidentally killing a local woman, Dawn Sturgess.

Yet none of this was enough to make certain British politicians re-examine their relations with wealthy Russians. On the contrary – on his way back from the Nato summit where western leaders had discussed their response to the Salisbury attack, the British foreign secretary, Boris Johnson, attended a party at the Italian mansion of Evgeny Lebedev. He is the son of Alexander Lebedev, the billionaire oligarch and former KGB spy.

Johnson was not accompanied by either security or ministerial officials at the party and there is no account of his discussions with his Russian billionaire host. In 2020, Johnson gave Lebedev, now the owner of the Evening Standard and the Independent, a life peerage.

The journalist and historian Max Hastings is a long-time observer of British public life. “I’ve felt for 30 years that it was madness to allow large numbers of Russians to bring into Britain what is essentially a gangster culture,” Hastings told me, via email. “But while New Labour were eager to open their arms to rich Russians, the Tories have been worse.”

The former Conservative home secretary Douglas Hurd, Hastings recalled, once told him with a chuckle: “It’s always been the same. Pirates come to Britain, buy some respectability, then they send their sons to Eton and it’s all all right.”

Hurd’s assumption that, in time, Russians living in the UK would become more British in their values seems to have been entirely wrong – if anything, the opposite is true. We have become more like them.

According to Beaumont, there now exists “a class of British professionals who are on the Russian dime. They might be lawyers, bankers, PR professionals, private investigators, but in one way or another all of them are paid for by the kleptocratic elite that runs Russia.”

But although London welcomed in a wave of Russian money that has worked its way into the most sensitive parts of British public life, the effect of that money is hard to gauge. As Tom Keatinge, the financial crime and security expert at the Royal United Services Institute, put it: “Russian money has clearly succeeded in ‘buying’ access – so-called ‘access capital’. Whether that access has resulted in demonstrable political influence remains speculation.”

An indication of why it is so hard to assess the effects of Russian money came in the Intelligence Committee’s 2020 report, which concluded, remarkably, that Britain’s spy agencies “do not view themselves as holding primary responsibility for the active defence of the UK’s democratic processes from hostile foreign interference”.

The report continued: “During the course of our Inquiry [the intelligence agencies] appeared determined to distance themselves from any suggestion that they might have a prominent role in relation to the democratic process itself.

“Overall, the issue of defending the UK’s democratic processes and discourse has appeared to be something of a ‘hot potato’.”

A paragraph or so later, the report recounts what happened when the committee asked to see all available secret intelligence on pro-Brexit and anti-EU trolling activity during the 2016 EU referendum.

“In response to our request for written evidence at the outset of the Inquiry,” the report reads, “MI5 initially provided just six lines of text.”

Beaumont says: “On the question of Brexit, no one has done a thorough investigation. No one has, for example, got to the bottom of who funded a huge wrap-around newspaper ad that was put around the outside of the Evening Standard, which I think was the single biggest media buy during that campaign.

“What of course we do know, and I heard this from intelligence people at the time, including across Europe,” says Beaumont, “was that the Kremlin was absolutely delighted at the outcome of Brexit.”

While the British spy agencies may have shied away from looking into election meddling, the US authorities were much more assertive. The Mueller Report into the 2016 presidential election, overseen by Robert Mueller, former head of the FBI, found that Russia had interfered “in sweeping and systematic fashion” in America’s democratic process, through the spread of disinformation and the use of hacking operations against the Democratic Party.

But then, as Greg Treverton, the former chairman of the US National Intelligence Council, pointed out, Russia’s meddling in the 2016 US election on behalf of Donald Trump was so extensive and so brazen that it was hardly covert at all.

“In some ways, in 2016, it was almost as though they wanted us to know what they were doing – ‘we can do this to you’,” he said. “It certainly had an effect.”

As for Trump’s chances of re-election, Treverton said, “Ian Bremmer [the political scientist and historian], who I trust, says it’s six out of 10 that he’ll win. I wouldn’t put it quite that high. But he could easily win, that’s for sure.”

A Trump victory would have deep consequences for European security, and for Europe’s ability to confront Russia. Trump’s well-known animosity towards Nato could result in the US in effect leaving the organisation, either by withdrawing financial support, or by declining to assist a fellow member state under attack.

The US approach to the Ukraine war would change in an instant – Trump would push Kyiv into negotiations with Putin, an outcome that would delight the Russian president. More broadly, Trump’s political instincts would move US diplomacy in an entirely different direction. He has zero affinity for European liberals such as Emmanuel Macron, Olaf Scholz, or Keir Starmer. His taste is for “strong men” leaders, like Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Viktor Orbán – and Putin.

The journalist John Sweeney, who appears regularly in these pages, framed the current situation in his typically direct way. “We are at war with Russia,” he said. “It’s just we don’t know it. The problem with this war is it’s not a war we are fighting with things that go bang. We are fighting with disinformation, with corruption, with poisoning of the British political system. But it is serious and we need to address it.”

Not everyone sees it quite so starkly. Richard Dearlove, the former head of MI6, warned that assuming all Russian money in London was attached to Moscow was “a very simplistic view”. Were there individuals based in London who were close to Putin with malign intentions? “Yes,” he said, “some”.

When pushed about large Russian donations to the Conservative Party, and whether that money was Kremlin-approved, Dearlove said: “Some of it might have been – but the idea that there was an organised subversion of British politics, I don’t really buy that.”

Even if Dearlove is correct – and of all the experts I spoke to for this article, his was the minority view – we still have to accept that we don’t know what effect decades of dirty Russian money has had on Britain.

It’s not a comforting thought, especially now, as we enter a period of extreme international instability that hinges largely on the outcome of the US election, a vote that Russia will attempt to influence. Britain will also hold an election in the coming months – the recent online “spear-phishing” attack against Will Wragg, a Conservative MP, indicates that malicious actors may already be circling.

And yet the UK still has no clear picture of how susceptible its political system is to external influence from Russia and other adversaries, and no idea of how any weaknesses have been exploited in the past.

The next government must make up for this failure. “What PM Starmer needs to do is appoint an inquiry into Russian influence in British public life – not just politics,” said Beaumont. “It needs to have the same powers that the Iraq Inquiry had so it can go to any classified or otherwise sensitive material.”

It would be a highly controversial decision, one that goes against the strong human instinct to suppress moments of embarrassment and failure. But an inquiry would begin to give us the full story. At some point, Britain needs to hear it.