In the video an elderly American veteran, Lehmann Riggs, was returning to Germany for the first time since the end of the second world war. He relived the moment when his comrade Raymond J Bowman was shot dead, just two feet away from him. Here, in this house.

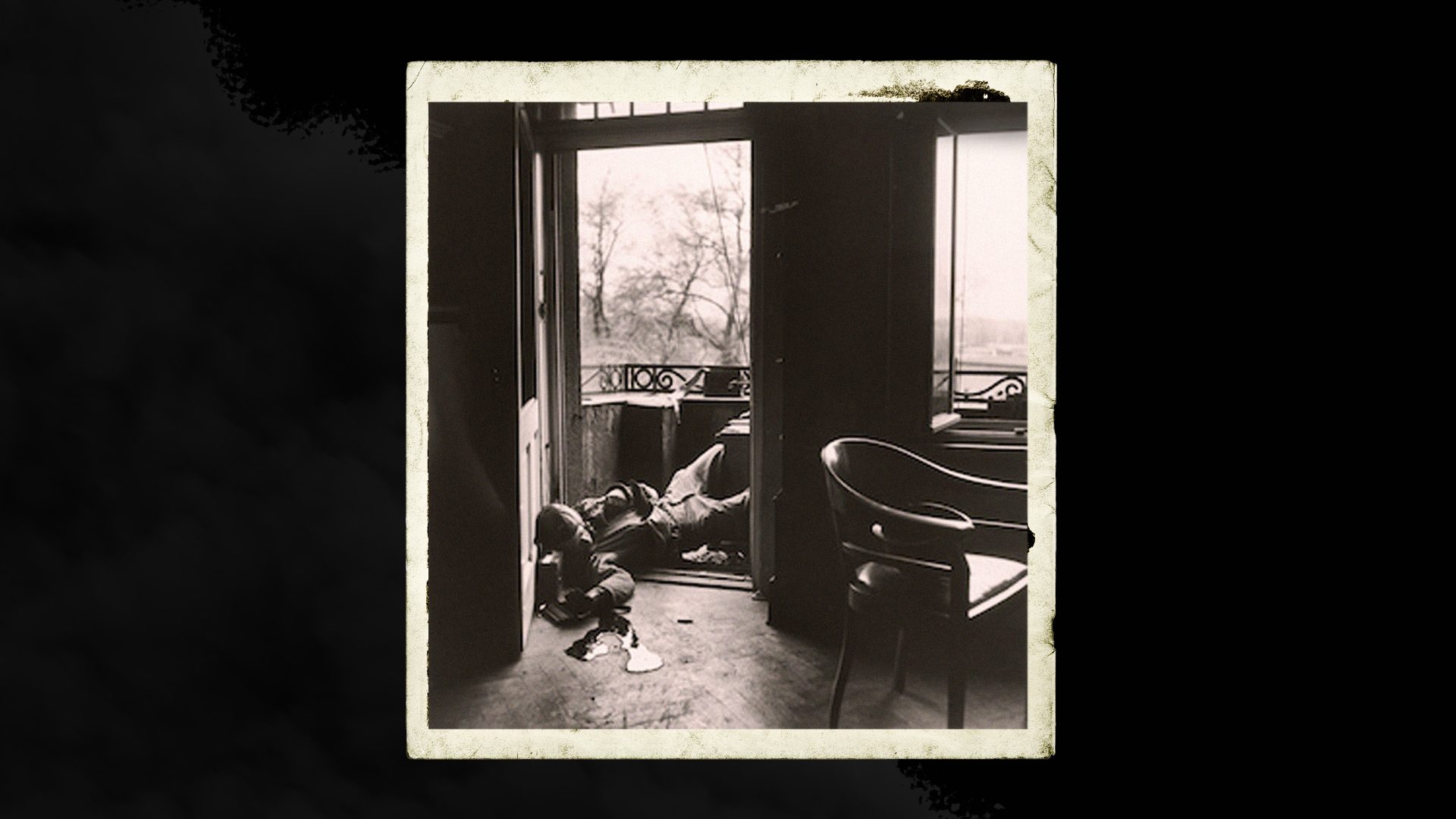

Lehmann is weeping, and as I watched the film, so did I. The footage shows him moving around the upstairs room and the balcony where he and Private Bowman were manning a machine gun, half-hidden behind the balustrade.

“I saw him fall, right here,” says the old man. “I knew he was gone, right away. There was nothing I could do. I stepped up to the gun and took over.”

It was April 18, 1945. But they were not alone in the bedroom of the old house overlooking the Zeppelin Bridge in Leipzig. The war photographer Robert Capa was also there. His camera captured the last snapshot of Private Bowman alive, reloading the machine gun, and then the moment of his death.

Capa sold the pictures to Life magazine, where they were published under the banner deadline: “The last man to die”.

No one knows for sure if he really was the last allied serving soldier to die. The war in Germany officially ended on May 8. But we can be sure he was the last one to die on camera.

Bowman had celebrated his 21st birthday only two weeks earlier. He had taken part in the Normandy landings on D-day, been wounded in action and achieved the rank of Private First Class, as well as the Army Good Conduct Medal and a Purple Heart.

Bowman’s remains were flown to his home town of Rochester in New York State, where they were interred in the Holy Sepulchre Veterans’ cemetery.

The street where he died has been re-named Bowmanstrasse. And the house where he and Lehmann Riggs had their machine-gun position is now a memorial. It’s all thanks to a citizens’ fundraising initiative (Bürgerinitiative) supported by – of all people – the famous local comedian Meigl Hoffmann. Funds were raised to restore the “Capa House” at No 61, Jahnallee, without modernising it too much, so that it still has the authentic look and feel of the 1940s.

Enough money was raised for an exhibition entitled War is Over, and some of the funds were used to bring Lehmann Riggs back to Leipzig from the US for the official opening ceremony.

Now the Capa House has developed into a full-scale museum. It does not only honour Raymond J Bowman but also Robert Capa, the American-Hungarian Jewish journalist who teamed up with German photographer Gerda Taro, also Jewish, to change the face of war photography.

They were colleagues and lovers. Together they travelled to Spain during the civil war, always on the side of the anti-fascists. They documented the massacre at Málaga, the hunger and desperation of displaced persons, the brutality of Franco’s shock troops. These photos are now on display in the Capa House in Leipzig.

But Taro did not live to see the second world war. She was crushed by a tank while photographing clashes at El Escorial in Spain in 1937. In Leipzig, they remember her name on Tarostrasse, near the university halls of residence, and in the Gerda Taro Gymnasium (high school).

Capa was also killed in action, but much later. He trod on a landmine while photographing French troop movements in Vietnam in 1954.

This year they are marking the 80th anniversary of the end of the second world war across Germany and here, in the former Russian occupation zone, the slogan most frequently used is not, as we usually say in Britain, “Lest we forget”. It’s much more urgent, rooted in the present political polarisation, antisemitism and tensions: Nie wieder fascismus. Nie wieder. “Never again for fascism. Never again.”

Jane Whyatt has worked as a journalist, newsreader and independent producer for TV networks