Fanø, a tiny island off Denmark’s west coast, remains proud of its seafaring past. Superbly crafted models of wooden ships hang from the rafters of the island’s two parish churches.

Today, tourism rather than shipbuilding keeps the island’s economy afloat. In summer, the population of around 3,000 swells by thousands more, the majority of them from Germany. Hamburg is only a little over 300km away and Germany has relatively little coastline – Denmark has plenty of beach to share.

In the tourist season, churches double as concert venues, part of the Fanø Festival. Music from string quartets rises to the sails of the model ships. Swallows occasionally fly past the church windows, enjoying the last light evenings of the Scandinavian late summer.

That evening there was a reminder of something much more menacing, murderous even. Introducing the next piece of music, Roxanna Panufnik’s Hora Bessarabia, the double bass player, Kristina Edin, explained that it had been played at Auschwitz in 2017. The performance followed a request from a Holocaust survivor, Eva Mozes Kor, to hear music at the site of the death camp. The music that followed, played only by Edin and a violinist, Alexi Kenney, was especially memorable for its associations.

The introduction had been made in English, a language that most people could understand, though I think I may have been the only native speaker in the audience. Most of the concert goers that evening were elderly. Almost 80 years after the end of the second world war, it is unlikely that any of them remembered the conflict, but I was certainly sitting among descendants of Germans who had occupied other European lands, and Danes who had lived under occupation.

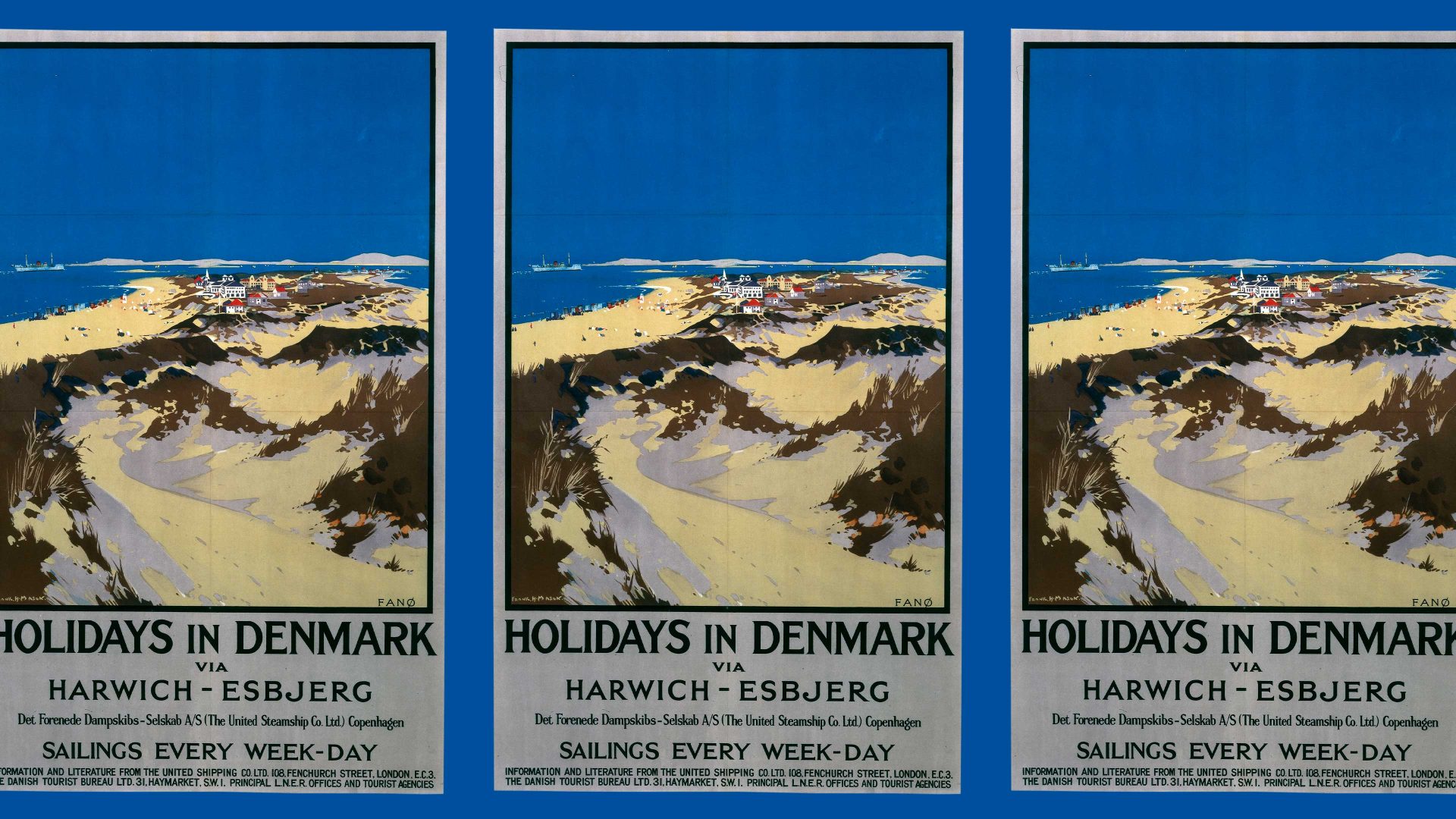

Signs of the war endure on Fanø. Grim concrete bunkers, so solidly built they are all but impossible to remove, still scar the dunes. Their dark grey concrete among green grass and white sand casts a shadow on even the brightest summer afternoon.

The island’s proximity to northern Germany meant it was seen as a potential target for an allied attack. Near Fanø’s northern tip, the remains of a gun emplacement guard the entrance to Esbjerg harbour on the mainland. In the war’s closing stages, Fanø became home to German refugees, running terrified from the westward advance of the Red Army.

The concert concluded with Richard Strauss’s Metamorphosen, the inclusion of his work a reminder of the complicated legacy of a composer who continued to work as normal in Nazi Germany, but also used his position to try to protect his Jewish daughter-in-law and her family. A denazification tribunal in postwar Germany cleared him.

The piece was performed by a string septet. The audience applauded joyously and appreciatively as it ended. The music played that evening was among Europe’s great gifts to world culture; the reference to the most murderous episode of the second world war a reminder of how Europe can fall.

Many of the vessels in the church rafters are warships, with cannons recreated in miniature to recall the battles Denmark has fought during its history to defend the coasts, the same beaches that it now promotes to tourists. And this summer the swallows shared the skies with the occasional warplane roaring high over the North Sea. In July, the United States secretary of state, Anthony Blinken, confirmed that the first US-built F-16 fighter jets pledged by Denmark and the Netherlands were on their way to Ukraine.

James Rodgers is a former BBC Moscow correspondent. He now teaches Journalism at City, University of London