That morning Paris was slowly waking up: shops still shuttered; some of the metal slats coloured with graffiti, which always seem to my eye to have superior artistic qualities to that seen in other capitals around the world.

Here and there lights shone through the gloom of a February morning – this was no springtime in Paris – as cafes opened for early trade. Schoolchildren were already hurrying to lessons. I was on my way to the Gare de l’Est to catch an early train.

Later that day, the French prime minister, François Bayrou, was due to face a no-confidence vote – the latest in what has been a turbulent recent few months in French politics. Bayrou survived, for now, at least, thanks to the Socialists and the far right National Rally deciding not to support the no-confidence motion.

One success in parliament is not a sign that stability is returning to French politics. There are presidential elections in April 2027, and the National Rally’s leader, Marine Le Pen, is consistently making the strongest showing in the polls.

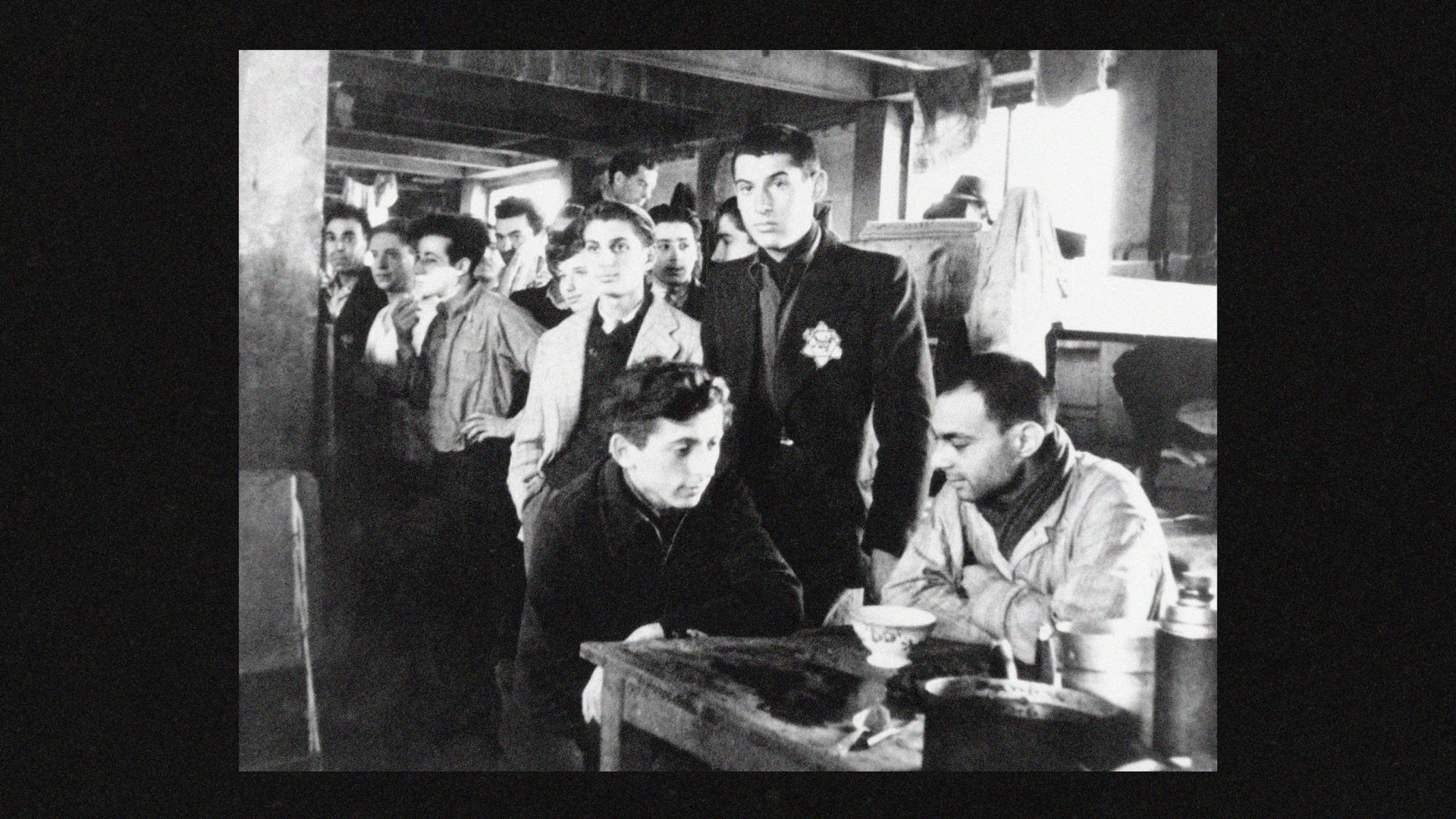

I was on my way from Paris to Mannheim in Germany. The train took me though territory that France and Germany fought over in 1870, and twice in the 20th century. There were reminders of these past wars at the station: plaques commemorating the tens of thousands of French Jews taken east to Nazi concentration camps between 1942 and 1944; memorials to railway workers killed fighting for France.

Fog covered the land most of the way. There was frost on the trees. I arrived in Mannheim to streets where the main flashes of colour, save for shop signs, were posters for the upcoming elections.

Although the part of Germany I was visiting is not a stronghold of the far right Alternative for Germany (AfD), during my visit I did not see even a single AfD poster among the many vying for voters’ attention. Instead, stickers on election posters for the conservative CDU criticised them for recent parliamentary motions on new immigration plans that drew AfD support. That was a shocking departure from a cross-party consensus that mainstream politicians should not work with the far right.

That is not to say there were not striking signs of Europe’s current troubled politics. The market square in Mannheim still has floral tributes to Rouven Laur, a 29-year-old police officer stabbed here last year by an Afghan asylum seeker who attacked an anti-Islam rally. Laur died days later of his wounds.

The far right are growing forces in both France and Germany. Extreme nationalism, especially as practised in German politics, was one of the poisons that cursed Europe in the last century.

The EU was of course designed in part to stop France and Germany – these two titans of European history – from going to war again. Both are going through uncertain times: we Europeans should not forget that our security has to a large extent been guaranteed by the United States in that time – but no longer, it seems.

The sun did not shine for the whole of my short trip. The gloom should not stand as a metaphor for the current state of affairs. This is not a bright time to live in Europe, but nor is it Europe’s darkest time.

The journey I made was through a country wrecked by war in living memory, and many times before. Europe’s politics may be alarming, but that does not mean history will inevitably repeat itself – especially if we remember that, not so long ago, those grey winter landscapes were once battlefields.

James Rodgers’ next book, The Return of Russia: From Yeltsin to Putin, the Story of a Vengeful Kremlin will be published later this year by Yale University Press