Just before he oozed into Downing Street in July 2019, Boris Johnson granted an interview to the Daily Mail, designed to establish his strength and resolve. In it, he was asked to name his favourite movie moment and he duly chose the “multiple retribution scene in The Godfather,” the sequence when Michael Corleone, newly anointed as a mafia Don, has his many enemies wiped out while he attends a baptism.

A week or so later, when he finally entered No 10, Johnson did some wiping out of his own, purging the cabinet of Remainers. Taking their cue from his earlier comments, the gentlemen of the press duly made breathless comparisons between him and Michael Corleone (never mind that Don Michael was disciplined and iron-willed.)

The prime minister (at the time of writing) is far from the only person to admire the film. Colonel Gaddafi was a fan, as was Saddam Hussein. Barack Obama loves the saga too (Part II is his favourite film). But you don’t need to be a world leader to dig The Godfather series; they’re among the most popular and enduring films there are.

So popular, in fact, that you don’t need to have seen them to have felt their impact. In the same way that you’ll have heard about half the script of Hamlet before you ever actually see the play, anyone watching The Godfather and its sequels for the first time will find much is familiar, with their unrefusable offers, horses’ heads and ice-cold dishes of delicious revenge. More than Casablanca, Star Wars and The Wizard of Oz (probably combined), the three Godfathers have permeated the cultural bloodstream, a collective touchstone offering wisdom for business, for families and even gastronomy.

It is in politics, however, where its influence has been most keenly felt. One of the reasons the film’s dialogue feels so ubiquitous is because of the frequency with which it is invoked in news coverage: rare indeed is a reshuffle that isn’t framed with “keep your friends close, but your enemies closer,” (to quote Michael in Part II) or of intra-party discord settled by “an offer he couldn’t refuse” (as Michael said of his father Don Vito’s negotiation strategy in the original).

But if political reporters are enthusiasts, then politicians – without hyperbole – are obsessives. David Cameron apparently watched them “again and again and again”, and Ken Livingstone is a fan too: “I have often thought that… The Godfather is a much more honest account of how politicians operate than any of the self-justifying rubbish spewed out in political biographies and repeated in academic textbooks,” said the celebrated newt-fancier. He’s especially fond of the line, “Tell Mike it was only business. I always liked him,” as spoken by a would-be traitor. For him it “typifies the way most politicians deal with each other”.

Then there’s Dominic Cummings, a more obvious student of the Corleone clan. When he accompanied his then-boss into office, he was often dubbed Johnson’s consiglieri, referring to the lawyer/chief of staff/wise counsel to the Don (in the first two films, it’s the character played by Robert Duvall, Tom Hagen). Of course, since then there’s been a plot twist that no one saw coming and the consiglieri has turned on il padrino. As he pursues his vendetta, you might remember that Mr C has been known to quote Don Michael’s words from Part III: “Never hate your enemies. It affects your judgement.”

It’s even said that some MPs show the films to new staffers to give them a flavour of the job. For example, the very first scene, in which Don Vito agrees to help a lowly undertaker secure justice, is a practical illustration of the wisdom of granting favours and pocketing the gratitude for when you need it (“Some day, and that day may never come, I will call upon you to do a service for me”). Useful either if you want someone to patch up your murdered son so he can have an open-casket funeral (Don Vito) or if you need someone to parrot a line on Twitter (politicians).

It’s not hard to understand why politicians are so hypnotised by these films. Although notionally about a crime family, they’re mostly about power, the rawest stuff in politics. They show how power is gained, wielded, guarded and dispensed, and that can only be appealing to those who’d like a bit of power themselves.

Few people, after all, enter politics to loll on the backbenches and wait for a pension. But politics is full of pitfalls. Why wouldn’t you quote the aphorisms of someone who seems to navigate his own trade so well? The films show that the application of power is an art, of knowing when to let rip (cf Johnson getting rid of half the Cabinet) and when to hold back (“I don’t like violence, Tom. I’m a businessman; blood is a big expense”– Sollozzo). We could say that Don Corleone is the most important Italian political theorist since Machiavelli.

Above all, the films show how seductive power is. Michael may be a loathsome man, up to his neck in all sorts of things that don’t normally draw admiration, but his reptilian intelligence and fearsome will make him undeniably compelling. He’s up there with Richard III (the Shakespeare character rather than the Leicester car-park one) in the anti-hero stakes, characters who we can enjoy for their ruthlessness and implacability (“If history has taught us anything, it is that you can kill anyone,” – Michael, Part II). This is catnip for the sort of person who likes the thought of themselves being in charge: in the world of the Corleones, power automatically seems to make someone more intriguing, whatever their character flaws.

Of course, there is often an unflattering disconnect between the charismatic actors (and the oversized characters they play), and the minnows of Westminster. It was bad enough watching Big Dog make like he was Marlon Brando when he cleared out the Cabinet, but an even more bathetic evocation was made before the election of 2015. Back then, there was concern in England that Ed Miliband’s Labour might do a deal with the SNP (you will remember the poster of Red Ed in Alex Salmond’s pocket).

Miliband was advised to shut down the conversation, and, again, The Godfather was cited: in Part II, Don Michael dealt with an interlocutor by saying, “My final offer is this: nothing.” Don Ed, it was suggested, ought to say the same to Donna Nicola Sturgeon. The trouble is, advocates of this strategy didn’t think how utterly risible it sounded: bless him, but there are few people in British politics who seem less suited playing the role of the Mephistophelian Michael than Ed Miliband. (When he became Labour leader, one of its then MPs, Tom Harris, even wailed that “we’ve elected Fredo!” in reference to Michael’s ineffectual brother, runt of the Corleone litter).

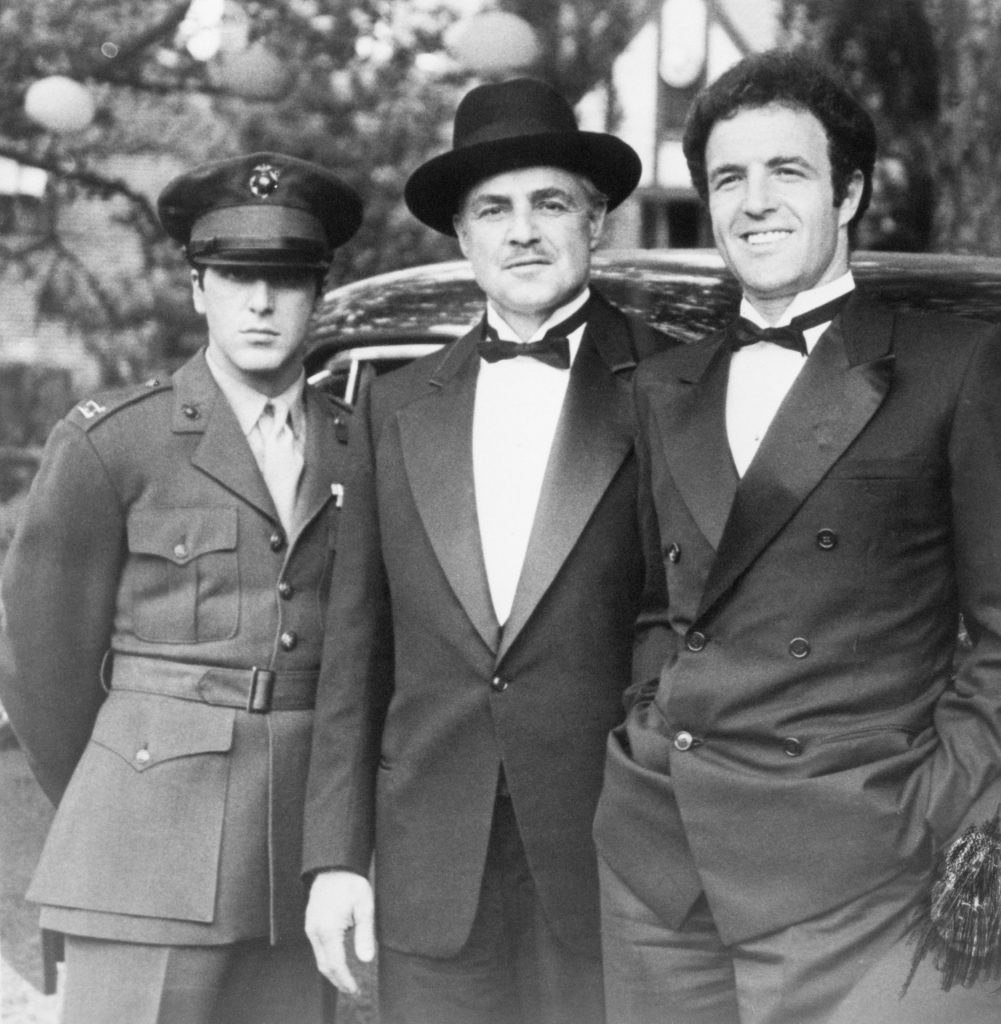

The most egregious example of how these films have caught the imaginations of an entire political class is The Godfather Doctrine, a book by American scholars Wess Mitchell and John Hulsman, published in 2010. It uses the films to allegorise the potential choices for how American foreign policy might develop in the Obama era, moving from the old, dominant, ways represented by Don Vito, looking for a path between the bullish approach favoured by the more hawkish, rightwing sort of adviser, as epitomised by Vito’s eldest and most intemperate son, Sonny (the character played by James Caan), and the consensual don’t-rock-the-boat methods recommended by consiglieri Tom Hagen, which liberals might prefer. Instead it suggests that the realism of Michael is the ideal approach, keeping the peace but knowing when to brutally massacre your enemies.

Barack Obama himself cited The Godfather Part II as his favourite movie, even if he was one of the few politicians who never seemed to use it as a handbook. In fact, it’s one of the few things he shares with his opponents/enemies. Former New York mayor turned ludicrous celebrity lawyer Rudy Giuliani is a fan, as is Ted Cruz, weirdo far-right junior senator for Texas: in fact, he’s one of the few people who even loves the third one. It will not come as a surprise to know that Giuliani’s present employer, Donald Trump, is a fan too, or at least claimed to be in his pre-politics days.

It’s commonplace to talk about Trump being the point where distinctions between politics and entertainment blur, and the same is true of politics and comparisons to The Godfather. The connections go deep: Francis Ford Coppola, the co-writer and director of the saga, revealed that he overlapped with the boy Trump at the military academy they both attended in New York; Coppola was four years older when young Donald was enrolled and so interaction was limited (the director remembers “a rich kid”) but their paths would occasionally cross over the years.

One of those occasions was the filming of The Godfather Part III; the sequences set in the Atlantic City casino were filmed in properties then owned by Trump. (We must be grateful the future president didn’t inveigle a walk-on for himself.)

He might also have offered his services as accuracy adviser, for Don Donald has had connections with the real Cosa Nostra since his days as a property developer. They’re “very nice people”, he says.

Those mafia connections often provided a frame of reference for the Trump White House, for the press, fellow politicians and even for law enforcement (cf James Comey, former director of the FBI, who compared Trump to a mob boss “because I’ve known mob bosses and helped put them in jail”). More surprisingly, members of the Trump clan were happy to invoke comparison with the Corleone family.

No one could fault the taste of anyone who channels the films. They represent one of the very zeniths of cinema and remain utterly compelling. That said, there comes a point when we might wonder if it’s not a great thing that they seem to have such a hold on our political classes.

Certainly, Francis Ford Coppola is unhappy about it. Commenting on Johnson’s unwanted endorsement, he said in 2019, “I feel badly that scenes in a gangster film might inspire any activity in the real world or [provide] encouragement to someone I see is about to bring the beloved United Kingdom to ruin.”

The Corleone family are vicious criminals, grasping for profit at any price. If the films are concerned with power, they’re also concerned with the moral rot it can bring. Those who would see a role model in Michael Corleone have rather missed the point: power hollows him out and leaves him dead behind the eyes. Beware those who take a cautionary tale as an instruction manual.

The Godfather is re-released on February 25