What has been dubbed “Awful April” – because of a combination of council tax hikes, increased energy bills and other cost of living miseries – has one ray of sunshine for low-wage workers. The minimum wage for all ages is increasing well beyond inflation.

What is the national minimum wage for 2025?

A full-time minimum wage worker will now earn just under £26,000 a year, and while the minimum wage for under-21s is still lower than this level, it has increased by much more, reducing the differential between the two groups.

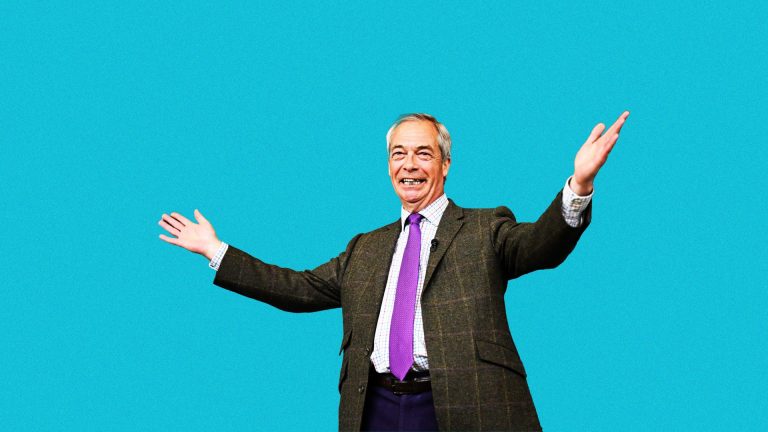

Though Labour has increased the minimum wage by more than the Conservatives, as a policy it has enjoyed strong cross-party support, despite being hugely contentious when it was first introduced.

When the last Labour government introduced a national minimum wage in 1999, it was accompanied by dire warnings that it would lead to huge rises in unemployment – which has never proven to be the case. Since then, Conservatives have made no effort to abolish it, and instead tried rebranding it as a “living wage” – and generally allowed it to rise by at least the level of inflation.

Part of this is because, as policies go, it is extremely handy for government. A minimum wage increase lets the government take credit for making millions of people better off, while having someone else – private sector employers – pay much of the money (though the state directly and indirectly employs plenty of minimum wage workers, too).

More than 25 years since its introduction, though, the policy has had significant effects on the nature of work in the UK, which are barely even known about, let alone discussed – and one of the biggest effects is that if you leave the very top 1% or so of earners aside, wage inequality in the UK has been falling for decades.

This chart shows how earnings have changed at different levels since 1997. The thick black line represents the median earner – the person right in the middle, where half of workers earn less, and half earn more. The wages of the median worker have more than doubled since 1997.

But the wages of lower earners have gone up faster: someone in the bottom 10% of earners has seen their wages increase by about 2.5 times over the same period, and someone in the bottom 25% of earners has also seen their wages increase faster than higher earners. By contrast, the top 10% and top 25% of earners have only seen their wages increase roughly in line with the median worker.

In other words, except at the extremes of the 1%, wage inequality among workers has decreased markedly over the last few decades. The gap between high incomes and low incomes has been shrinking, not growing. But for many of us, that doesn’t chime with how the economy feels at the moment, at all.

Part of this is that wages are only one part of the picture as to how well off we are. The costs of everyday living are a major factor in how far those wages go, as are the availability of in-work benefits like tax credits. But perhaps even more than that is whether our wages let us accumulate wealth and security – such as by owning a home.

Wages may be showing signs of improvement, but on its own that won’t solve the problem

If you, or your parents, owned a home in the South East in the 1990s, you likely have significant family wealth now. If you didn’t, owning a home is a distant (if not impossible) prospect to even quite high earners.

The steadily increasing minimum wage does have some knock-on societal effects, though – not least a phenomenon known as “wage compression”, in which some “skilled” jobs requiring training or even university degrees don’t keep pace with the steadily increasing minimum wage.

This is most obvious in jobs which require degrees but which don’t traditionally pay well. London Centric editor Jim Waterson noted on Bluesky this week that local newspapers are still advertising jobs for fully trained journalists, requiring their own car, for less than the full-time minimum wage in the UK.

Because the UK’s productivity hasn’t increased in decades, and our economic growth is sluggish at best and often just simply non-existent, the pay premium for degrees or for work requiring a lot of training is shrinking – if once it paid 30% more per hour than minimum wage, now it’s 20%, 10% or even nothing.

Inevitably, that leads some people to wonder whether it’s worth investing the time, money and effort into getting those traditionally more desirable jobs. This reticence contributes to the UK’s skill shortages, which deepens the productivity crisis.

None of this makes increasing the minimum wage a bad idea in theory or in practice. Making work pay has always been fundamental to the Labour movement, and it is an effective intervention to try to eliminate in-work poverty.

But its shortcomings are a reminder that no single intervention is a silver bullet. For all that we focus on inequality, a more equal distribution of wages has done little to stymie the rise of populism in the UK, nor has it made us much happier or more cohesive.

Instead, it helps make the case for “abundance economics” – the idea that we should focus on what is scarce (and thus expensive) in our societies, be that energy, housing, or something else, and try to make it abundant. Without economic growth, the benefits of a rising minimum wage are muted, and its side effects are magnified. Without building enough housing so as to make it genuinely affordable to average workers, wages don’t turn into wealth or security.

The US is a far less equal society even than the UK, but the median full-time worker there earns £10,000 more than their UK counterpart (about £45,000 a year versus £35,000). Around ten states have a minimum wage comparable to the UK’s, with only two having it set at a higher rate than ours – but most American workers are still earning considerably more than their UK counterparts.

The minimum wage has been a success, perhaps even one of the biggest legacies of the Blair/Brown era – but it can only go so far in tackling what ails our society. Ultimately, it’s not enough just to keep on lifting the lowest rung. We need to raise the middle, too.