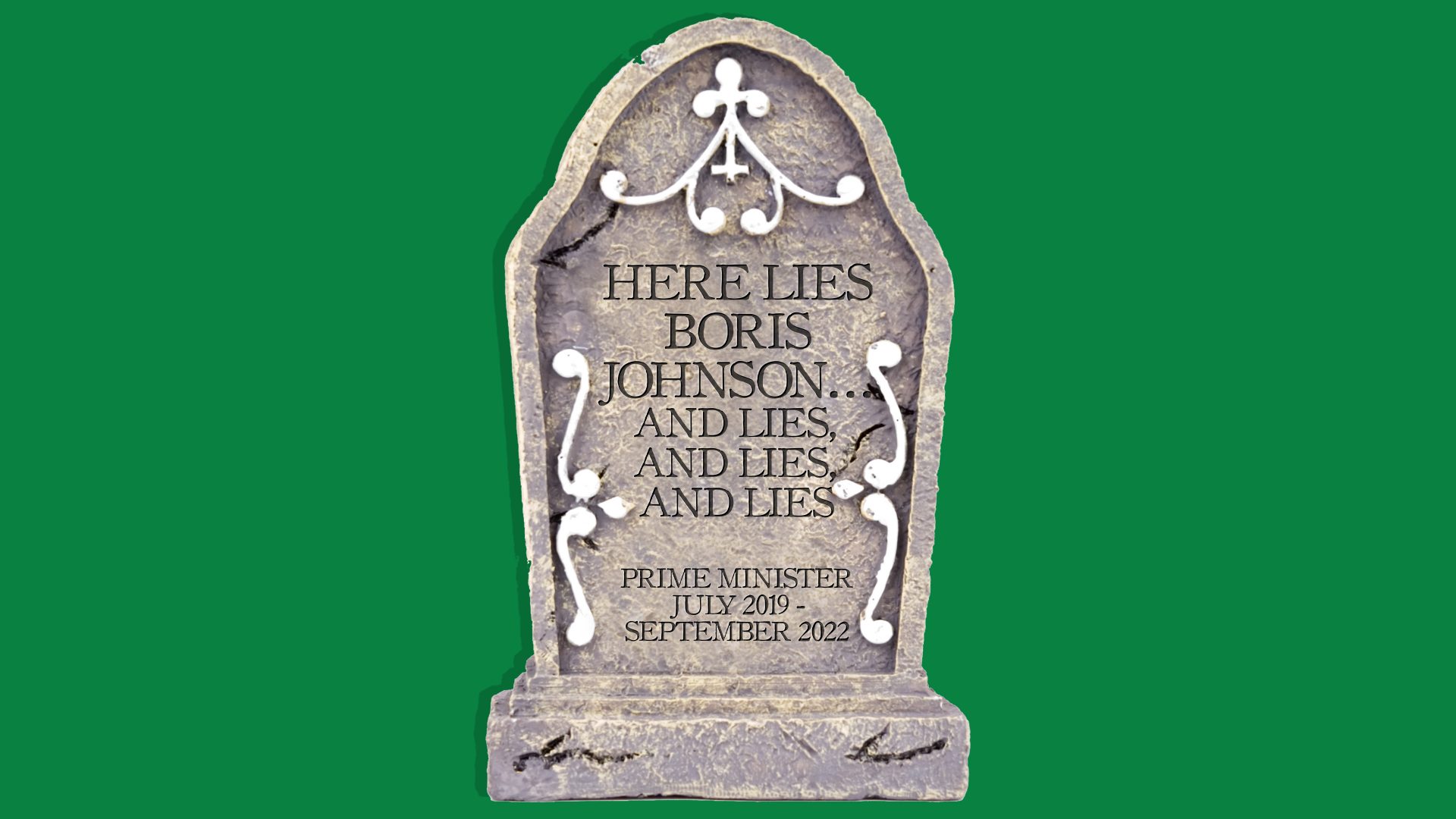

At least Boris Johnson is consistent. In the last days of his premiership, he is living down to the public’s expectations.

Having asked to stay on for the duration of the Conservative leadership contest out of a sense of duty, he spent most of August on holiday. When not vacationing, he decided to run the country from Chequers. The lost opportunity to tackle the energy crisis is felt by us all.

Now there is time for one last Johnson scandal: his rumoured plans for his resignation honours list. A man who in just two years has already created 86 new life peers plans to pack the Lords with dozens more.

His No 10 communications director Guto Harri – who oversaw the shambles that led to his ousting – a knighthood for a dismal six months in post. Conservative donors and loyalist ministers will be rewarded, with the culture secretary, Nadine Dorries, and Daily Mail supremo Paul Dacre rumoured for elevation.

A disgraced prime minister being able to pack one of parliament’s two chambers with dozens more cronies is rightly drawing widespread outrage. But the real question is whether we have a Boris Johnson problem, or a House of Lords problem.

Conservatives would like to suggest it’s the former – partly because they’re generally fans of tradition, but more because the party enjoys a significant inbuilt advantage in the Lords. Others call for the second chamber to be abolished entirely, and the Commons given full authority to draft and scrutinise laws. Which argument has the most merit – and if the Lords shouldn’t continue in its current form, what’s best to replace it?

The case for the status quo

The second chamber was originally made up of the Lords Spiritual – bishops of the Church of England, who still hold 25 seats – and the Lords Temporal, hereditary landed nobles who due to their stewardship of the land claimed a longer view of events than their colleagues in the Commons.

This hereditary principle was much derided even in the 19th century, but the Lords stubbornly resisted reform. It was only in 1958, when it was clear that Labour, with virtually no hereditary peers on its side, should not have any parliamentary agenda it possessed reversed by an unelected second house, that life peers could be created.

It was left to the prime minister to determine who should be so ennobled and no restrictions were placed on the number of peers, their party, or other use of these powers – peers trusted the PM’s judgment and propriety.

The house remained mostly hereditary peers until most were finally kicked out in New Labour’s first term. While it has led to the elevation of some experts, civil servants, lawyers and similar, it has also become a handy retirement home for political allies, and with close to 800 Lords, larger than the Commons.

No one wanted a House of Lords that looks like this – a ragtag mix of hereditary peers, bishops, political cronies, judges, and the odd expert or personality who has slipped through the net.

Why not just scrap it?

Almost every democratic system with a parliament has two chambers – usually with one being more important than the other. If we just scrapped the Lords and didn’t replace it with something, any PM with a decent majority could pass anything they wanted, unchecked. That would apply to prime ministers like Liz Truss, entering with no democratic mandate of their own, just as much as any other.

A second chamber acts as something to slow down dramatic changes, just as it acts as a mechanism to catch bad details in new laws – it is rare that the Lords stop a bill entirely, but they often get bad elements of it amended or improved.

While it initially sounds problematic, the whole point of a second chamber is to act as what’s called an “antimajoritarian measure” – something to make sure that just because one party has a majority at a given moment, it can’t automatically push through everything it wants extremely quickly, especially if it’s divisive.

This relies on a second chamber that has a different makeup from the first. If we need a second chamber, it can’t be a mirror of the Commons.

An appointed second chamber

Most recent proposals to reform the Lords have relied on creating a second chamber that is either 80% or 100% appointed. Such an idea feeds dated. If ever there was a time for a chamber of experts appointed by independent experts, post-Brexit Britain – when we’re divided on experts and disdainful of technocrats – now isn’t it. The broader problem with such a system is that someone would have to appoint the people on the appointments commission – and set the rules by which they are appointed.

With a government willing to pack the current Lords, BBC board and other public institutions, what would prevent them from doing the same with a process such as this? A second chamber with public legitimacy needs a direct public mandate.

Citizen assemblies

Utopian ideas for reform suggest we should step beyond traditional political systems. These include creating randomly assembled panels of citizens in different regions who deliberate on particular issues, with expert input, before reaching conclusions.

Other ideas include national consultation with some degree of policy input, or specially convened panels for particular legislation. Such ideas could be a valuable part of passing major legislation, but for the day-to-day of lawmaking are less than ideal.

When legislation needs to be passed with tight deadlines it can ping-pong between the Commons and the Lords multiple times in an evening, eventually passing only in the early hours when a final version is agreed. Thus, practically, assemblies seem impractical.

An elected second chamber

The option that seems attractive to most of us but which is unpopular with MPs is a second chamber whose legitimacy comes from the same source as that of the Commons – from the people. MPs fear an elected second chamber would threaten the primacy of the Commons, potentially rendering the country ungovernable.

Still, an effective second chamber would have to be done in such a way that it created a different composition and different personalities from the first. Ideas have included six-year terms, with a two-term limit, or even one term of 15 years. Barring members of the second chamber from being ministers also helps to create independence.

The big question then becomes what electoral system should be used to elect whatever comes after the Lords. There are issues with PR – the cronyism of list systems tends not to reward the most free-spirited candidates.

An alternative is for a second chamber based on regions and nations, partially compensating for the south-east’s huge population. This would give northern England and the nations outside England a bigger say in the national debate.

One big thing is clear: reforming the Lords won’t be easy. If the opposition is serious about actually changing it this time, they need a clear and thought-through plan answering these questions in their next manifestos. Otherwise, Boris Johnson, from beyond the political grave, will continue to win.