In the Liz Truss era, we are rapidly learning that after the storm you soon get… another storm. And before that has even started blowing over, another one. It is all storm, all the time.

The problems caused by the emergency budget already feel a lifetime away – but in reality we have yet to even start feeling some of the worst unintended consequences of the damage it did to the UK economy.

Most of us only have at best a vague sense of what gilts – a term for British government debt – are, or how market confidence in the government affects the FTSE or our chances of getting a job. But where many families will directly feel the consequences of the government’s economic mismanagement is the mortgage market – and that doesn’t look good for anyone. Startlingly, even those without a mortgage themselves may find themselves negatively impacted by what has happened.

If this were a L’Oréal advert, we would now do the science part – too often, explanations of what’s going on assume every newspaper reader understands the economics at work. But that leaves the rest of us having to try to puzzle out why a statement on tax cuts suddenly means our mortgage bill is going up.

The first thing to know is that the Bank of England is genuinely independent from the government, and has been since 1997. It has a few key mandates, foremost among them to try to keep inflation at around 2% – something with which it is clearly struggling.

When inflation is high, the Bank responds by raising interest rates, which is intended to take money out of the economy and slow it down. This works by making it more attractive to save, because returns are higher. It also makes borrowing and repaying debt more expensive. In some extreme cases, as in the early 1980s, high interest rates can lead to recession.

The Bank takes “excess” money out of the economy in order to bring down inflation. This is a contentious approach when inflation is caused by an energy supply shock, as few families feel as if they have much spare money right now. But this is the orthodoxy to which the Bank is required to subscribe, and interest rates were already rising before energy costs began to climb.

It is worth remembering that the Truss-Kwarteng emergency budget didn’t need to happen – the vastly expensive energy bill bailout had already been announced, and while markets didn’t love it, they generally felt it was necessary and accepted it without panic.

What spooked the market was announcing an additional £45bn of tax cuts – only £2bn of which have subsequently been reversed. This had two negative effects. One was to increase the cost of government borrowing (gilts), because markets were now concerned that the new government didn’t care about fiscal responsibility.

That £43bn of tax cuts means that the government is putting an extra £43bn into the economy – an economy which, from an inflationary perspective, already has “too much” money in it. The government is flooring the accelerator just as the Bank of England is stamping on the brakes – which means nothing good for the engine.

The Bank of England hasn’t actually met since the emergency budget, and it has not yet increased rates. But because the market expects them to do so, they’re acting pre-emptively. If you’re a bank and you know the cost of borrowing is going to go up next month, why lend money out at a loss this month?

This is exactly what mortgage lenders did. More than 1,600 mortgage deals disappeared from the UK mortgage market in the wake of the emergency budget, only for some of them to reappear at much higher rates.

Some people on existing fixed contracts are paying as little as 1% interest a year. New fixed-rate deals in the UK are now around 6% interest a year – a huge increase. Monthly bills will rise accordingly.

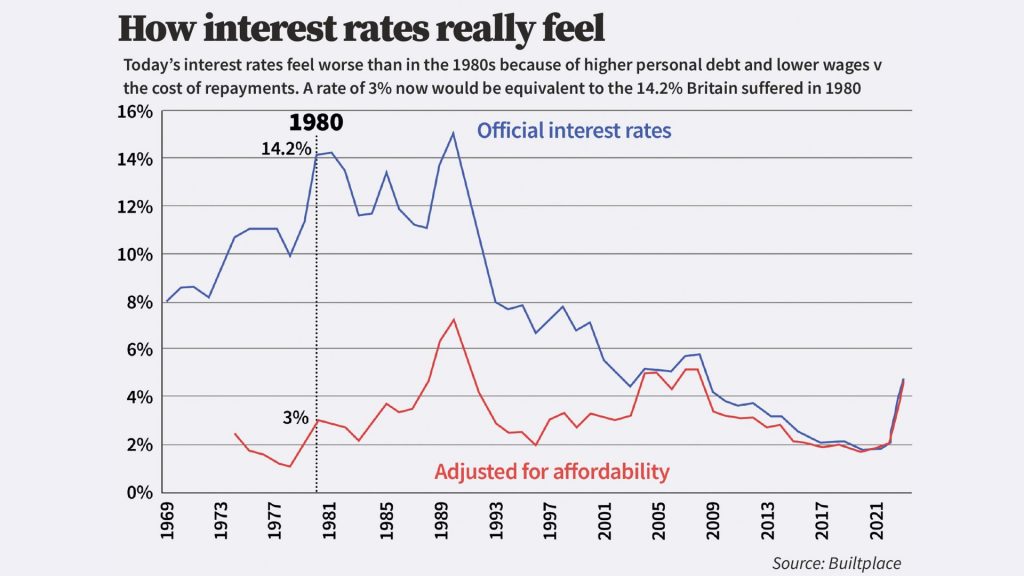

Older adults might shrug their shoulders, recalling that during the mortgage crisis of the early 1990s interest rates went as high as 15%. But this forgets that, at the time, house prices were much lower in both absolute and relative terms. Because house prices – and so mortgage debt – are so much higher now relative to wages, a mortgage with a 6% interest rate today is almost as crushing as a 15% mortgage back then.

There are around two million households that will need to remortgage in the next two years. They will all face a dramatic increase in the cost of their repayments, with some facing monthly repayments more than double what they pay now.

But the problem is even more acute than that: banks are obliged to make sure that borrowers would be able to repay their loan if interest rates went up even higher. Those repayment stress tests had, until recently, been considered to be too strict, requiring banks to check whether borrowers could afford their mortgage if the base rate went up by three percentage points.

That kind of rise seemed unfeasibly huge when base rates were down at 0.5%, but in reality have turned out to be too small – anticipated rate rises are now much larger than that. As a result, Nationwide is now using interest rates of 8% as its affordability test for most buyers, with a slightly lower threshold of 7% for first-time buyers.

They might not be the most sympathetic people on the market, but the problem is even more acute for buy-to-let landlords. Almost all buy-tolet mortgages are interest-only, with no repayment on the actual money borrowed – meaning that if house prices aren’t going up, the owner doesn’t accumulate any equity.

On top of this, while payments start lower they are much more sensitive to interest rate hikes. A buy-to-let owner might currently still have a mortgage with an interest rate of 1%, but may face a rate of 5% when they come to remortgage.

At 1%, a loan of £250,000 would accumulate £2,500 a year – meaning repayments of just over £200 a month. At 5%, that same loan accumulates £12,500 in interest each year – meaning repayments rocket to over £1,000 a month.

That doesn’t leave a typical owner with many options. They would certainly have to at least try to increase the rent. If they have equity in the property, they can try to sell – though not if the price has fallen so much that they’re in negative equity.

But renters looking to buy would face the same high interest rates that are forcing the landlord to sell. By contrast, a foreign buyer paying in cash gets the benefit not only of lower house prices, but also a fallen pound. For overseas cash buyers looking to become UK landlords, the current crisis is definitely an opportunity. For everyone else, it’s just a crisis.

There are numerous extra factors complicating the picture: shared ownership did not really exist as a model during the last housing crisis, but makes it much, much harder for people to move out of a property they can’t afford.

We also have the slightly bizarre situation of the government offering guarantees to banks on 95% mortgages to first-time buyers, at a time when those buyers could very easily become trapped in negative equity or by any future rate hikes. The subsidies are due to expire at the end of the year, but lenders, predictably, are warning that withdrawing them could bring an end to all offers for first-time buyers.

Anyone with the slightest memory of recent economic history will remember that it was mortgages that caused the last financial crisis – albeit that time in the form of bizarre financial products predicated on US subprime mortgages.

For the typical household, the mortgage is the biggest debt and the biggest monthly outgoing. People who have spent all summer worrying about paying their energy bills this winter are now having to worry about the mortgage as well – or about the rent next year.

This is a situation in which some sort of intervention will be needed to avoid a collapse. The question is how much of a battle that will prove with ministers. Protecting mortgages and house prices has been the defining mantra of the Conservative Party for decades, but this is a government that (often accidentally) torches sacred cows.

It will take time and finesse to find ways to avoid large-scale defaults and negative equity, especially in a way that won’t prompt further inflation and yet more interest-rate increases. That can best be achieved with planning and consultation – instead of letting the problem reach full-scale crisis point and dashing something together in a rush.

That all seems doable – until you remember who’s in charge.