Sometimes, a little reductionism can be a helpful thing. That’s certainly Adam McKay’s logic in his new Netflix film Don’t Look Up – which reduces the real-world morass around climate change to a much simpler extinction-level event: A meteorite.

Towards the end of the movie, all the general public needs to do to confirm the threat is simple, just look up. So inevitably, a populist US president starts a counter-slogan for her own purposes, don’t look up. Even the most obvious of threats can become politicised and divisive.

McKay’s occasionally clunky satire might be aimed at the problem of climate change, but for those alarmed by Omicron, it is likely to feel familiar. To some, the warning signs are just as clear as a visible meteorite in the sky: cases are rocketing, we know hospitalisations follow, self-isolation is putting thousands of healthcare workers out of action – and yet once again the UK government is not taking action.

There is every chance the most alarmed of us are right, and may even have been demonstrated to be right by the time this column goes to press. But McKay’s movie – and perhaps the alarmists – misses one crucial detail: so far in human history, the people announcing the end of the world have been wrong. There is a reason we don’t usually listen to doomsday cults.

In the movie (NINE KILOMETRE-WIDE SPOILER ALERT HERE!), they were right this time – just as those trying to sound the alarm early in 2020 were. But that doesn’t necessarily mean the most panicked are the most correct this time. In reality, the choices facing the government are much, much more difficult than they might appear.

In the military, generals are often warned against the dangers of fighting a previous war – over-correcting for earlier mistakes and over-adapting to the adversary they face.

This was certainly a problem which faced our public health experts in the early months of the pandemic. Too much of the UK’s response was based around flu, not coronavirus.

Estimates of transmission and severity were way out. Public health advice centred on handwashing – useful for flu, largely useless for coronavirus. More seriously, after the relatively minor hazards of SARS and MERS, experts dramatically underreacted to Covid-19.

But 2020 and the initial outbreak of covid is now the previous war. Omicron is the new one – and it’s possible for the pendulum to swing too far the other way.

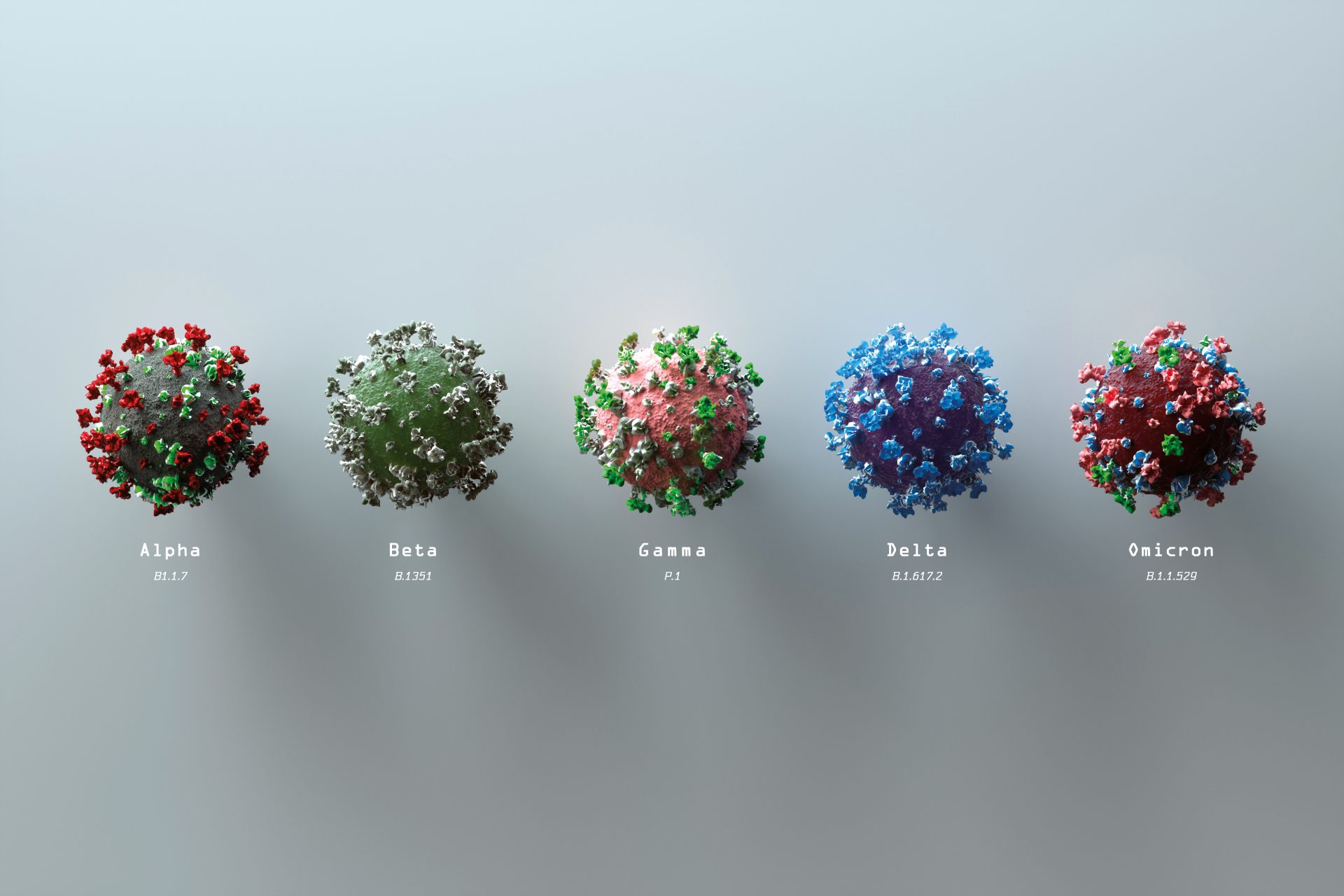

Omicron is massively infectious – perhaps the most infectious pathogen we’ve seen since measles. It seems quite able to beat vaccines. We have seen huge numbers of cases, and almost no one seems to believe it will be possible to contain it. It will spread around the world.

If the goal of restrictions was to stop people getting Omicron altogether, then those restrictions are surely doomed.

Instead, the logic appears to be trying to limit Omicron to a level where it doesn’t overwhelm the NHS – otherwise we could lock down entirely now, only to flood the NHS with Omicron cases whenever we reopen.

This is where the dramatic and alarming case numbers disconnect from our previous experience. Omicron has broken the daily records of case numbers to such a degree that we’ve had to change the axis on all of our covid graphs – and that’s likely to be an undercount.

Hospitalisation numbers, at least at the time of writing, are a more nuanced story though. They are certainly up, with the number of beds filled by coronavirus patients up 40% over the Christmas week – but still less than a third of previous highs. More reassuringly, ICU numbers have risen much more slowly, and deaths more slowly still.

Both hospitalisations and deaths lag cases, but we aren’t looking to track those even with the lags we know about from previous waves – whether because Omicron is milder, the population is vaccinated, or (most likely) some combination of the two, the previous alarming relationship between cases and hospital load is weaker.

Staff absence due to isolation is a problem, but hospital chiefs are saying in private, and with increasing confidence in public, that they are not overwhelmed at this point. There might still be a case for more restrictions than we have, but it’s not nearly as obvious as some people make out.

The government also hasn’t quite done nothing: Its key and most effective action has been a massive acceleration of the booster programme.

This, at least, seems to be working quite well – on numerous days, the UK has managed to give more than one million people their third dose of the vaccines. Given the effectiveness of boosters against serious illness, the omens are good. The guidance also appears to have worked, for now: people are travelling less, mixing less and wearing masks more. This half-hearted approach is not without its issues – not least for the hospitality sector – but it cannot be said to be totally ineffective.

We know now that the vague hope many of us once had, that we could just get shots and go back to normal, isn’t going to materialise.

Omicron will remain a thing even after most of us have our booster shots.

Given that, we need to have very clear reasons and goals for any new restrictions: what is reason enough to have one, what would trigger its end, and what would be different when it does end? Some advocates for restrictions are so sure their case is self-evident they have stopped trying to answer those questions and make those arguments, but they should make the effort. Support for restrictions has dropped, but the public can still be won over if the case is well made.

Devolved governments are not making the job of making a case any easier. To take a cynical view, it seems most of them are trying to do just enough to look stricter than the UK government, while not doing enough to incur major costs or trigger a widespread backlash.

The result has been regulations in Wales that ban Parkrun, perhaps the lowest-risk activity possible, for no good reason. We must do something, this is something, therefore we must do it.

Boris Johnson’s motivations against action are bad. We shouldn’t try to claim otherwise: he is afraid of his own backbenchers, especially as they may move to oust him later in the year. He’s afraid of his own Cabinet, and Rishi Sunak is clearly against spending any more money to compensate for restrictions – saving pennies, but costing the wider economy (and thus treasury receipts) pounds. And he’s aware that trying to sell the public on new restrictions when half his government broke the last set is a tough political job.

All of that is true – and all of that is bad. But the politics of messing up on Covid handling again and leading to thousands of deaths would be worse, so if push came to shove the government would be likely to re-introduce restrictions – and may yet consider some for January.

This time it might be worth trying to have more of this debate in public while we have the time – not with the shoutiest Piers Corbyn anti-lockdown fringe versus the most alarmist member of Independent SAGE, but with the plethora of engaged experts in between them.

Omicron is different from Delta and Alpha, and everything else that came before. The circumstances of the world on Omicron’s arrival are also very different. Omicron is many things, but it is not a clear and present world-ending meteorite hovering above our heads.

There isn’t, for this one, a single clear answer or a single clear course of action. To work out what to do next, we should probably thrash this one out – and maybe even consider that most heretical of concepts for 2022: that honest people can disagree.