When it comes to the forthcoming COP26 summit – billed by many as humanity’s absolutely last chance to avoid severe consequences of climate change – the UK government cannot be accused of pushing style over substance.

Unfortunately, that’s only because the ‘style’ side of the scorecard looks just as bad as the ‘substance’. Among the latest of a slew of COP26 stories in recent weeks was one in which the event’s corporate sponsors had written to the government with a litany of complaints about its organisation and planning.

It’s the kind of news story that startles on two different levels at once. The first is if you even can’t organise a conference, it seems optimistic to hope the substantive topic – engineering broad agreement to minimise catastrophic global climate change – has any greater chance of success. But let’s see how that plays out.

The second is simply that a momentous, inter-governmental, future-of-the-planet conference of this sort has corporate sponsors at all. This conflict of interests will sit oddly with future generations, especially if we fall anything more than a day late or a dollar short when it comes to the action our governments agree.

Boris Johnson has certainly worked to hype up the COP26 conference, putting prominent ministers and aides – including former press spokesperson Allegra Stratton – onto its team and loading the event with heady significance.

Only some of that is hype: the COP conferences aren’t about negotiating new deals (like the Paris Agreement), but are where countries negotiate actual actions and deadlines for cutting emissions. They’re supposed to be where the tough bit gets done.

Little about Johnson’s recent track record suggests monumental progress is likely. For his government to solemnly talk about long-term commitments and the importance of securing detailed agreements will chime oddly to anyone who’s watched him try to rip up the “oven-ready” Brexit deal upon which he won the last election.

The UK’s own progress on climate change has been somewhat patchy, too. While the UK is a leader in renewable wind energy, for example, the government initially supported plans to open a new coal-fired power plant in the North East, and has been tempted on several occasions to reconsider a ban on fracking for gas.

Johnson’s government is reportedly as divided on climate as it is on Covid-19, with ministers such as chancellor Rishi Sunak being sceptical about the need for major action on either, especially if it comes with short-term economic costs. It’s an underwhelming backdrop for success.

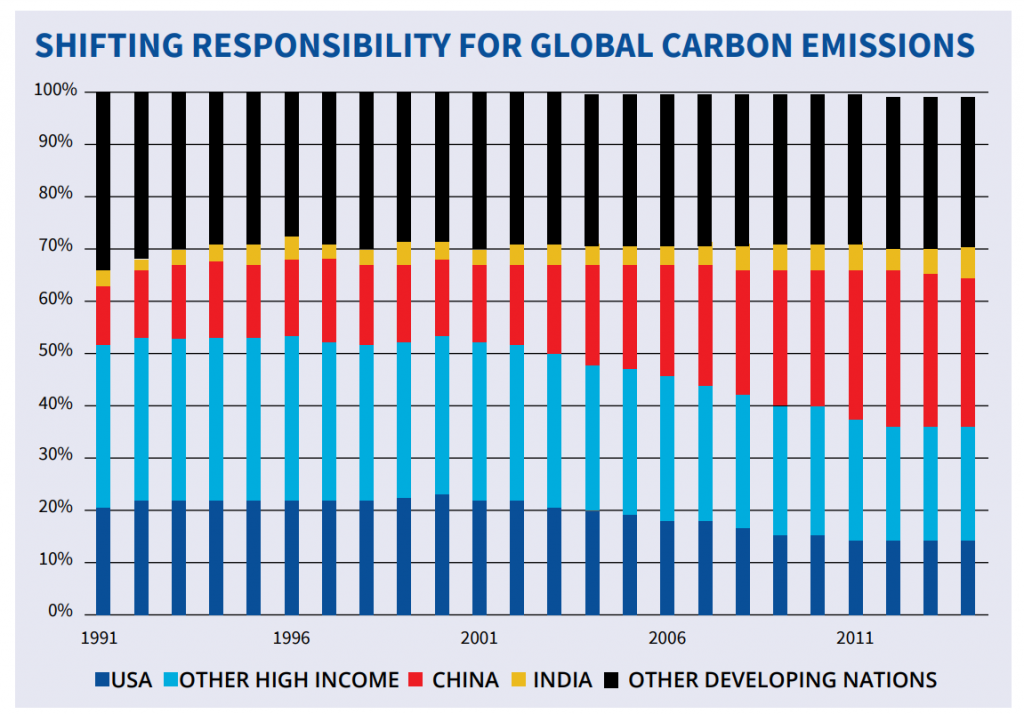

But the core problems could lie deeper. The reality of humanity’s next few decades in battling climate change is that the world’s most developed economies are not the most important.

Countries like the US and UK might still have higher emissions per capita than most less-developed countries, but these have been falling fairly steadily for years if not decades already.

This sets aside the thorny issue of apportioning climate damage according to the strict criteria of where the carbon is created. For example, Britain’s fast-increasing trade deficit with China (since Brexit the biggest importer into the UK with £16.9bn of goods imported in the first three months of this year, and at the expense of trade with EU imports which have fallen sharply) means it is our demand that, quite literally, fuels part of China’s carbon output.

At the same time, countries like India and China are seeing a higher share of their population wanting to buy into more of the staples of life taken for granted in richer countries – whether it’s heating, aircon, adding more meat to their diet, or buying more appliances.

It is an extremely tough and unfair sell to such people to ask them not to enjoy things we ourselves have taken for granted for decades.

Part of the issue here lies with a glib piece of left wing Western rhetoric that tackling climate change is incompatible with economic growth. That might connect well with a comfortable subset of the Western audience, thinking perhaps of cutting back on flights and taking the train rather than owning a car, and suchlike. But to a global audience finally looking at a future beyond subsistence farming or manufacturing for poverty wages, it is a devastating message – and an untrue one. Green tech and building can be good for growth and the environment. There can be ways to bring people on board.

Given the tough sell and the tough backdrop for the meeting in Glasgow at the end of the month, the UK as convenor of COP26 should have been putting absolutely every effort into supporting lower and middle-income countries through the year, building the trust and relationships to try to find the difficult compromises needed this autumn to get any kind of meaningful result.

This is not what has happened. At the unsurprising but difficult end of the scale is the decision of Chinese president Xi Jinping not to attend the talks in person. Though China will still send a delegation to Scotland, it is hard to miss the significance of them keeping their top player off the table.

Relations between the UK and China have been strained on many levels in recent years, including China’s decision to issue sanctions against several UK members of parliament over their comments on human rights abuses either against people in Hong Kong, or the estimated million or more Uighur people kept in detainment camps.

But rather than the UK being able to present itself as a developing and consistent ally, we have failed on this front too. We too stand charged with low morality and high hypocrisy.

In a time of global difficulty and devastation, the UK abandoned much of its role on the global stage. Having been respected as one of the best and most competent players in the aid world, with a firm commitment of spending 0.7% of GDP on overseas development, we cut that allocation in the globe’s hour of need to 0.5%.

This was billed as a ‘temporary’ cut, but sneaky measures taken aside from that by the Treasury will hardly reassure – the UK has decided to count its payments towards the IMF towards that 0.5% total, and has also managed to ensure the UK’s GDP calculation (and thus the percentage going on aid) will be artificially low at the next budget, as it will be based on out-of-date and overly pessimistic forecasts.

Coupled with the failure of the Covax programme – supported by the UK and most of the developed world – to actually get shots in arms in poorer countries, the UK will find it has little to no goodwill left in the bank when the world arrives in Glasgow. And that’s even before people potentially find themselves stuck in some of the rumoured chaos at the site.

Boris Johnson was, unusually, right to try to make COP26 into a big deal – to make it the focus of the year.

But it feels unerringly like he is thinking of it as some kind of Live Aid style festival, a chance to put on a show, say some nice things, and maybe to walk on stage with an oversized novelty cheque.

It is, on the eve of COP26, challenging to feel optimistic.