I realise that to TNE readers this may sound implausible, but trust me: I was deeply absorbed in Michael Ashcroft’s book about Jacob Rees-Mogg, skipping from one notable episode in the life of the so-called Honourable Member for the 19th Century to the next canny insight on the part of the millionaireTory-Party-donor-turned-hack-biographer, when this sentence pulled me up like a speed bump studded with sharp spikes: “In October 1997, he took part in a discussion on social class on the BBC Two programme Newsnight along with journalists Stephen Pollard and Will Self…”

Ashcroft then quotes at some length from an interview he had with my (alleged) fellow panellist in 2018. According to Pollard the discussion – moderated by the redoubtable Kirsty Wark – had been “perfectly amiable” until I decided I couldn’t stand Rees-Mogg, and said something to him that summoned a retort of this form: “Why should anyone take any notice of a self-confessed abuser of illegal drugs?” Apparently, I didn’t react well to this reference to the notorious episode earlier that year when I took heroin on the then prime minister John Major’s press plane during the election campaign.

Pollard’s account continues: “Throughout the rest of the discussion there was a palpable tension. I really did think Self was going to deck Rees-Mogg.” Nonetheless, according to him I kept a lid on it until the closing credits, whereupon: “Self got out of his chair and made as if to jump on Rees-Mogg. But Rees-Mogg clearly saw what was coming and before Self got to him, he was up, out of his seat and away. He ran out of the studio faster than you could imagine, like a very frightened rabbit. Self didn’t even bother going after him.” Despite which, my menacing behaviour has had a lasting effect on Pollard: “Since then, I have never been able to see Rees-Mogg without seeing his petrified expression as he thought he was about to be decked.”

I realise it may seem tendentious to the point of egregiousness to position myself so early on in this profile of Jacob Rees-Mogg centre-studio if not centre-stage, but I have a couple of serious points to make about this encounter – ones I believe bear significantly on any estimation of his character and importance. The first is: while I had in 2012 apparently recalled the encounter well enough to cite it in a squib that I wrote about Rees-Mogg for the Guardian’s Comment is Free strand, a decade later it had completely sunk back down into the loam of my semi-conscious, where it had mutated into quite a different recollection.

A recollection not – at least initially – undermined by Pollard’s account. I wondered if any of it really had occurred – at best he was guilty of hyperbole: in its heyday Newsnight may have been an arena of robust debate, but it was never this physically gladiatorial – if I’d actually threatened Rees-Mogg with violence I doubt I’d ever have been invited back on the programme again. (Which I most definitely was.) But it isn’t just that I don’t recall trying to lamp this man – who some view as a beacon of sincerity shining out over a darkling plane – at no point reading Ashcroft’s biography did I recall meeting him at all.

Rees-Mogg might well argue to this day that this just goes to prove the accuracy of his 1997 slur: self-evidently no one should take any notice of what a self-confessed abuser of illegal drugs says – given the abuser can’t remember what he says either, or even the context within which he says it. But unsurprisingly I take a different line: my amnesia regarding Jacob Rees-Mogg is an intermittent phenomenon – a sort of gift that just keeps giving; almost as if each time I recall him, I shortly thereafter happily forget he exists (at least in any direct relation to me) – and also one that’s further modulated by a false recollection that interposes itself between me and the ghastly truth: he does exist, and I have been in close proximity to him.

I certainly do recall having a run-in about class with an epigone of a journalistic dynasty – a preposterous popinjay, far lesser in his talents than his father. I also remember that my provocative statement – the one that summoned my interlocutor’s insulting retort – was about wearing cufflinks, which I figured as purely a matter of either being upper class or aspiring to be so. But what I have no memory of is that my opponent was Rees-Mogg – I thought it was Daniel Johnson, son of the veteran leftist-journalist-turned-rightist-historian, Paul Johnson. This leads me to my second point: it may be accorded a great benison to forget Jacob Rees-Mogg – but in that forgetting lies one of the core truths about this sublimely irritating man: he really isn’t that significant – and moreover, he’s far more of a type than he’d like us to believe with his relentlessly sui generis shtick.

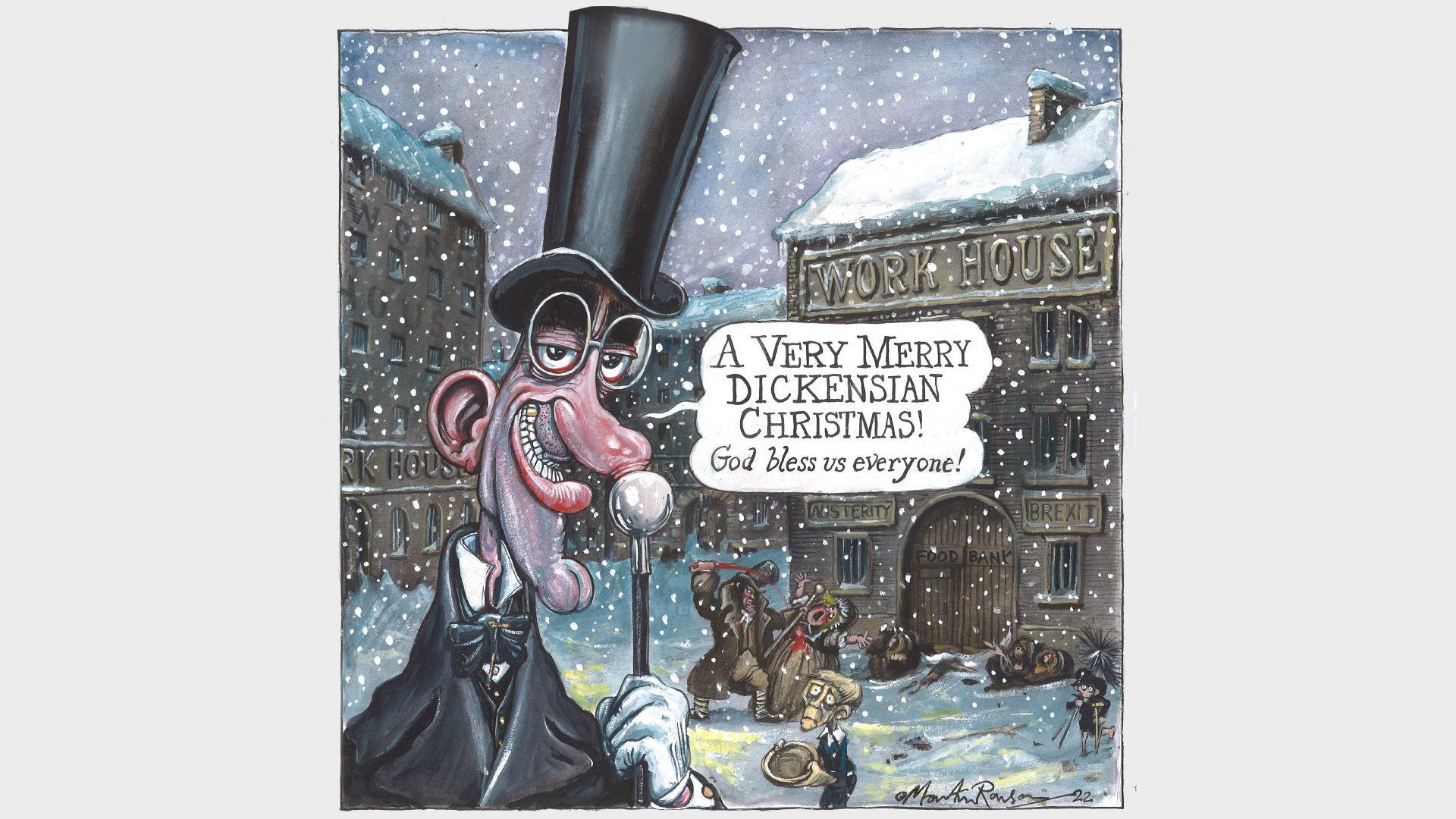

I bring you this as a sort of seasonal present: the multi-millionaire (indeed, near-billionaire) may be reclining on an ottoman before a vast open fire in his 17th-century listed manor house, with the same extraordinary insouciance he’s been known to exhibit in the House of Commons; lolling beneath a Christmas tree rivalling the mighty Norway spruce that lights up Trafalgar Square, while all around him are a multitude of expensive treats – whereas you are shivering in an unheated property deep in negative equity and contemplating the Malthusian gap opening up between your income and your entirely nugatory expenditures; nonetheless it is he that’s yesterday’s man, while undoubtedly you are the person of the future. True, in the short-to-medium term that future may not appear too welcoming; however, this is only the darkness before radiant dawn – one illuminating a brave new world in which Rees-Mogg’s political career is dead in the water, together with the cod-ideology he has personified.

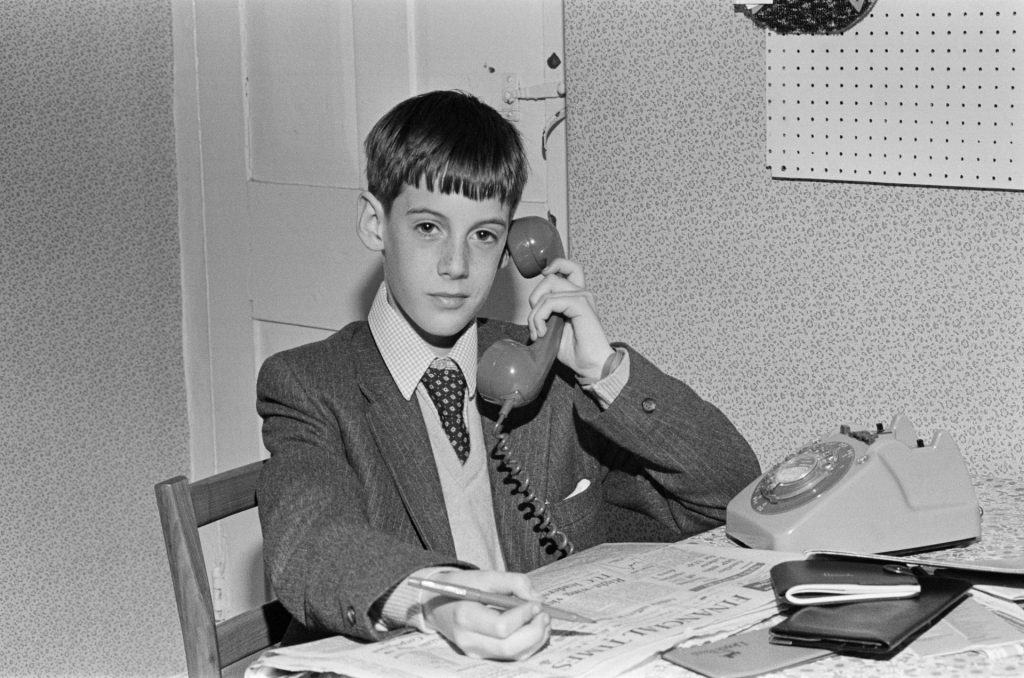

For this much is true: insofar as the Brexit project was always a psychodrama integral to the Conservative Party, so the rise of Rees-Mogg has been predicated on this psychosis: a belief in a uchronia rather than a utopia; a time in the past when social relations were organic, and the lower orders – that’s me and you – happily accepted the rule of our betters. Integral to this is the myth of how much better Rees-Mogg is than the rest of us (or, at any rate, the rest of the Brexiteers who believe in such bullshit): posher and richer, certainly – yet also smarter and more able, such as to neutralise any suspicion that his position and wealth is in any sense unearned. Is this Rees-Mogg not the child prodigy of investing, who as a picayune shareholder nonetheless fearlessly bearded the chairman of the giant conglomerate Lonrho at an annual general meeting when only 11 years old? But before we follow the money let’s just consider the class.

During the 2015 election campaign his mother, Gillian, who was helping him canvass, told a reporter from the Independent: “We’re not posh. All that stuff they write about him? About double-breasted pyjamas? Come on. So he went to Eton. What 13-year-old boy chooses where they go to school?” Lady Rees-Mogg may have been spinning a line here – yet perversely, it’s also the truth. The Rees-Moggs are Somerset gentry – true enough; and, courtesy of the first Rees-Mogg born with the double-barrelled name (Jacob’s great-great-grandfather, William, a solicitor and successful businessman), have been relatively well-to-do for several generations – yet The fake they are emphatically minor gentry, without a whiff about them of the aristocratic.

Of course, social snobbery is the ultimate narcissism of small differences, with infinitesimal alterations in dress and demeanour regarded by their cognoscenti as if they signified major hierarchical distinctions – but beneath such manifestations of class lies its true ideological basis: genealogy. An acquaintance told me of a visit he paid to the erstwhile secretary of state for business, energy and industrial strategy’s stately pile for a meeting: “There were all these expensive cars parked on the gravel apron in front of the house – Bentleys and Rolls-Royces; and they all had RM personalised number plates. No truly posh person would ever be so vulgar…”

My informant is well-born enough himself to know what he’s talking about when it comes to such gradations – yet a far more significant class indicator than personalised number plates and tailor-made pyjamas is the name Gillian. It’s not an aristocratic one – anymore than is Morris, Lady Rees-Mogg’s maiden surname. Indeed, not only did Jacob’s father – the one-time editor of the Times, William Rees-Mogg – marry down, but William’s father, Fletcher Rees-Mogg, married down before him. Jacob Rees-Mogg’s own fervent Catholicism – a religious faith that, with its conservative ethics, amplifies his own stentorian moral position – only derives from his grandmother, Beatrice, an Irish-American actress. Having myself at one time been married into a posh Catholic family with Somerset links (my first wife’s great-aunt is Jacob Rees-Mogg’s godmother), I know a little bit about not only the subtleties of upper-class status, but also that curious Catholic subset of them.

My ex-wife’s family owe their Catholicism not to being Reformation recusants – but are rather so-called Farm Street Catholics: posh Anglicans who converted in the first few decades of the 20th century. The ultimate parvenu associated with this group is Evelyn Waugh, whose Brideshead Revisited depicts the starry aristocratic Catholic realm he – in common with Rees-Mogg – would have liked as his birthright. (Waugh, who was a publisher’s son from north London, was such a precocious snob that in childhood he used to walk up the road from the family home in Golders Green, so that his letters would receive the tonier Hampstead postmark.)

It’s this aspect of Catholicism: a sort of upper-middle-class bypass operation, whereby the patient is sutured directly to the likes of the Duke of Norfolk and other aristocratic recusant families, that so shapes Jacob Rees-Mogg’s imposture. In his justifiably panned 2019 book, The Victorians: Twelve Titans who Forged Britain, Rees-Mogg chooses as one of them Augustus Pugin, the co-designer of the current Palace of Westminster.

It’s undoubtedly Pugin’s Catholicism that recommends him to Rees-Mogg quite as much as his Neo Gothic restyling of the spiky mother of parliaments – but the Neo Gothic is itself the reification of Catholic emancipation in the 19th century: a visible, tangible harkening-back to the pre-Reformation. Rees-Mogg’s public image is like a Neo Gothic edifice: seemingly of medieval provenance – but really a far more recent bit of fakery.

But if he doesn’t have the genealogy commensurate with his lordly affectations, he does now at least possess the requisite stately pile. And indeed, inasmuch as he’s always been widely viewed as his father’s creation – a sort of Mini-Me-Mogg, although William wasn’t so much Dr Evil as Dr Establishment – his acquisition of Gournay Court, the aforementioned pile, is evidence of an inter-generational obsession with grand houses.

One that his father dates to the Victorian era, when his prosperous namesake demolished the relatively modest old family seat, Cholwell House, and replaced it with an uglier Victorian mansion. This house, and its associated estate, didn’t survive his father’s demise, and William Rees-Mogg then bought the large Palladian house Ston Easton in 1964, and hung on to it until the end of the 1970s. It’s in these impressive surroundings – ones which, William admits in his memoir were well beyond his means – that little Jakie (as he’s known in the family) was brought up. No wonder he has suffered from folie de grandeur ever since. His marriage to the staggeringly wealthy – and stratospherically posh – Helena de Chair, in 2007, enabled him both to buy a suitable setting for his snobbery, and to affect it with some conviction since his numerous progenies will – so long as they aren’t downwardly-mobile – be to both manner and manor born.

William Rees-Mogg is, as I say, widely seen as Jacob’s most significant influence – but he never affected his son’s aristocratic hauteur. It’s amusing to view a 1971 interview with him, since his interrogator, Cliff Michelmore, has a markedly posher accent than the Times editor. Nevertheless, while William cleaved to his Catholic faith, and attended the less posh Charterhouse public school, rather than Eton (where his son went), the story of his life reads as if he were laser-targeted on the very apexes of power, money and privilege in the Britain of the latter half of the 20th century. To read his memoir is to encounter at every turn another entrée: as Jacob said in a valedictory piece he wrote about his father for the Mail on Sunday, after William’s death in 2011: “He knew every prime minister from Eden to Cameron […] He met popes, presidents, princes and even pop stars.” The latter being a reference to Mick Jagger, whose drug-taking Rees-Mogg père was considerably more relaxed about than his son was about… mine.

For both men public school was a synecdoche of the establishment – the roll-call of illustrious contemporaries is extensive – as was Oxford University, where they both became star debaters in the union. Both Rees-Moggs were outgoing, both formed new politics societies at their respective alma maters – quite obviously as part of their own overriding ambitions for political power, since it enabled them, as neophytes, to encounter those who already wielded it. But in Rees-Mogg senior’s case, after two unsuccessful attempts to win a parliamentary seat, he chose journalism in lieu of a political career. Which is why, rather than belonging to the aristocracy, his son is a scion of what we might rather call the hackistocracy. (This explains why in my hazy recollection I substituted Daniel Johnson for him.) The hackistocracy is even more clannish than the aristo one – and Rees-Mogg lunches with the poshest hackistocrat of them all, Rupert Murdoch, whenever the latter is in London. Indeed, if you wanted to neatly sum up their respective careers, you might say that William attempted to parlay journalistic power into political influence, whereas his son has merely done the reverse: pumping what political power he’s possessed into an inflated public image.

This being noted: the image-creation began a long time back, as did the aristocratic affectation. Little Jakie’s appearance at that Lonrho meeting was a function of his having bought a handful of shares using his pocket money – and it led to a disproportionate amount of media coverage: a newspaper interview, and even a short documentary film about him. By the time he reached Eton – let alone Oxford – his persona was firmly in place; modelling himself, in part, on the PG Wodehouse character Psmith (Rees-Mogg is predictably a great Wodehouse fan), he aimed at all times to project a highborn insouciance. To be fair, this includes what everyone testifies to as impeccable politeness, and a personal manner devoid of any snobbery. But then, what else would you expect from such a smooth operator? The philosopher Hobbes observed that “charity relieves the rich man of the burden of his conscience”, and you could extend this maxim by observing that great politeness temporarily blinds the less well-off and connected to the privileges of the rich man.

But why is Jacob Rees-Mogg so very rich? The assumption is that he must be very good at making money – certainly his father defers to him as such in his own memoir. But then that’s the same father who neglects to mention that Jacob’s first job in finance – with his namesake Jacob Rothschild’s bank – came through his father. William was both a friend of Rothschild and a non-executive director. Jacob’s second job in finance, with Robert Lloyd George’s fund management company in Hong Kong, was also a function of paternal connections. Indeed, I suspect if you performed open-heart surgery on him, you’d find the word “nepotism” appliquéd to Rees-Mogg’s aorta.

Rees-Mogg didn’t shine at Rothschild’s, and while at Lloyd George’s he made at least one serious error that cost the company a great deal of money. Moreover, in the bull market of the 1990s it was pretty damn easy to make money as a fund manager, while in the 2000s, when he became head of Lloyd George’s Emerging Markets Fund, it notably underperformed in comparison with similar ones. Indeed, probably the only really inspired thing he ever did in his City career was to stab Robert Lloyd George – who had behaved entirely graciously over his mess-up – in his pinstriped back by fomenting a rebellion among his employees. Rees-Mogg’s grouse – as it was at the very beginning of his career as an investment specialist – was that he, personally, wasn’t getting sufficient remuneration. Having failed to take over Lloyd George’s company, and with the assistance of the notorious hedge fund manager Crispin Odey (most recently in the news for having shorted the pound during the shortlived Liz Truss regime), ReesMogg left the firm, taking with him two brilliant financiers: the now oddly ennobled Dominic Johnson and the fund manager Edward Robertson. Johnson says of his friend and now former colleague: “Jacob’s great for the business – we have a far higher profile than we ever would if we didn’t have him involved,” suggesting that financial wizardry isn’t really his forte.

A point underlined by sources I have in the industry who knew the firm well, and who say that Rees-Mogg was a decent but unexceptional investor, and that the success Somerset Capital achieved came almost entirely after he stepped back from the business and was down to the work and decisions of others (who would also baulk at the suggestion that it was Rees-Mogg’s own investing acumen that made the firm highly profitable). If Rees-Mogg deserves real credit for the firm’s success, it is primarily for the equitable business model that he and his co-founders created, in direct contrast to Lloyd George whence they had just jumped ship.

Furthermore, he was only at SCM full time for three years before entering parliament – and when he was appointed leader of the House of Commons in 2019, he stopped working for it altogether. Compounding this impression of opportunism rather than professionalism, the very impetus to leave Lloyd George and form his own company, was, some say, his marriage to Helena de Chair, and the vast fortune it brought him.

Ashcroft titles his biography of Rees-Mogg Jacob’s Ladder – the obvious reference is to the Biblical patriarch’s dream of a ladder reaching to heaven, a vision that has been interpreted as an affirmation of his commitment to upholding the Abrahamic religion. I don’t for a second doubt Rees-Mogg’s religious faith – and neither do I believe him to be self-consciously duplicitous: rather, the milieu that has made him what he is, is typified by such a contradiction between political ideals and economic realities that it cannot help but produce such bizarre phenomena as arrant hypocrites who genuinely believe they’re close to sanctity. Really, the “ladder” of the title should be seen as referring to the huge number of ladders made available to this serpentine character; for my feeling is that without them he probably wouldn’t have achieved that much at all: he is clever, certainly, but no great intellectual – as a very cursory reading of the piss-poor The Victorians will confirm; he is charming, certainly, but while – as Jean Cocteau sagely observed – “charm is a quality that enables its possessor to solicit the answer ‘yes’ without even posing the question”, you have to be able to get those yeses from the rich and powerful in order to monetise your personal magnetism.

Just one of the many ladders Rees-Mogg has benefited from is the redrawing of the borders of the constituency he now represents – before this was done, he quite likely wouldn’t have been elected, as it still contained quite a bloc of less affluent voters on the outskirts of Bristol. But if this was a help, Brexit was an even greater one. Some – notably Andy Beckett in a long profile of Rees-Mogg he wrote for the Guardian in 2018 – have seen his father’s influence as not only pragmatic, but also deeply ideological. Beckett draws our attention to William’s 1997 book The Sovereign Individual (co written with the American investment specialist James Dale Davidson – another of Jacob’s ladders, given that he organised an internship for him with a prospective Republican presidential candidate in 1988), in which the former Times editor – latterly dubbed “Mystic Mogg” by Private Eye – argued that the coming age of cyberspace would mean individuals could transcend their nation states, and become their own rulers, hence the title.

Private Eye’s epithet is a little unfair – given that Rees-Mogg and Dale Davidson also foretold the invention of something very like cryptocurrency, and even made a pretty good guess at what the mathematics underlying it would turn out to be. But the Beckett hypothesis depends for its accuracy on something I don’t believe to be the case: that Rees-Mogg Junior is a cynic, and all his patriotic blether is just that. His father – while remaining institutionally and emotionally welded to the Conservative Party – was always more ideologically latitudinarian: a Keynesian before he was a monetarist, and a pro-European before he was an anti-one. In his memoir, Rees-Mogg Senior writes with some passion about how his conservatism relates to his home county of Somerset – but the paradox is that it’s this connection between physical location and political dispensation that he correctly foresaw the demise of.

And actively encouraged: William wrote that he initially supported the EEC (as it was), precisely because he felt it represented a freer market – then turned against it for the self-same reason. Yet free markets and free trade are, of their very essence, transgressive – and ultimately destructive – of national boundaries. That his son doesn’t quite understand this is, I believe, grounded entirely in aspects of his character he doesn’t share with his father.

Much has been made in the past of how close Jacob Rees-Mogg’s relationship has been with his former nanny, Veronica Crook. She’s been known to canvass for him at elections – and has gone on to be nanny to Jacob’s own children; when he was at Eton, she came weekly to change his sheets for him: he doesn’t do domesticity in any way, shape or form, while retaining other obviously neotenous characteristics now well into middle age. A friend quoted by Ashcroft says of him: “He hates foreign food. He hates bananas. He hates showers. He hates hotels. He is not a linguist. He seldom, or never, even holidays in Europe. He genuinely believes England, not Britain, is the best country in the world and that Somerset is the best county in England.”

This seems pretty childlike to me, and quite at variance with his father’s rather more cosmopolitan tastes. All the hard-line Brexiteers seem to have this mushy core of juvenile chauvinism, one that metastasises into their cancerous patriotism – indeed, Boris Johnson’s love of foreign food, showers (essential after a clandestine cinq-à-sept rendezvous), hotels (in which to have the aforementioned rendezvous), speaks of a far less cloistered and immature psyche than Rees-Mogg’s, and goes some way to explaining his agonising over whether to back Leave before his opportunism got the better of him. Really, Boris’s own young fogey act has been upstaging Rees-Mogg’s for decades now – and if it were not for the latter’s sea-green incorruptibility as a Brexiteer, it’s doubtful he’d have gained anything like the profile he has.

Yes, Brexit made him – and Brexit will bury him as well. Jacob Rees-Mogg has now been a minister in two Tory governments that have imploded, and you don’t have to be Lady Bracknell (or even plain Mrs Bracknell) not to see this as carelessness. While he may have flirted with putting his hat in the ring after he and his subaltern cronies in the European Research Group (ERG) drove Theresa May from office, in the end he backed Boris, probably realising that the increasingly socially-liberal British electorate would never stand for a prime minister who believes that gay people – along with those who have had abortions – will burn in hell. And since he struggled free from the wreckage of the Truss administration, there’s been a rising note of desperation in the way he’s carried on about the advantages Brexit is soon to bear – he’s on the record far too much for him ever to resile from this arrant nonsense.

I do realise that as a hack myself – and moreover one who’s had on-screen run-ins with not just Jacob Rees-Mogg, but also with another chairman of the ERG, the ridiculous political pipsqueak Mark Francois (a working-class Tory cast in exactly the sort of deferential mould Rees-Mogg would love to manufacture in bulk) – that my Europhile readers may take my writing-off of his political career with a generous pinch of sea salt. However, if someone looks historical, sooner rather than later he’ll definitely be… history. In an interview with the Catholic newspaper the Tablet, Rees-Mogg vouchsafed that the essence of his Catholicism is the Resurrection – but that means Jesus’s, not his.

Will Self’s Why Read: Selected Writings 2001-2021 is published by Grove