After almost 50 years in the Labour Party, I could be in danger of missing out on my gold watch.

As someone with more than a passing knowledge of Labour at both a local and national level and with some academic expertise in politics and polling, I have grown increasingly despairing as I have watched Labour lock itself into ever more (seven at the last count), self-imposed and unnecessary, policy binds.

We begin with the last election and Labour’s unwarranted EU pledges – three in all.

For the two years prior to the election, almost all the responsible polling was showing two unmistakable trends – that Labour was holding a consistent lead of around 20% and that the public’s enthusiasm for Brexit had waned, almost to the point of irrelevancy.

And yet, throughout the pre-election period, then through the campaign and into government, the party leadership (against the clear wishes of its membership and the inclination of large swathes of its potential voters) stuck to its anti-EU narrative of the three red lines – no return to the single market, no to the customs union and no to free movement for young people.

These were all designed to recapture the allegiance of the patronisingly named ‘hero voters’ – the supposedly large swathes of traditional Labour voters in the so-called ‘red wall’ seats who in 2019 had deserted Labour and voted for Boris Johnson’s Conservatives, presumably because of their fear of a Corbyn-led Labour Government.

The other vulnerability mistakenly detected by Labour strategists was tax policy and again we saw the same rush to create unnecessary red lines – no rises in income tax, national insurance or VAT, plus a new self-imposed fiscal rule: borrowing only for investment purposes not for current expenditure.

The logic was that by eliminating what the leadership took to be its key vulnerabilities, its path to victory was assured. But a review of what was actually happening to the electorate during this period demonstrates just what a series of unnecessary, and subsequently damaging, moves they were – and now we’re paying the consequences.

An IPSOS poll conducted immediately after the last election revealed that just 12% of those traditional Labour voters who had voted Conservative in 2019 switched to Labour in 2024. In other words, just because Labour committed itself to a pro-Brexit/anti-tax stance and won a thumping victory, it did not follow that it was because of these policy commitments that Labour won such a thumping victory. Correlation is not necessarily causation and in the case of Labour and the ‘red wall’, this turned out to be the case.

When Tory to Labour switchers were asked their main reasons for switching, our relations with the EU did not make it into the top ten issues that voters took into consideration when casting their vote. Even for those voters who switched from Conservative to Reform, the EU/Brexit was only the fifth most important issue.

In other words, Labour’s belief that its stance on Europe was a major negative factor for Labour’s ‘hero voters’ turned out to be a myth – its pledges of undying commitment to the Brexit deal played no significant role in voters’ electoral choices.

The other issue that led to the additional four red lines was fear of Labour’s claimed predilection for raising taxes – hence the declaration that there would be no increase in income tax, national insurance or VAT within the lifetime of the next Labour government, to which was then added the self-imposed fiscal rule of only borrowing to fund capital projects.

It was another entirely unnecessary strait jacket. The Ipsos poll asked the 2019 cohort of former Labour voters who had switched to the Conservatives but in 2024 were switching back to Labour; they found that ‘managing the economy’ was only the fifth most important issue for them.

Even well before the election campaign (in April of last year) a major poll of 18,000 voters, conducted by Electoral Calculus, found that just 11% of those who intended to vote Labour in the coming election were 2019 Tory voters (and an even larger YouGov poll, taken after the election, put the figure at just 10%). Voters’ concerns about tax was, according to Electoral Calculus, only number ten in their list of priorities – and the EU/Brexit issue did not even make it into their issues top ten.

In other words, well before the election, it was clear that the party’s declared policy commitments about the EU and taxes were nowhere near the top of the concerns of those former Labour voters who were about to switch back to Labour after voting for Johnson’s Conservatives in 2019.

Of course, what people tell pollsters about their motivation for their party choices is not a science. Voters make their electoral choices for a whole range of reasons, including tactical voting, past voting and the influence of family, friends, the media and so on.

Their answers about their motivation to vote are generally a rationalisation of this complicated matrix. Notwithstanding, other than through focus groups (which are not a useful way of measuring large-scale trends), properly conducted opinion polls are the best measure we have.

So the big question is why, in the face of all the evidence, did Labour take such a defensive stance in the run-up to the last election and beyond?

Clearly, under Starmer (as is put at its starkest in Tom Baldwin’s semi-official biography of the PM), the leader’s sole focus was on winning. It was not just his top priority (as it clearly should be) but it came to obscure all other considerations.

As the figures above demonstrate, just as Starmer and his teams were mapping out their political priorities, those of the electorate were changing – indeed had changed.

That Labour failed to take this changing landscape into consideration, and apparently still do, is a massive political failure and a serious indictment not just of Starmer’s leadership but of the competence and vision of the team he has chosen to surround himself with.

The political game is sometimes likened to a game of chess in which the moves and countermoves of the opposition party and parties is an important strategic consideration. But, unlike chess, the game of politics is not played on a two-dimensional chessboard but in a constantly changing, multi-dimensional national and global environment (Trump’s current tergiversations in the White House being the most recent exemplar).

Politicians, and their advisers, have to be fleet of foot, ready to change direction as the political environment changes. In the oft-quoted words of John Maynard Keynes: “When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?”

The ‘facts’ about the public’s views on Brexit and tax have changed, so surely, in the face of Trump’s tumultuous attack on the world’s trading system, it’s time for Sir Keir and his party to change their mind too?

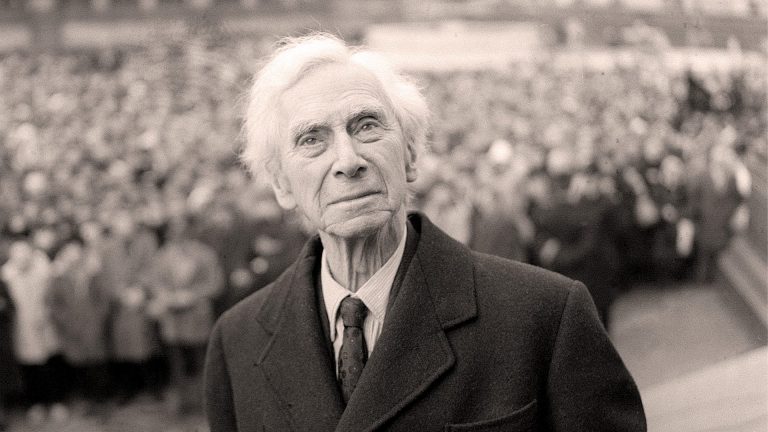

Ivor Gaber is professor of political journalism at the University of Sussex. He held senior editorial roles at the BBC, ITN and Channel 4.