Politics in Westminster may move at a breakneck speed according to Nadim Zahawi, but in Belfast it is still Groundhog Day. One output of three British prime ministers in three months is two Northern Ireland elections in seven months and barring a miracle, we will go back to the polls on December 15 to vote for another Assembly that may end up never sitting.

Stormont has been collapsed since February, when the Democratic Unionist Party pulled its first minister out of government in protest at the Northern Ireland Protocol, which prevents an Irish land border by creating a customs border in the Irish Sea. Unionists believe that this border undermines their position in the union and breaches the terms – and spirit – of the Good Friday Agreement, signed 25 years ago next April.

For all the talk of free trade and economic zones, the ongoing dispute that has stalled devolved government has given rise to an irony-free zone, in which DUP politicians express frustration about disruption in Downing Street, while continuing to refuse to take their seats in Stormont in protest at the Protocol. The Northern Ireland secretary Chris Heaton-Harris has been involved in talks to bring an end to the deadlock, but both unionists and nationalists recognise that Rishi Sunak has many other urgent issues in his prime ministerial in-tray taking precedence.

For the unionists, an issue of trust is fundamental – trust that they say has been broken by first Theresa May’s backstop and then Boris Johnson’s Protocol. For nationalists, intransigence and the ongoing UK-EU-Dublin psychodrama stirs thoughts of the border poll that might one day deliver a reunited Ireland.

Yet in the horrific story of the explosion that killed 10 people at a service station in Creeslough, Co Donegal in early October, a smaller narrative emerged that spoke volumes about the true nature of the relationship between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland – one that is inextricably linked, symbiotic and well-intentioned.

Among the emergency responders searching for survivors beneath the rubble were members of Northern Ireland’s Fire and Ambulance Services and its charity-funded air ambulance.

As the death toll rose over the weekend of October 7 and 8, this joint endeavour to save lives brought a scintilla of solace amid devastating tragedy. Of course, it wasn’t surprising – this is how it always works, and how the vast majority of people want it to work. But post-Brexit, when relations between the British and Irish governments have been increasingly fraught and those between nationalists and unionists increasingly febrile, it was a reminder of enduring bonds.

Back on the political stage, there is anger. Much of the DUP’s electorate is frustrated by its ineptitude and cack-handedness – the failure to anticipate the pitfalls of backing the Leave campaign and then, despite holding the balance of power at Westminster during much of the Brexit negotiations, ending up with the Irish Sea border which was always its nightmare. The reality has destabilised unionism to such a degree that the delicate balances of the GFA no longer function. The chronic lack of alignment between London and Dublin on these issues is a symptom of multiple errors of judgement that won’t right themselves – they need to be confronted head-on and corrected.

A series of unnerving “historic firsts” has fed unionist insecurity and angst. Many feel the ground is shifting beneath them. Old certainties are crumbling. Demographics seem to be turning against them. In the Northern Ireland Assembly elections in May, Sinn Féin became the largest party for the first time, enabling it to appoint the first minister.

Last month the Northern Ireland census results revealed that there are now more people from a Catholic background (45.7%) in Northern Ireland than Protestant (43.48%). It’s the first time in the 101-year history of a state that was designed to guarantee a unionist majority.

Even a visit by the new King was troubling. What ought to have been an occasion for loyal subjects to mourn the late Queen and herald their new monarch turned bizarrely into a PR win for the separatist Sinn Féin. The republicans recognised the historic moment and embraced the role of putative first ministers and Speakers of the House to represent all sides in a civic fashion.

Footage of King Charles III meeting politicians at Hillsborough showed him sharing a warm and good-natured exchange with Sinn Féin first minister-designate Michelle O’Neill. In contrast, Sir Jeffrey Donaldson, leader of the DUP, was caught on camera looking uncomfortable and socially awkward. Odd as it may seem, such optics matter. Being able to look relaxed and confident, even while others are trying to make you feel isolated, has been the art of politics for centuries. Even the new King’s namesake, Charles I, asked for a warm shirt so as not to give the impression he was trembling with fear at his execution. That sangfroid does not come easily to unionism.

As with so much else in Ireland, nothing is as it seems. Analysis of all the above, especially the census returns, reveals a more complicated picture than the headlines suggest.

The narrative appears to be that Sinn Féin will take power in the south at the next election in January 2025. This winter the office of Taoiseach, currently held by Fianna Fáil’s Micheál Martin, passes to Fine Gael leader Leo Varadkar, the other partner in the coalition. The shape and competence of that administration will determine much of what happens when the polls next open.

Martin proved a more nimble force in relation to unionist opinion than most of his predecessors, but the paradox has been that Fine Gael, traditionally the anti-republican party, has had to recognise the electoral pull of Sinn Féin’s unity agenda and has recent history of being peculiarly tin-eared and bullish in pursuing a nationalist timetable.

Civic society in Ireland – or republican parts of it – has mobilised with what is seen as the approaching moment for “Irish unity”, or territorial gain at least. A recent gathering in Dublin entitled “Ireland’s Future”, while not quite mustering as big or as influential an audience as hoped, nonetheless gathered around 5,000 attendees and helped to centre the “unity” ambition even at a time when the cost-of-living crisis and insecurities over energy, climate and war threatened to dominate.

With unionist parties opting out and the middle-ground Alliance Party staying away – arguing that politics shouldn’t be binary – critics described the event as a talking shop among nationalists and more of a pro-unity rally than in-depth focus on how, for example, separate health and education systems would be merged.

But one keynote speaker from a Protestant/unionist background was the actor James Nesbitt, who told delegates that the term “Union of Ireland” might be more palatable than “United Ireland”. He was unsure about the arguments advanced by nationalists, but was open to an informed discussion.

That the conversation is taking place at all has spooked unionism. With the dysfunction that has exasperated its electorate, it has been slower to mount a similar drive to talk up the merits of the union. Finally, last month saw the Belfast launch of the UK Together movement, which is being headed by Arlene Foster, the former first minister.

For all the gung-ho response to the census headlines, it is important not to read too much into the religious headcount. There was little in the statistics to prompt Heaton-Harris to ponder calling for a border poll any time soon.

Pro-unity campaigners seized upon the headline figure of a Catholic majority, as well as the fact that the number of people identifying as British, either in itself or in conjunction with other identities, has dropped from 48.4% in 2011 to 42.8% now. Those identifying as “British only” has fallen from 40% a decade ago to 31.9% today. But this being Northern Ireland, those figures carry considerable caveats.

Those identifying as “British only” were 32%, as “Northern Irish only” 20%, and though almost 46% of the population is Catholic, only 29% identified as “Irish only” – the latter was particularly striking given the surge in nationalist confidence. Is that really the sort of figure that suggests a vote for Irish unity is imminent?

The big story is the surge in the middle ground. In the May elections, the undesignated Alliance Party won 17 seats, more than double the number it held after the 2017 election. The 20% who see themselves as “Northern Irish only” are seen as further evidence of this growth. In effect, there are now three main groupings – British, Irish and Northern Irish.

It is this latter grouping that could potentially be the deciding factor in any future border poll. In other words, politics and wellbeing and stability unsurprisingly will trump any kind of perceived racial or cultural allegiance. Making Northern Ireland economically prosperous and peaceful, a place where everyone can feel at home, is key – and that will require pragmatism on the Protocol.

The census is indeed telling a story, but it is chock-full of that stuff everyone from ideologues to bullies to revolutionaries simply hates – nuance.

And the irony is that the riches to be gained by recognising this are all on the unionist side. The question is whether or not unionism can take advantage of the opportunity. The Democratic Unionists have a serious problem, in that it is clear now that the coup that ousted former leader Arlene Foster in summer 2021, replacing her with conspirator and party fundamentalist MLA Edwin Poots – who himself was defenestrated within weeks by Donaldson – has not defined a settled pathway to a unionist future for Northern Ireland.

Unionist insiders are bullish about an imminent election, believing unionism is united behind Donaldson. Its “back to the wall” mentality may well come into play again, but none of that can disguise the wider dissatisfaction with the DUP for getting it so wrong over Brexit. Donaldson delivered a rousing speech at his party’s annual conference in Belfast in early October, but the mood in the hall was described as downcast, with members unsure as to what the future may hold.

The party remains riven with internal division. Poots, whose Young Earth Creationists was mocked – he believes the planet is only 6,000 years old – was the shortest leader in its history, but paradoxically continues to enjoy a high profile and leads the way with inflammatory rhetoric.

Recently he cautioned against any delay in the Protocol bill passing through the Lords, saying that “unless something radical happens and the EU decides to become a bit more realistic, [US president Joe Biden] will be coming over to the funeral of the Good Friday Agreement, not to the celebration of its 25th anniversary”.

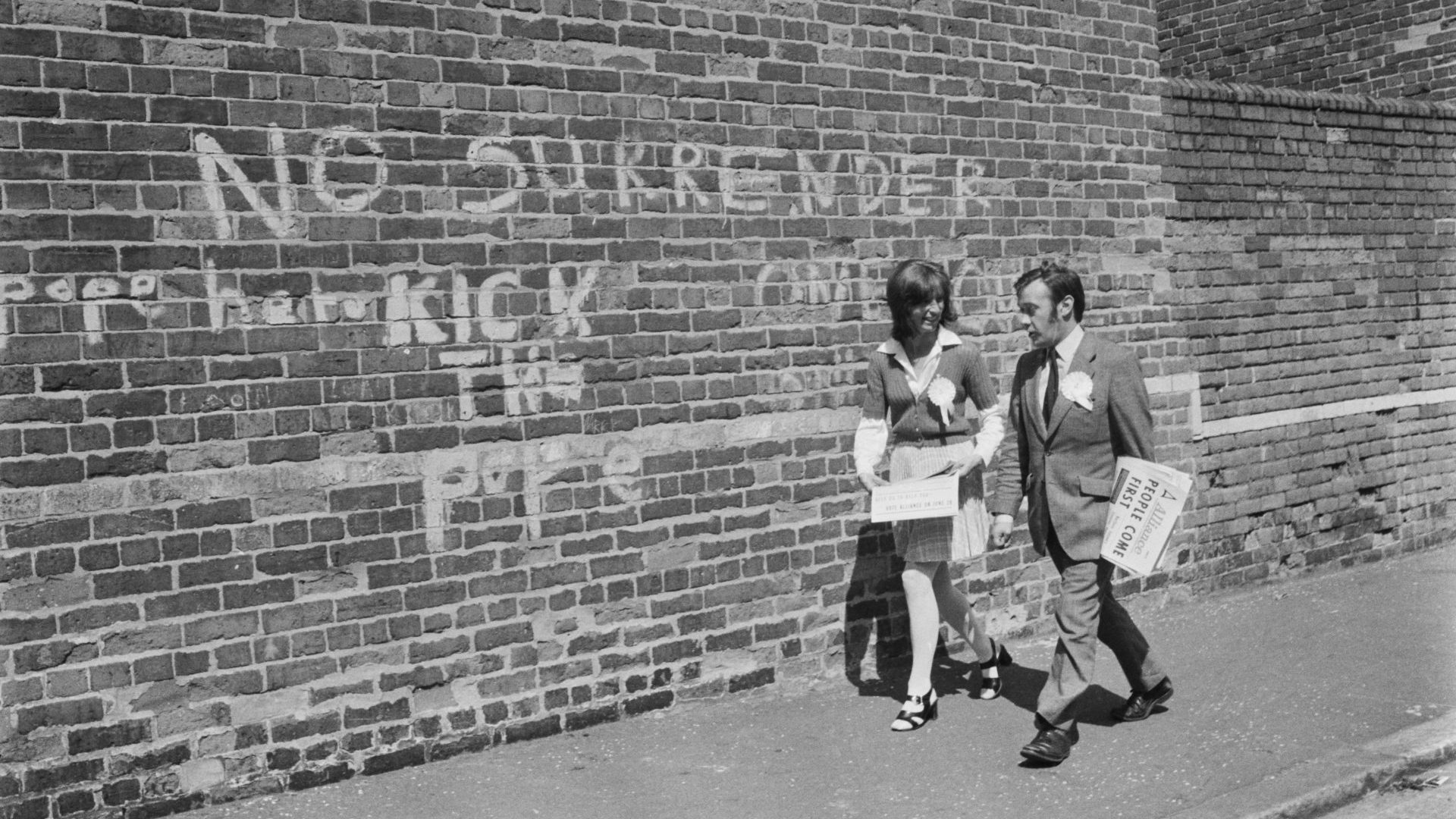

Unfortunate and sometimes hostile choices of words have been the bane of unionist analysis over the years when the prevailing tone should be of neighbourliness and persuasion. There is likely to be a delay in that bill, however, and the result of that is Northern Ireland heading back to the polls. A more pointless ballot would be hard to imagine – as the rest of the UK and Ireland dig in for a winter of Covid, flu and renewed economic hardship, Northern Ireland would have the added diversion of bill posters, flyers and old wounds reopening.

While it is fashionable to think that there is a new confidence in talking about a “united Ireland” – it is not so new in nationalist circles. What is genuinely new is the view expressed in August by O’Neill that there was “no alternative” to the decades-long IRA campaign. This outraged the constitutional nationalist Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) and provoked a sharp riposte from Taoiseach Martin, but 70% of nationalists in a poll by Lucid Talk agreed with her.

It seemed to demonstrate once more Sinn Féin’s alertness to what Irish public opinion is ready to accept. The comment itself is odd. Why would a Sinn Féin leader have to offer such a defensive explanation for violent opposition to British presence in Ireland?

The characterisation of the innocent lives lost, the thousands of life-changing injuries, the decades of distress, anxiety and low-grade sectarian hostility, as somehow unavoidable, seems to have worked its way into the bloodstream of unionism. What was just another Sinn Féin self-justification simply to be dismissed by pacifist nationalism has sunk deep roots into the attitudes of victims, and Protestants generally.

It came at a time when sectarianism appeared to acquire a new respectability. The women’s Irish football team were filmed chanting “Ooh ah up the RA,” in their victorious dressing room after beating Scotland on October 11. Earlier in the year, members of the Orange Order were filmed singing an offensive song about the 2011 murder in Mauritius of Michaela McAreavey, daughter of noted Gaelic football coach Micky Harte, on her honeymoon, an atrocious crime that had united people in Ireland in anger.

Goading songs, abusive terminology, flags and photographs on bonfires – all the old furniture of sectarian tribalism seems back in vogue like flock wallpaper, a tribute to the failure of politics to grasp that the point of the GFA was precisely to build reconciliation between the factions and stifle communal hatred. That was to be the route to agreement and a shared future, not some fictional secret clause that maintained the status quo or implied a united island in 20 or 30 years.

Brexit continues to be a running sore in Northern Ireland, fomenting sectarian division and hardening attitudes. The persistent failure or inability to devise measures and initiatives to build reconciliation remains a serious indictment of the political process in London, Belfast and Dublin. When reconciliation comes to mean dilution or simple compromise, it is doomed.

It is worth noting that the DUP conference began with reflection on the tragedy unfolding that weekend at Creeslough. The unionist people and their politics have much to contribute to the future of the island and the common instinct for compassion is not an insignificant shared contact. But making Northern Ireland a success – as with so much else in life – depends on looking out for one’s neighbours.