It might have been the closest Italy has yet come to its own Brexit moment – a night that divided a nation, left politicians spitting in disbelief and caused delight and disgust on social media. And the cause was a televised song contest.

In February 2019, there were two serious contenders to win the Sanremo Music Festival, the annual five-day televised event that inspired Eurovision and has become an Italian obsession and celebration. One was Ultimo, a young white singer from Rome who had won the contest’s award for up-and-coming talent a year earlier.

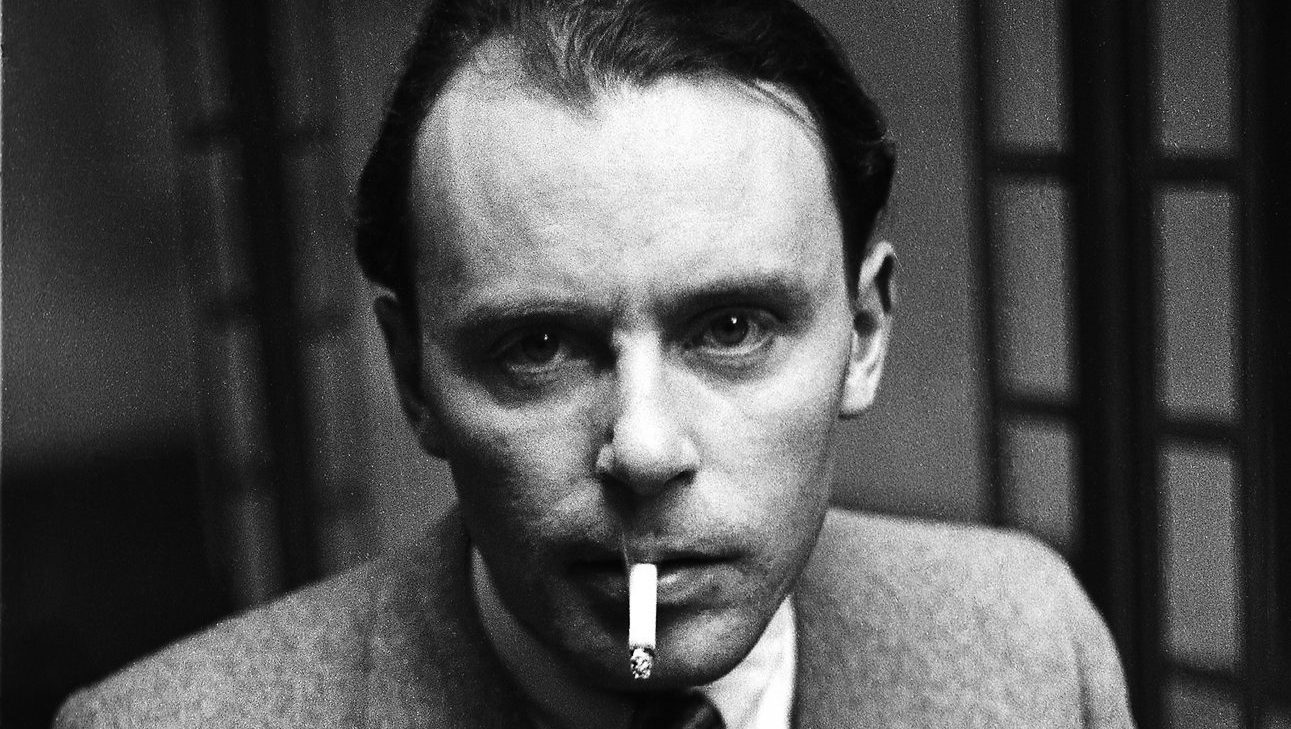

The other was Mahmood, born in Milan to an Italian mother and an Egyptian father. His song Soldi (Money) was sung mostly in Italian, but for one line in Arabic and this, coupled with the singer’s mixed heritage, led to intense criticism from far right politicians such as Matteo Salvini, leader of the Lega Party and now the country’s deputy prime minister.

In the initial public vote, to whittle 24 contestants down to just three, Ultimo won 46.5% and Mahmood only 14.1%. But as with its descendant, Eurovision, the public vote is worth only half of the final total, a jury vote holding equal weight. Both men made it through to the run-off.

In what is dubbed the Superfinal, Ultimo did even better than before, taking 49% of the public vote. The operatic trio Il Volo took 30%, pushing Mahmood into third.

It didn’t matter. When 64% of the jury vote swung behind Mahmood, he was declared the winner. “Here is a mirror of the country,” Salvini declared, “the opposition between people and elites.” The inevitable xenophobic pile-on followed.

If you are struggling to understand how a battle of two songs became an important moment in Italian culture – and the country’s ongoing culture wars – then you need to understand the extent to which the Sanremo Music Festival dominates life in Italy each time it comes around. It has done so virtually since its inception in 1951, and despite a fractured media landscape its popularity may even have grown since the invention of social media.

Last year’s edition of the world’s longest-running annual national TV music competition, and one of the world’s longest-running TV programmes, was the most watched since the turn of the century.

Some 17 million Italians gathered with friends and family in front of their TV sets for the first part of the final, around 70% of the available audience. The second part, broadcast after midnight, was watched by 11 million, 78% of the available audience at that time of night.

Not only is it a barometer of Italian musical tastes, but it is also a barometer of the country’s mores, its contradictions, its changes. It is an arena in which notions of gender and sexuality are debated and defined as well as the fundamental question: what does it mean to be Italian?

When Sanremo kicks off again on February 11, the annual party will be more celebratory than usual. It is the 75th contest, a landmark that would no doubt astonish Amilcare Rambaldi.

A qualified accountant turned flower wholesaler; a second world war hero who was now president of the Ligurian coastal city’s Flower Merchants Association, Rambaldi had been tasked with ideas for revitalising the local economy in the aftermath of the war. His first idea was a film festival, quickly dropped when Cannes relaunched in 1946. His second was a music event.

The first edition was held at the Sanremo Casino and after Rambaldi gained the support of RAI, the state broadcaster, aired live on the radio across the country. In the early years, Il Festival della canzone Italiana, as it is officially known, did exactly what the title suggests; it was the Italian Song Festival; a competition for songs, not artists.

Twenty were performed by three singers and the following year 20 were again performed, this time by five singers. This led to what look today to be bizarre results, the singer Nilla Pizzi coming first and second in 1951 and first, second and third in 1952.

In 1955, the festival made the transition to TV, with the final also broadcast in Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland via the European Broadcasting Union’s Eurovision Network. Members of the EBU’s programme committee, looking for ways to make their co-productions more entertaining, attended the festival in person. They loved what they saw and the following year the Eurovision song contest was launched.

Over the years, many Sanremo winners and competitors have gone on to represent Italy at Eurovision – Mahmood came second in Tel Aviv after his controversial Sanremo win in 2019.

Perhaps the most memorable Eurovision export was Domenico Modugno in 1958. He won Sanremo with Nel Blu Dipinto di Blu, (In the Blue [Sky] Painted Blue) more commonly known simply as Volare (To Fly). Although he only came third at Eurovision, beaten by the now largely forgotten Dors, Mon Amour (Sleep, My Love) by André Claveau, the song was that year’s breakout success.

It embodied a new, lighter style of Italian music, in contrast to the sentimentalism of the past. It also heralded the country’s economic miracle, which saw living standards improve as companies such as Fiat and Olivetti helped Italy to become a global economic power.

With his arms spread wide open as he sang, it was as if Modugno was uniting his fellow Italians, inviting them to soar to new heights with him. Volare was a huge global success, spending five weeks at the top of the US Billboard chart and winning Record of the Year and Song of the Year at the first Grammys.

RAI’s involvement was crucial in ensuring what might otherwise have been just a provincial competition. One of many song festivals across the country became a nationwide sensation, thus embedding Sanremo firmly within the Italian cultural landscape.

“Sanremo is one of the most important popular cultural events in Italy. It is very important for the construction and reproduction of national cultural identity,” says Dr Manuela Caiani of the Scuola Normale Superiore, a leading Tuscan university. “Through music, which includes not only the words but also the performance, Sanremo has been an arena where cultural values and norms of Italian society are negotiated. This includes many political issues: Europe, immigration, gender, the role of the family, the role of women.”

This was apparent even in its earliest years. In 1952, the winning song Vola Colomba, (Fly, Dove) was a nod to the contested city Trieste, stripped from Italy in the aftermath of the war.

The cheerful, even child-like song Papaveri e Papere (Poppies and Ducks), which came second, was a satirical swipe at the ruling Christian Democratic party and the inequalities between rich – the poppies – and the poor– the ducks. In 1984, host Pippo Baudo invited striking steelworkers on to the stage to give a platform for their protest against job cuts.

Some of the controversy that has marked the festival seems inconsequential in retrospect, such as when the 1965 winner Bobby Solo scandalised audiences by wearing black eyeliner. Or when, in 2012, co-host Belén Rodríguez wore a dress slit to the waist and revealing a butterfly tattoo on her inner thigh. The debate as to whether she was wearing any underwear exploded on social media, and has never fully abated.

There have been rows about plagiarism, lip-syncing and jury-rigging, about whether it is sexist to hand flowers only to female contestants after they perform, and whether a #MeToo tribute in 2018 was undermined when the closing credits played out to a lingering close-up of contestant Noemi’s cleavage.

Perhaps the contest’s darkest moment came in 1967. After the controversial folk-pop star Luigi Tenco sang badly in a duet with national treasure Dalida, causing their song to be eliminated, he was found dead in bed with a gunshot wound to the head. An inquest heard that Tenco had been depressed after his poor performance, the result of taking barbiturates with alcohol. Some still insist that he was killed – perhaps in a robbery gone wrong, perhaps because of his relationship with Dalida, perhaps because he was intent on exposing a bribery scandal at the contest.

The hyper-polarised 1970s that followed, a decade punctuated by bombings and kidnappings, saw Sanremo suffer something of a decline. In 1977, the festival moved to a new venue, the Teatro Ariston, where it has remained ever since. It signalled a shift in tone and production values.

“In the 1980s, Sanremo was rebranded a little bit, specifically to become a TV event,” says Dr Enrico Padoan, also of the Scuola Normale Superiore. “Before, it was a song contest that was televised.”

The 1980s and 1990s were the festival’s golden age, and it became more international in scope. Overseas stars had long been part of the festival – for years, the likes of Ray Charles, Cher, Stevie Wonder and Shirley Bassey performed their own versions of the competing songs after they had been sung by Italians. Now, acts like David Bowie, Depeche Mode, the Smiths, Blur, Oasis, Kiss, Bruce Springsteen, and Madonna made guest appearances with their own music, out of competition.

In 2001, complaints about Eminem led to Sanremo’s Public Prosecutor’s Office scrutinising the lyrics of The Real Slim Shady before giving him the go-ahead to perform, which he did without incident. Four years later, Will Smith gave a 20-minute performance during which he “punched” the host, Paolo Bonolis. Unlike “The Slap” at the Oscars in 2021, it was staged.

Despite the emergence of a host of imported homogenised rivals such as The Voice of Italy and The Italian X Factor, Sanremo remains dominant in the country’s popular culture. In the last five years, this has in part been due to the Fantasy Football-style game FantaSanremo, which was created by a group of friends during the first Covid lockdown.

Players form a “team” of five singers taking part, and excitement builds from December when the festival’s line-up is announced. In 2024, there were 2.6 million players and 4.2 million teams across 492,000 leagues.

“I would say that Sanremo is very strong,” says Padoan. “The competition from other reality shows is limited because many winners of those contests end up finding legitimisation at Sanremo.”

Måneskin, who won Eurovision in 2021– Italy’s first success at the competition for more than 30 years – came to prominence when they placed second in the X Factor four years earlier. However, it wasn’t until they won Sanremo that their ascendancy in their home country was confirmed.

In a rebuff to Salvini, the wider public embraced Mahmood after his victory, too. Soldi topped the country’s charts, and in collaboration with Blanco he won Sanremo again in 2022. Though a hat-trick attempt failed when he finished sixth last year, his accompanying album Nei Letti degli Altri (In Other People’s Beds) topped the Italian charts.

Yet with Salvini alongside Giorgia Meloni in power, these are changed times in Italy. Sanremo has responded with a moratorium on political content.

“It’s no longer a macro world,” said Carlo Conti, the host and artistic director, in the build-up to the event. “The songs don’t talk about immigration or war, but return to talking about the micro world, about family, about personal relationships.”

Will the contestants and those in the audience pay heed? We shall see.