The atmosphere in Taipei remained calm, by all accounts, even as the combined might of the Chinese People’s Liberation army, navy and air force had set out to demonstrate that the island of Taiwan’s current self-governing arrangements were doomed. But local reports suggested that apart from a thunderclap on the first day of the military exercises that occasioned momentary alarm, daily life in the Taiwanese capital, and across the country, continued undisturbed.

Chinese missiles flew over the island; the Taiwan Strait was blockaded; Chinese fighter jets intruded into Taiwan’s air space; warships entered Taiwan’s territorial waters. This display of force was broadcast across Chinese state media and was intended as a riposte to Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan – the US Speaker of the House is a long-term critic of China. Many governments, already traumatised by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, held their collective breath, wondering where the confrontation might lead. In China, a population used to nationalist messages mostly cheered, though some netizens complained that not enough blood had been shed.

The situation did not escalate, nor was it a rehearsal for a Chinese invasion of Taiwan – that would have needed many times more manpower. Instead, the sudden flurry of Chinese military activity was a calculated display of might intended to intimidate Taiwan, to probe the island’s defences and to flatter China’s nationalists into thinking that President Xi Jinping’s China could tell the United States where to get off. It was also intended to show that air and sea routes vital to Taiwan’s interests could be shut down at China’s discretion, and to raise the diplomatic and economic risks for governments in the region of appearing to support Taiwan’s continued right to exist.

Pelosi insisted that her trip was intended to support Taiwan, but no policies or agreements were discussed and as her plane took off it was hard to avoid the impression that here was a politician looking to end a long career with a big finale. No Taiwan government can afford to offend the Speaker of the House of Representatives, since it is Congress that approves US military support. President Biden had been uncomfortable with Pelosi’s visit. His military advisers were warning that the trip was ill-timed, as Xi’s current political efforts are focused on ensuring that the upcoming party congress gives him a third term. He cannot afford to show weakness.

Biden’s problem was similar: Donald Trump’s erratic approach to diplomacy did lasting damage to US standing in the region and locked US-China relations into confrontation mode. Trump also pulled out of a huge regional trade pact that Barack Obama had spent years negotiating, insulted key allies like South Korea and accused China of “raping” the United States, which Trump said justified launching a trade war. Biden has left Trump’s trade measures in place while trying to repair some of the wider diplomatic damage, but with the mid-terms approaching, publicly opposing Pelosi’s trip would have made him look soft on China. In the end, the fallout from the visit included China’s cancellation or suspension of a series of bilateral meetings with the US on military contact and coordination, cooperation on narcotics, criminal investigation and, most seriously, climate change.

Beijing insists that Taiwan has always been part of China, but it has also claimed that peaceful reunification was the intention, and that force would be a last resort. In Xi’s ultra-nationalist China, however, where everything is viewed through a lens of strategic rivalry, national security and threats, Taiwan has become a totemic issue, a national wound that must be healed, by force if necessary. It is now central to the restoration of national dignity, which Xi has made the core of his appeal. Like Putin with Ukraine, Xi complains that China cannot feel complete until Taiwan is restored to the motherland. And again, like Putin, Xi’s historical justifications are highly questionable.

How true is the Chinese claim that Taiwan was “always” part of China? Ask that question in Beijing and the answer would be, “absolutely true”. But Chinese official histories serve current political needs and often flatten inconvenient facts into smooth, unchallengeable claims. One especially inconvenient fact is that, for most of history, Taiwan was not part of China at all.

Taiwan’s original inhabitants were from Polynesia, and for most of the island’s history it has lain politically as well as geographically offshore. It was named Ilha Formosa (Beautiful Island) in the 16th century by passing Portuguese, and when the Dutch East India Company established a colony there in the 17th century they encountered no trace of Chinese administration.

The island first came directly into mainland affairs when Manchurian invaders breached the Great Wall in 1644 and stormed into Beijing. The last Ming emperor hanged himself on news of the barbarian invasion, but the Chinese military fought on, before retreating to Taiwan in 1662, incidentally ending the Dutch rule of the island. The island eventually surrendered in 1683, and Taiwan remained part of the Manchu (Qing) empire until 1895, when the emperor ceded the island to Japan, after defeat in the first Sino-Japanese war. It remained a Japanese colony until Japan’s defeat in 1945.

In the 1930s the man who would eventually become China’s supreme leader did not see Taiwan as national territory. When Mao Zedong received the American journalist Edgar Snow in his cave in Yen’an in 1936, and laid out his strategy for a future communist China, he was clear about what was and what was not Chinese territory. Manchuria had been invaded by Japan in 1931 and Mao was clear that it had to be rescued from occupation. However, Korea and Taiwan, both also occupied by Japan, were different: they needed help to overthrow the Japanese colonisers, Mao said, and become independent states.

“If the Koreans wish to break away from the chains of Japanese imperialism, we will extend them our enthusiastic help in their struggle for independence. The same thing applies for Formosa,” he said.

Mao wanted an independent Taiwan. So why does the Chinese Communist party, which still venerates Mao as its founding leader, now want the opposite? In 1945, after the Japanese defeat, Taiwan was handed over to the Chinese government of Chiang Kai-shek. When the communists defeated him in the civil war, his government, along with its surviving army and political followers, fled across the straits. Taiwan became the seat of the nationalist government-in-exile, a harsh dictatorship with pretensions to be the legitimate government of all China.

The US remained a key supporter of its wartime ally Chiang Kai-shek, even though his regime was authoritarian and his party in its early days had enjoyed Stalin’s support. But once the cold war set in, Chiang’s anti-Communism offered the US a chance to showcase the benefits of capitalism to south-east Asia.

Taiwan was then a largely agrarian economy that was struggling to recover from the war. It also had to accommodate nearly two million mainland refugees overnight, equivalent to an extra 25% of the population.

It was also at the mercy of the ever-shifting US-China relationship and when Richard Nixon went to China in 1972, Taiwan entered a new phase of precarious dependency on the US. China had been a founding member of the United Nations and held a permanent seat on the Security Council. In 1971, the General Assembly voted two-thirds in favour of a resolution proposed by Albania, then a close ally of Beijing, to recognise the People’s Republic of China as the only legitimate representative of China to the UN. After a brief procedural battle, Taiwan withdrew. Countries around the world followed the US’s example and shifted diplomatic recognition to China, acknowledging China’s insistence that there was only one China and Taiwan was part of it.

Even so, the US maintained strategic support for Taiwan, pledging military support, as long as Taiwan did not move to a provocative declaration of independence. Mao had intermittently ramped up nationalist feelings about Taiwan for his own domestic political ends, presenting the island’s close relations with the US as evidence of its intention to invade China. Now, though, he made it clear that recovering Taiwan was not a priority. It could wait 100 years if necessary, he said.

Taiwan’s internal politics were also evolving. Chiang Kai-shek died in 1975, a year before Mao. His son and successor, Chiang Ching-kuo, lifted martial law in 1987 and encouraged a democratic shift in Taiwan’s politics. By 1991, the Taiwanese government had abandoned the fantasy that it was the government-in-exile of all China, and a new identity began to emerge — that of a successful, modern democracy, distinct from its giant autocratic neighbour.

With US investment, Taiwan embarked on 30 years of growth, becoming a technological powerhouse. As one of the most successful of the four postwar Asian tigers, it trod a path that others copied, first by manufacturing cheap goods for export, then moving from imitation to innovation, from Made in Taiwan to Made by Taiwan, from T-shirts and toys to television sets, from textiles to computer chips.

When it was China’s turn to enter a phase of rapid growth, Taiwanese businesses poured billions of dollars of investment, along with management expertise and technology, into China. Even after the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989, when western companies paused their activities in China, Taiwan continued to invest. Taiwanese companies such as FoxConn helped China to become a manufacturing powerhouse, turning out iPhones for western markets. By 2020, cross-straits trade was worth US$166bn.

There was, however, a paradox: as China grew richer, its leadership, traumatised by the events of 1989 and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union, took refuge in a new narrative of truculent nationalism, intended to justify its hold on power. In this story, hostile foreigners always sought to undermine China. Taiwan, with its dependence on the US, became central to the heightened nationalism of China’s domestic politics.

By 1995, despite continuing cross-straits investment, China was portraying Taiwan as a wound in the national psyche that must be healed through the sacred mission of unification, and accompanying this with military threats. It became a touchstone issue in the Chinese Communist party’s internal power struggles and that year, national television showed coverage of missile exercises against Taiwan, setting a precedent that would be repeated whenever it suited China’s domestic politics. President Clinton responded by sending a US naval task force through the Taiwan Strait. For the People’s Liberation army (PLA), no longer facing a threat from the USSR and anxious to justify its steadily increasing budget, the occupation of Taiwan became a core mission.

The arrival of Xi Jinping in power in 2012 began a new era of confrontation. Xi believes that the US is in decline and China is in a new era of opportunity. He tells his people that his mission is to restore China to greatness. The recovery of Taiwan is the final piece, the emotional centre of his bid for greatness. China continues to say it wants “peaceful reunification”, but Xi’s brutal suppression of protests in Hong Kong destroyed any remaining faith in the formula of “one country, two systems”. Few in Taiwan would believe Beijing’s promises today.

Taiwan has lived with an intermittently threatening mainland for more than 70 years, and yet has become one of the most successful societies in Asia, a living rebuke to the contention that democracy is a failing idea. Xi will know that a move against Taiwan would be costly and could rouse US regional allies such as Japan and South Korea. The tensions provoked by Pelosi’s visit have created an uncomfortable dilemma for the region, as countries come under pressure from both the US and China to take sides in a fight in which everybody would lose.

In the short term, war seems unlikely, although there is always the temptation of an adventure if the regime feels the need to distract from its domestic problems. More likely is the scenario laid out in a recent interview by the Chinese political scientist Zheng Yongzhen. Prof Zheng argues that US domestic tensions are forcing the US into “salami slicing” tactics to promote independence for Taiwan. The remedy, he argues, is for China to do the same, using salami slicing tactics to promote reunification. “In this sense, getting serious about the military drills is the start of a gradual reunification in the ‘salami slicing’ style,” he says. The recent military drills, he points out, encroached on Taiwan’s maritime and airspace without Taiwan firing a shot and China has declared that the Taiwan Strait, one of the world’s most important shipping channels, is not an international waterway.

“This time,” Zheng said, “we showed the world that the so-called Taiwan Strait median line never existed, because Taiwan never gained independence, so why would there be a median line within the borders of a country?”

The Chinese military has not yet demonstrated that it is capable of invading and occupying Taiwan, but clearly it can blockade the island, at least for a limited time. The difficulties of occupation, however, have been starkly illustrated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and Taiwan has some globally significant assets, such as the world’s most advanced semiconductor manufacturers, which are crucial for China’s economy and military.

If the Taiwan Policy Act 2022, a bipartisan senate bill introduced in June, becomes law, it would significantly increase the US commitment to Taiwan by increasing military aid and designating the island a “major non-Nato ally”. Beijing, in turn, has reaffirmed its determination to secure the island in a newly released White Paper. Anxious about a further round of confrontation with China, the White House is expected to water the bill down.

The recent confrontation, and President Biden’s confusing comments about US intentions, have raised again the question of whether the US would intervene militarily if China were to attack. If Zheng is right in his analysis, that may be the wrong question.

As the much-misquoted Chinese strategist Sun Zi said: “The supreme art of war is to subdue the enemy without fighting.” China managed to militarise and gain effective control of the South China Sea without a direct military confrontation. Invading Taiwan would cause a global shock that would dwarf the Ukraine crisis. Attrition, rather than confrontation, may prove to be China’s game.

Isabel Hilton is a visiting professor at King’s College London

How Taiwan’s bigger neighbours have shaped its fortunes

1683 China’s Qing Dynasty formally annexes Taiwan. It was previously divided between aboriginal kingdoms and Chinese and European settlers, most prominently the Dutch.

1895 China cedes Taiwan, among other territories, to Japan after losing the first Sino-Japanese war.

1935 Japan, ramping up for war, begins to send settlers to Taiwan. By 1938, almost 310,000 have moved to the island nation.

1940 Japan enters the second world war. Tens of thousands of Taiwanese are conscripted into the Japanese army.

1942 China’s Kuomintang government renounces all treaties with Japan and demands the return of Taiwan as part of any postwar settlement. This is endorsed by the allies in the Cairo Declaration in 1943.

1945 After Japan’s surrender, China assumes control of Taiwan. 300,000 Japanese settlers are expelled. Civil war resumes on the Chinese mainland between Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang and Mao Zedong’s Communists.

1947 The postponement of local elections, raging inflation, the seizure of Taiwanese property businesses and the shooting of a protester leads to what is known as the February 28 incident. Massive anti-government protests are suppressed by governor Chen Yi, and between 18,000 and 30,000 people are killed. Martial law is imposed. Thousands of survivors are banned from political activities.

1949 Chiang Kai-shek concedes defeat and evacuates his government to Taiwan, declaring Taipei the new capital of China. Two million Chinese nationalists join him, swelling Taiwan’s population to 8 million. Chinese gold and currency reserves are looted and taken to Taipei. The so-called White Terror begins, with 140,000 suspected communist sympathisers executed or jailed over the next 38 years.

1955 Harry S Truman ramps up US aid to Taiwan as skirmishes continue in the Taiwan Strait. Military fortifications are built up and huge revamps of industry and infrastructure are launched at the dawn of what is called the Taiwan Miracle.

1959 A 19-point package for economic and financial reform cements the Miracle. It liberalises market controls, stimulates exports and allows foreign investment to begin pouring in.

1971 Taiwan loses the UN seat that it’s held since 1946 as the Republic of China to Mao’s People’s Republic. The UN recognises communist China as the country’s sole government after Chiang Kai-shek refuses a dual-representation deal.

1973 The Industrial Technology Research Institute is set up, signalling Taiwan’s determination to move its economic base from industry to innovation. Startups based around computing begin to appear.

2000 Chen Shui-bian wins the presidential elections ending the Kuomintang party’s 50-year rule. He says in his inaugural address that he will not declare independence on the condition that China does not attack. In response, China accuses him of insincerity. claiming that he has evaded the key question of whether he considered Taiwan part of China.

2005 In the latest exhibit of sabre-rattling, China’s parliament passes an anti-section bill authorising the use of force if Taiwan declares independence. Taiwan condemns the new law.

2008 The nationalists are back in power as Ma Ying-jeou, leader of the opposition Kuomintang party, wins the presidential elections. Above, he is met with protests by pro-independence supporters during a visit to the US in 2006.

2014 In a key political step, China and Taiwan hold their first government-to-government talks since the communists came to power in 1949. The Taiwanese government minister who leads the island’s policy towards China travels to the eastern city of Nanjing to meet his counterpart for the discussions.

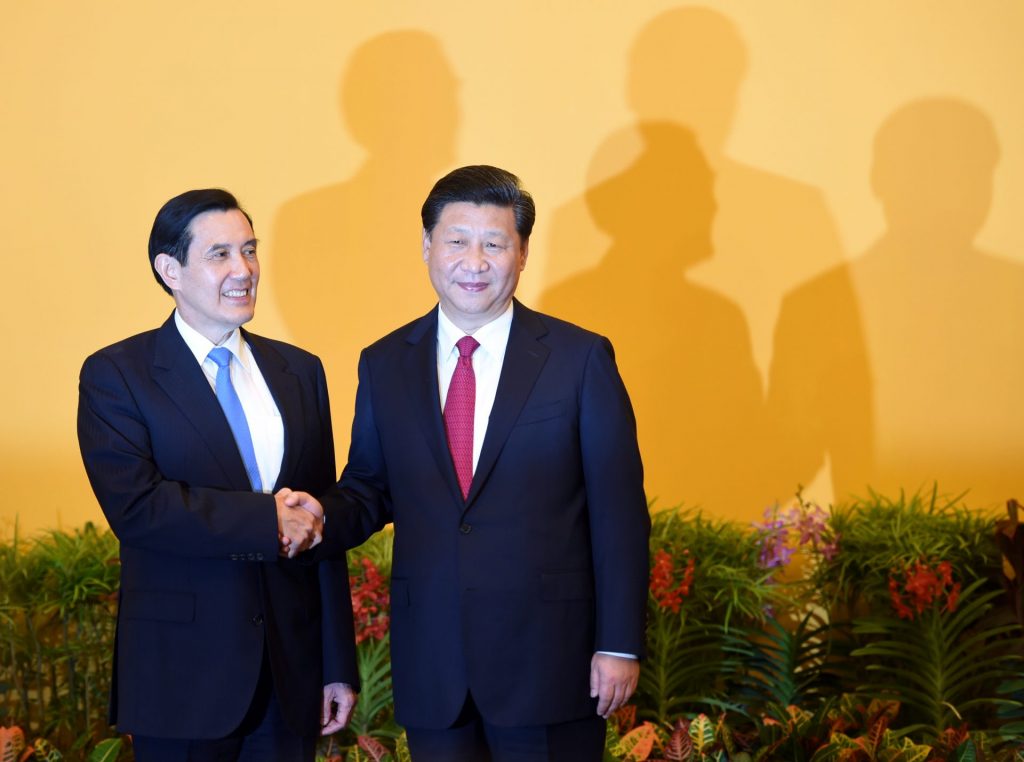

2015 Taiwan’s president, Ma Ying-jeou, and China’s president, Xi Jinping, hold historic talks in Singapore. Again, this is the first such meeting since the Chinese civil war and the nations split in 1949.

2016 Democratic Progressive Party candidate Tsai Ing-wen wins the presidential election, becoming Taiwan’s first woman president

2022 US speaker Nancy Pelosi(pictured above) becomes the most senior politician to visit Taiwan in 25 years, despite warnings from China that Washington will “pay the price for doing so”. In response, Beijing announces military drills in six sea areas surrounding the main island.

Photos: Thomas Cheng/; Rich Schmitt/; History/Universal Images; Roslan Rahman; Chien Chih-Hung/Office of The President/AFP/Getty