It measures 14 feet long by not quite four feet wide. It is yellowed by time and scarred by fire. It has fanned conflict between aristocratic houses, popes, prelates and now scientific and theological researchers.

Google “the Turin Shroud” and you will be offered 2.36m hits in less than half a second. The blogs and theories feature large, but since the 1980s more than 170 peer-reviewed academic papers on the Shroud have been published in scientific and archaeological journals around the world. But despite all this attention, there is little consensus on just how ancient this ancient linen really is, or what it actually shows.

The record places the Shroud in Lirey, northern France, for four years until 1357 and in the alpine town of Chambèry from 1502 to 1578 where it was damaged by fire, before being passed to the Dukes of Savoy. In 1578, the Savoys moved it to their capital, Turin and aside from periods of wartime evacuation, it has stayed in the royal chapel of the San Giovanni Battista Cathedral ever since.

The consensus has been that the Shroud’s history pre-1300 will never be established. And yet the French historian Jean-Christian Petitfils has recently published a seriously reviewed, 400-page analysis of all archaeological and scientific studies so far. And in Italy, the peer-reviewed findings of a specialist X-ray study by a team of physicists indicate that the fabric is potentially up to 2,000 years old. There are now six studies which challenge the idea that the Turin Shroud was nothing more than a cunning piece of mediaeval trickery. Could it be something more?

The cloth, which has been the object of mass veneration by the Catholic faithful for centuries, was acquired by a French knight, Geoffroi de Charny, who deposited it in a monastery in Lirey, about 130 miles east of Paris in 1353. This was a time of unparalleled relic-mongering and forgery and according to the American archaeologist, William Meacham, the shroud most likely arrived in Europe along with many other relics looted from churches and monasteries during the crusades. Research in 2015 reported the analysis and identification of dust and pollen samples extracted by an adhesive which suggested that the Shroud may have undergone a journey from the ancient near east after the sack of Constantinople in 1204.

Still, were it not for the poignant image in its folds, chances are it would have disappeared into the morass of other spurious relics kept in thousands of churches all over western Europe.

In Petitfils’ latest book, Le Saint Suaire de Turin. Témoin de la Passion de Jésus-Christ (The Holy Shroud of Turin. Witness to the Passion of Jesus Christ), he examines more than 100 years of historical, archaeological and scientific research. His conclusion: the cloth “has all the characteristics of authenticity”.

Even those who reject the idea that the shroud is a 2,000 year-old sepulchral cloth, he writes, are unable to explain the imprint of the body. “Adversaries of the authenticity of the shroud come up against an enigma – that this one cannot be the work of a counterfeiter, because to ‘make’ such an image would have required unknown scientific knowledge in the Middle Ages,” Petitfils told Le Figaro. “The image is not a painting. No trace of brush strokes, no outline has been observed even under an electron microscope. We must also exclude the hypothesis of a smear, the application of a bas-relief of wood or marble or a metal statue heated and placed on the cloth.”

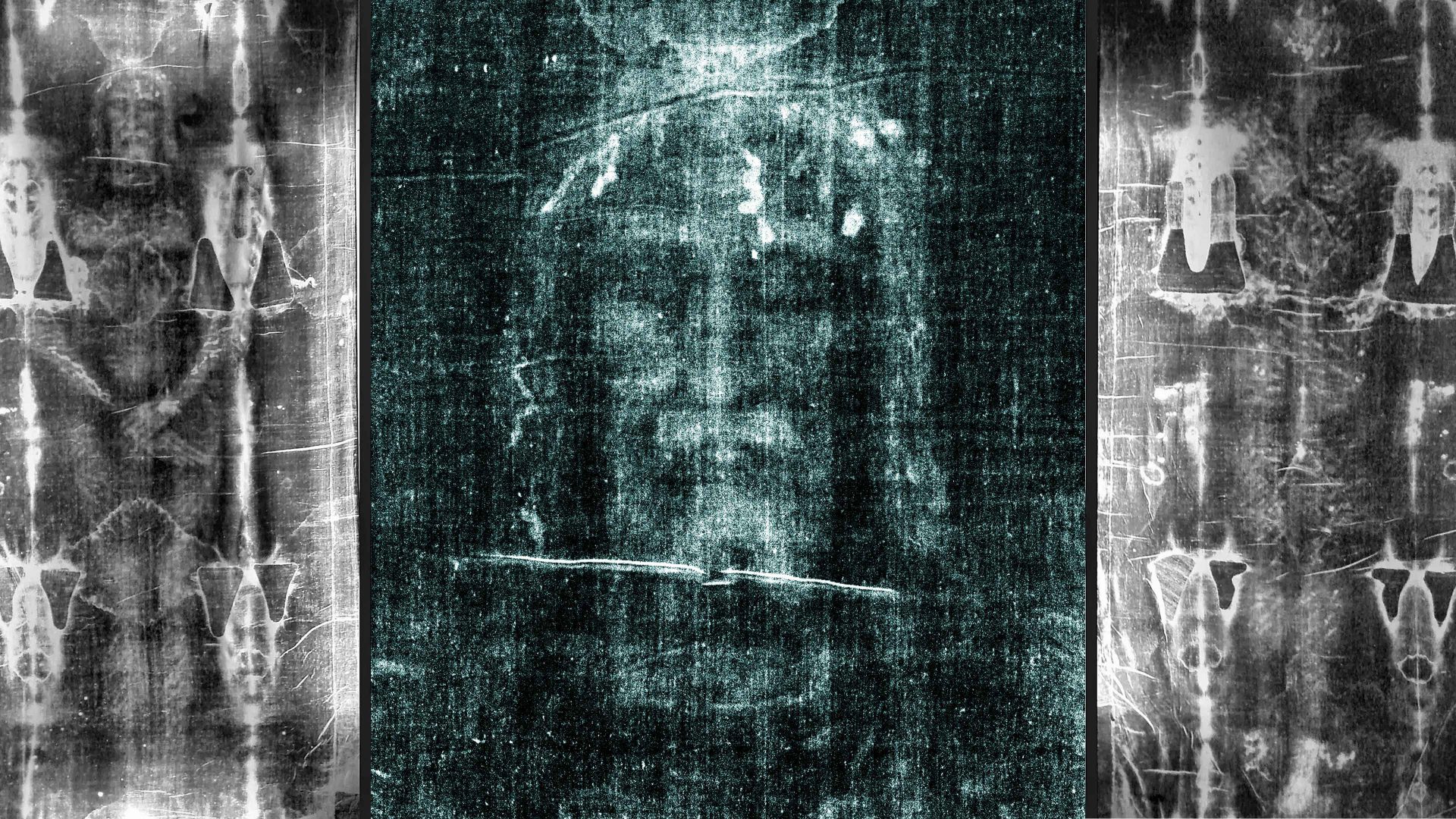

It was the Catholic Church itself that unwittingly sparked what would become a global obsession with the Shroud in 1898 when it gave the green light to a rare public exhibition of the cloth. Secondo Pia, an amateur, became the first to photograph the linen’s strange, sepia shadows and the high contrast created by black and white photography enhanced the blurry stains. When Pia went to the darkroom to check his plates, he was startled to see that the negatives revealed a haunting, perfectly proportioned facial image of a serene, bearded man and the imprint of a body tortured by what appeared to be flogging lacerations and puncture wounds.

The discovery sparked a media storm, and the competing claims of a religious miracle and a photographic hoax quickly piqued global interest. The quest for a serious answer began almost immediately: in 1900, a team at the Sorbonne led by Yves Delage, a Professor of Anatomy, examined the apparent body image and described it as “flawless”, right down to the fine detail, which included signs of rigor mortis. They concluded that the linen had come into contact with a corpse.

The Shroud was next exhibited in 1931, and at that time a new series of vastly more sophisticated photographs was produced, yielding more images and information for scientific scrutiny. However, it wasn’t until 1969 when the Catholic Church sought scientific advice on preservation techniques that access was first granted to the cloth itself.

In 1978, a multi-disciplinary scientific group known as the Shroud of Turin Research Project (STURP) was created and a team of 33 American and European scientists spent five 24-hour shifts studying the linen first-hand. Their report, published in 1981, concluded the image was of a scourged, crucified man, that blood stains revealed haemoglobin and tested positive for serum albumin and that these were “not the product of an artist”.

“We can conclude for now that the Shroud image… is an ongoing mystery and until further chemical studies are made, perhaps by this group of scientists, or perhaps by some scientists in the future, the problem remains unsolved,” the report concluded.

Over the next 40 or so years, a further army of chemists, physicists, forensic pathologists and botanists have examined not just the images but physical samples of its unique twill weave, analysed minuscule leftover fibres and identified further pollens and soils vacuumed from the textile samples and trapped onto sticky slides.

To date, possibly the best known and still the most quoted of these studies was a Radiocarbon 14 dating of postage stamp-sized pieces of the fabric, conducted in 1988 by the Universities of Oxford, Arizona and the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology. This placed the Shroud’s creation somewhere between 1260 and 1390. The authors described it categorically – unusual for scientists – as a medieval fake.

Several subsequent analyses, predominantly led by Italian scientists, have seriously queried these findings. One objection was that the sample fabric came from peripheral later repairs, while others have questioned anomalies in the original study’s reporting methods and the continued failure to provide raw data for re-evaluation.

Petitfils cites the work of a team of Italian physicists who showed that the image is the result of a light, brownish degradation of the linen, but that this discolouration is restricted to the very top of the fibres and at a minuscule thickness of between 20 to 40 microns – thinner than a human hair. This effect would be impossible with paints or pigments. To date, no consensus has been reached on the Shroud’s age, let alone how the image and stains were imprinted – or painted – on the cloth.

Even for a sceptic, there is something strangely moving – and horrifyingly grim – about reading the modern analysis of the body imprint which – some scholars suggest – offers impossibly accurate and graphic detail of the agonising physiological process of dying while hanging by the arms.

Medical papers describe a cadaver, laid out naked, with long hair to the shoulders drawn back into a ponytail. Between 5 feet 9 inches and five feet 11 inches tall, the man weighed around 75 to 81 kg and was seemingly well-proportioned and muscular with no visible defects. Death had occurred several hours before the body was placed onto one half-length of the Shroud, with the other half then drawn up and over the head to cover the rest of the body. The stiffness of the extremities and retraction of thumbs and distension of the feet are signs of rigor mortis. The cloth had been in contact with the body for a few hours – but no more than two or three days.

Gaze at any number of sculptural depictions of Christ and he is often shown big in the chest, the gut strangely concave. Crucifixion by nailing forces the agonised victim to hold in their breath. This leads the rib cage to expand abnormally, making the ribs appear enlarged and drawn upward to the collarbone and arms.

In the lower body, the abdomen becomes distended, while the hollow at the top of the centre of the chest is drawn sharply in. The pain of a slow death when nailed by the wrists and ankles is also shown in the ballooning of hip muscles and the femoral quadriceps, which need to push out in the terrible exertion needed by the victim to haul himself upward by the legs in order to exhale.

Theories on the final cause of death based on the wartime analysis of cadavers, suggest asphyxiation due to muscular spasm, progressive rigidity and the inability to exhale. Another possibility is circulatory failure from lowering of blood pressure and the pooling of blood in the lower extremities.

The ghastly detail seemingly embedded in the Shroud’s image fits Catholic and medieval artists’ depiction of Christ’s suffering. Since ancient times, artists have been fascinated by the workings of the body: sculptors have used marble for centuries to delineate veins and musculature. Leonardo studied cadavers for his anatomical drawings. Perhaps there was a medieval artist so clever and so obsessed with Christ’s suffering that he tried to reproduce his sepulchral cloth, complete with bodily evidence of his agonies?

And even if we cannot reproduce how it was done then, who is to say that it was impossible? Anyone fortunate enough to gaze on the mind-boggling physiological detail sculpted on the Veiled Christ in the San Severo Chapel in Naples, just as one example, could be excused for believing in supernatural artistic forces.

Last year a team led by Professor Liberato De Caro, a physicist with the Italian National Research Council at the University of Bari, published a report on the degradation of the Shroud’s fibres. He used X-rays to determine the effect of time, heat and humidity on the polymer chains of cellulose within the linen.

In an interview with The New European, De Caro said his team has been examining all kinds of linen fabrics at the “scale of atoms” for three decades, using an X-ray scattering technique to pinpoint the age of textiles.

Macroscopic samples of a fabric’s microfiber, he says, look a little like a bundle of spaghetti which appear to all be of the same length to the naked eye. But when subjected to stress or shocks, over time, they break and become shorter.

Natural ageing over the centuries is the result of the combined effects of temperature, humidity, light and chemical agents in the environment. Professor De Caro says his team developed a method to measure natural ageing of flax cellulose in the linen using X-rays and then converting this data to calculate the time elapsed since it was loomed. The method was first tested on linen samples which had already been dated using other techniques, and then finally applied on a sample of the Shroud. Research began in 2019 but was delayed by the pandemic and results were not published until last year, in the academic journal Heritage as well as the website of Italy’s National Research Council.

“X-ray dating does not destroy the sample so the measurements can be repeated many times. Conversely, Carbon-14 dating destroys the sample and so measurements cannot be repeated. We had already performed a blind experiment of X-ray dating on a sample of unknown age,” he told me. “The a priori knowledge was only the geographic locality from where it came but through X-ray dating, we determined the age, which was about nine centuries old. These experimental tests confirmed the reliability of X-ray dating.”

But not everyone is so sure. Mohamed Dallel, a French research engineer specialising in textiles read the Italian study and was unconvinced. Dallel argues that all the factors that degrade textiles are almost impossible to integrate into the mathematical modelling used by the X-ray scattering technique.

Work completed in 2020 by the National Institute of Nuclear Physics in Florence which took samples of wood from another of Christianity’s most venerated relics, the Volto Santo in the northern Italian town of Lucca which concluded, unexpectedly, that it is much, much older than previously thought.

Pilgrims have travelled to the pretty Tuscan town for centuries to worship before the eight-foot-tall wooden sculpture depicting a crucified man, crowned and dressed in a gold tunic, with downcast, gentle eyes. According to legend, the relic was carved by Nicodemus, who helped prepare Jesus for burial.

Yet scholars have been sceptical of that idea. Art historians have pointed to similarities between the style of the sculpture and works by a 12th-century northern Italian artist, theorising that Volto Santo is a copy of a lost 8th-century original.

Three years ago, however, science threw out a rather different but equally extraordinary story – placing the sculpture’s age between the end of the seventh century and the middle of the ninth. According to the mass spectrometry laboratory in Florence, it is Europe’s oldest wooden carving.

Stefano Martinelli, an art historian and expert on the icon says the Volto Santo, mentioned by Dante in The Inferno, is seen by believers as one of the true icons of Christ, comparable to the Turin Shroud, in that devotees believe it was carved directly in his image.

The origins of the majority of religious relics like the Shroud and Volto Santo are rooted in legend. And yet there is often a crossover into recorded history at the point of the Crusades and the large-scale removal of religious artefacts from Jerusalem.

St Helena, mother of the first Christian Emperor Constantine, is said to have been the first, and most important historical figure to visit Jerusalem, with the prime goal of collecting as many relics as she could possibly transport back to Constantinople. It is St Helena who is also said to have discovered the cave in which three crosses and burial cloths still lay and, unsure of which one might have been the one Jesus died on, decided to conduct her own tests by asking sick friends to lie down on each one asking how they felt afterwards. The disappearance of their symptoms told St Helena she had the “real” cross.

Similar tales are woven into the acquisition stories of many other relics important to Christendom, including Jesus’ burial clothes, and for centuries these religious objects were associated more with Constantinople than Jerusalem. In 1204 however, Constantinople, the de facto capital of the Eastern Roman Empire, became the target and culmination of the Fourth Crusade when armies systematically captured, looted or destroyed what was then the world’s largest Christian city, tearing apart relations between the Catholic and Orthodox churches. In 2004, at a distance of eight centuries, Pope John Paul II expressed sorrow and apologised for the way Latin Christians and “brothers in the faith” had turned on their Orthodox co-religionists, asking, “how can we not share the pain and disgust?”

The Turin Shroud occupies a strange space, at the point where legend, history, faith and science all meet. Whether the image is of Jesus Christ, a work of religious, medieval art or the burial cloth of another agonised mortal, it remains one of the most famous objects in the world – and yet it is fundamentally unknowable.

Three relics – are they related?

The Sudarium of Ovi

Held in the Cathedral of Oviedo in north west Spain, this smaller cloth (sudarium means sweat cloth in Latin) is stained with blood and measures 84 cm by 53 cm. It has a written history extending back to approximately 570 AD but was radiocarbon dated to around 700 AD. For many years, researchers have tried to link the sudarium with the Turin Shroud, using its radiocarbon dating to argue likely authenticity. Studies have suggested that matching blood stains and traces of limestone dust suggest the cloths were wrapped around the same person.

Tunic of Argenteuil

This bloodstained and torn woollen textile without seams is kept in the Basilica of St Denis in Argenteuil, in northwestern Paris. It is purported to be the “seamless tunic” referred to in the Gospel of John and for which the Romans cast lots at the Crucifixion. Vague references to the relic have been found in fifth- and sixth-century writings, while in 814, the emperor Charlemagne bequeathed it to the Benedictine convent in Argenteuil where his daughter, Theodrada was Abbess. Walled up with letters in French and Latin attesting to its origin, it survived a Norman invasion that destroyed the convent and was rediscovered in 1156.

Cut into pieces and hidden in different places to survive the French Revolution, it has since been sewn together with a reinforced lining. Researchers since the 1990s have examined the blood stains, found traces of pollen grains common to the Shroud and Sudarium and carbon-dated it to between AD 530-650 and AD 670-880.

Turin Shroud

Believers argue that if radiocarbon datings of the Shroud, to AD 1260-1390; AD 700 for the Sudarium of Oviedo and AD 530-880 for the Tunic of Argenteuil are accurate, this suggests that artists in the Middle Ages produced the relics over many centuries but somehow managed to make sure each contained the same pollen grains, blood types and wound configuration.