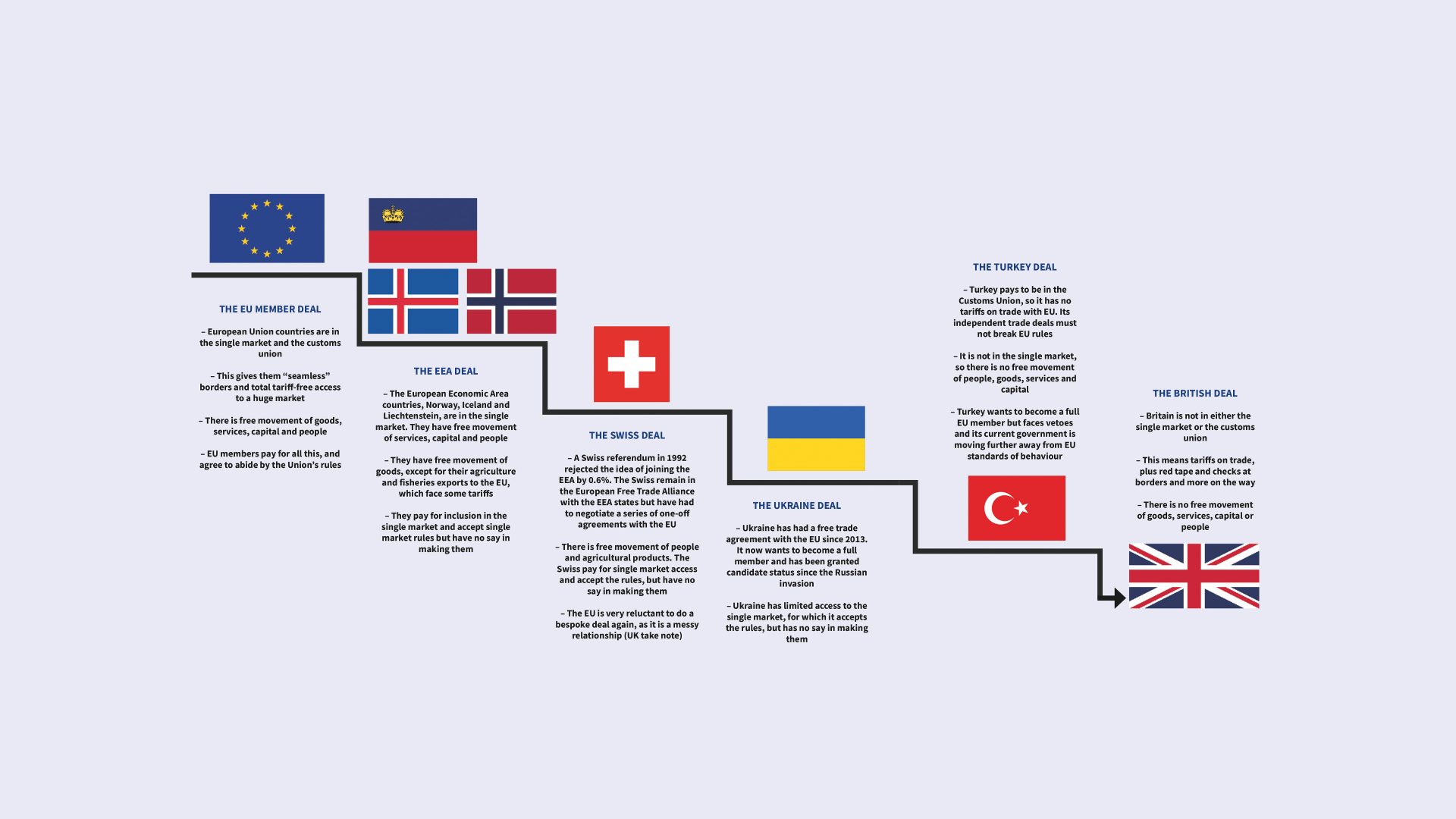

Something is stirring. In recent days, senior Tories from both ends of the spectrum on Europe have suggested things might be simpler and better if Britain were to be back inside, or have closer access to, the EU’s single market. As the economic news gets worse, and it becomes even clearer that the UK’s suffering is greater than that of our neighbours and former colleagues, more voices will surely be added to the clamour for a better way of dealing with Europe.

A better way, perhaps, like Norway’s way. Being in the EEA (the European Economic Area) along with Iceland and Liechtenstein gives it better access to the single market – fewer tariffs, less red tape. Norway has the advantage of cutting its own trade deals and pays only to take part in the bits of the EU it feels it has to join for its own benefit, including the joint criminal intelligence agency Europol and the programme to help students study in other countries, Erasmus+.

Does that sound better than the version of Brexit Boris Johnson has saddled us with? Dr Ulf Sverdrup, director of the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs, does not mince his words. “The pain of the process for the UK has been just spectacular,” he says.

I interviewed Dr Sverdrup in Oslo for a BBC documentary six years ago, before the referendum that changed everything. I spoke to Norwegian firms that had been caught out by new EU regulations, economists, politicians, the fishing industry, farmers and the local equivalent of the CBI.

My conclusion, supported by nearly everyone I spoke to, was that while the system worked for Norway, it would not work for Britain. With a small economy dominated by oil and gas, the Norwegians could easily afford to just follow EU rules and directives to keep trade flowing smoothly and easily in what used to be called “government by fax”. Britain, meanwhile, a huge economy without those reserves of oil and gas, no sovereign wealth fund and large sectors of the economy dependent on trade with the EU, would need a seat at the table when new rules and regulations were discussed, proposed and introduced.

The documentary immediately led to a torrent of online abuse. All of it from Brexiteers. The nicest one was “Why are you such a lying shit, you lying shit?” (and actually, I have cleaned that up a bit). The pro-Brexit mob sent abuse because for them back then, Norway was the perfect solution, what Brexit was all about and the best option for the UK.

Yet the day after the referendum, the Norway option became treason. It was BRINO (Brexit in name only), a betrayal of the vote, it would leave us as a slave state, shackled to a corpse. In the end, the UK was lucky to leave with any kind of deal at all, as the ultras hung on for World Trade Organization (WTO) terms.

Now, six years later, Norway is back on the menu. The ultras are a smaller and smaller group, still powerful, but all that economic damage comes at a price. Moderate Brexiteers can back down and claim Norway was what they wanted all along; many Remainers might be able to live with it and economically it removes dozens of the problems Brexit has caused.

But what would it mean for the UK?

For a start, Norway as a member of the single market adheres to the four freedoms. The free movement of people, capital, goods and services, the very things that the UK is missing Is Norway the way back? desperately. But, unfortunately, the things above all else that the Brexit supporters wanted to end, especially the free movement of people.

It also means that Norway has to accept the rules of the single market, except for those affecting agricultural and fish products, which it fiercely defends, and although it is consulted on any new rules and regulations, it most certainly does not get a vote on any of them.

That means following all the rules on product design and safety, the chemical industry regulations, the CE mark and thousands of others. For much of British industry, this would be a welcome cost saving, and far better than the current mess. For Brexit supporters who thought the whole point of leaving was to shred these rules and make the UK “Singapore-onThames”, it would be unacceptable.

Norway also sends considerable amounts of money to the EU. Some of it so it can take part in specific EU-run and financed schemes, some of it in the form of so-called Norway grants, which fund schemes to promote democracy and reduce economic disparities in the EU.

Not being in the customs union, Norway also has the advantage of being able to cut its own trade deals, although it does this through the European Free Trade Association (Efta). But that does come at a price: Norway’s products, excluding food, enter the EU tariff-free but only if the Norwegian exporters can prove they originated in Norway, so there are checks at the border – just fewer than at the EU/UK border.

Norway and the other Efta members also follow the EU’s SPS rules, which govern food and agricultural standards. The UK opted out of this, which is a huge headache for food exporters, as it means the EU will insist on checks at the border to make sure all food and agricultural products meet its standards. Pretty much everyone but the British government thinks this is stupid, but it seems unlikely to change its mind.

So, the Norwegian option still has all of the problems that I identified in 2016. Professor Erik Oddvar Eriksen is a former head of Arena, the European Studies Centre at Oslo University. As he explains, the EEA option comes down to three simple things: “You obey, you pay, you have no say”. It is that simple.

Not only that, but it is pretty clear that EEA members don’t want the UK to join. As Eriksen put it: “It was a relief when Boris Johnson came down in favour of a harder Brexit.” That was because the EEA countries could easily see what it would be like with the UK in the room, spoiling their nice, cosy deal by arguing over every point.

This attitude was bad enough in a huge club like the EU, but imagine Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein being cajoled by Brexit Britain. Because as Professor Chris Lord of the European Studies Centre and a visiting professor at the College of Europe in Belgium explains, the rules of the EEA mean that it “has to agree together to implement any single market measure”. The UK would, therefore, have the power to veto, ban and block any changes at any time – a step that would allow the EU to suspend the EEA agreement. It would, as the professor says, mean “the EEA would probably collapse if the UK joined”.

When I reported from Norway, my conclusion was that the Norway option would not be best for the UK, but that was in comparison with staying in the EU. Compared with the complete dog’s dinner of a deal the country has now, Norway looks more attractive, although far from perfect. But it still wouldn’t work.

The facts are that the Brexiteers were lying all along. Norway was never an option they would or could accept. Although it would remove many of the barriers to trade with the EU, they would never have accepted having to take all the rules and yet have no say on what the rules were; this is, after all, why they wanted to leave in the first place. And in the EEA the UK would end up taking rules and regulations from Brussels all the time.

And finally, and perhaps most importantly, none of the EEA’s members want the UK to join any more than the EU wants the UK back. Not to put too fine a point on it, no one likes us, trusts us or wants us to be part of their club.

As Chris Lord told me, before we can rejoin any type of closer EU agreement “the UK has to serve its time in purgatory”. And before we even start down that road, there is one huge obstacle that has to be removed. As Dr Sverdrup put it: “As long as friction is there), you cannot build trustful cooperation. Maybe you need another prime minister.”