Nurses and children jumping on beds; umbrella-holding Mary Poppinses rising to the skies; Kenneth Branagh as Isambard Kingdom Brunel, reciting William Blake’s Jerusalem; the chimneys of the industrial revolution’s Satanic mills; Pearly Queens and Mr Bean, who (sort of) plays the Chariots of Fire theme with the London Symphony Orchestra; Voldemort and Harry Potter; and – the piece de resistance – the actual Queen and James Bond in a sketch that would make us believe she jumped from a helicopter while wearing a frilly pink dress.

It’s been a decade since the London 2012 Olympics opening ceremony, but it seems a lot longer. Ten years since the ceremony, directed by Danny Boyle, surprised, delighted and stirred at least a thread of patriotism even in the most cynical; defying predictions that the whole thing would be an expensive cock-up. Involving hundreds of volunteers, the depiction of the National Health Service, imagery of the anti-nuclear CND and the Windrush arrivals from the West Indies, the celebration of both Britain’s finest and ordinary people showed a nation apparently at ease with itself, able to feel pride in its accomplishments but also poke fun at its past. While mining Britain’s culture and history, Boyle had managed to tell a fresh story of a diverse, multicultural, modern nation.

This was a complete departure from the terrifying, regimented grandeur of the Beijing Olympics four years earlier and set the stage for a happy few weeks as Team GB stormed up the medal tables and Mo Farah, Jessica Ennis and Greg Rutherford all won gold on Super Saturday. The infectious good mood lasted all the way through to the previously under-the-radar Paralympics, which with their slogan “Meet the Superhumans”, was a hit like never before.

The ceremony was a hit at home – where 27million watched on TV, a stunning achievement in a multi-channel age – and abroad. German newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung praised its “heart and humour… spectacular but also thoughtful and touching.” Across the Atlantic, the New York Times said it showed Britain as “a nation secure in its own post-empire identity, whatever that actually is.”

These sentiments, together with the optimism of the time, have not aged well. Just think of the change in the national mood between the time the Queen jumped with Bond and earlier this summer, when she took tea with Paddington Bear to celebrate her platinum jubilee.

It is a transformation recognized this week by the Reverend Richard Coles, who tweeted: “Ten years since London 2012. I remember watching the opening ceremony and thinking ;we’ve cracked it — progressive, inclusive, outward looking, and everyone’s cheering’. It’s the most wrong I’ve been since predicting in 1987 that London house prices could not rise any higher.”

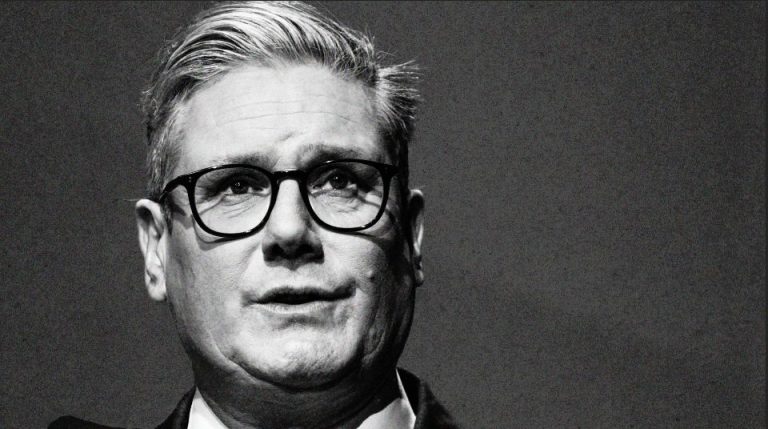

During those ten years, it has become clear that London 2012 wasn’t a new start, but an ending. Britain has descended into a Brexit-induced trauma of division and strife, the chaotic governments of Theresa May and Boris Johnson engendering thin-skinned, aggressive and defensive behaviour. Instead of diversity and multiculturalism, the currency today is of jingoism, nativism, deliberately stoked culture wars and a facile miscasting of history. The failures during Covid and the permanent state of flux for the Union compound the misery.

The Guardian called the 2012 opening ceremony a requiem. But maybe it was more of a mirage. Many will remember the London Olympics fondly, but an undercurrent of political and social life at the time painted a darker picture.

The country was still reeling from the financial crash in 2008, and less than a year before the Olympics began, that same London where the people cheered on Boyle’s Isles of Wonder ceremony was the stage for the biggest riots in modern English history, when violence and looting followed the killing of 29-year-old black father of four Mark Duggan by the police. Five people died and more than 3,000 were arrested in the five days of multi-city rioting that many agreed was “a long time coming” because of the growing inequality and the frustration of young people in the poorer London boroughs. In the same year, two top footballers sparked a scandal by shouting racist taunts at opponents – racism and xenophobia had gone nowhere.

By the time the Olympics began, the Conservative-led coalition that presided over them had begun their austerity programme, which imposed painful cuts to public services. Chancellor George Osborne was booed at the Olympic Stadium. According to a later report on the impact of austerity on human rights by Philip Alston, the United Nations rapporteur on extreme poverty, government policies since 2010, including the introduction of universal credit, had resulted in the “systematic immiseration of a significant part of the British population” and warned Brexit would make this worse. He compared the government’s welfare policies to 19th-century workhouses and maintained that unless austerity came to an end the poorest in the country faced lives that were “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” Welfare, schools, early years care, health and local council services were all affected by the austerity that was firmly in place by the time the 2012 Olympics came around.

The NHS, celebrated with such affection in the stadium, was already hit by austerity belt-tightening despite ever growing demand. Since then it has only got worse, and the early pandemic images of broken nurses sweating inside home-made PPE equipment as they struggled to deal with Covid patients does not tell the story of an institution that is loved and nurtured. Even the soft-focus Olympic depiction seemed to upset Conservative MPs, and not just Aidan Burley, the Cannock Chase MP who called the show “leftie, multicultural crap”, but also culture secretary and future health secretary Jeremy Hunt, who, Boyle later revealed, had wanted the NHS section cut.

The Windrush generation, celebrated in the show, were soon at the centre of a scandal in which many original arrivals and their relatives were unfairly deported because of poor paperwork. Yet the rot didn’t start with the Conservatives – the deportations had also been taking place under Labour well before Theresa May’s “hostile environment” policy in the Home Office was introduced and made everything so much worse.

In May 2012, while volunteers were busy training for Boyle’s spectacular, May had already raised the concept of “hostile environment”. With the support of Cameron, she decided to make “illegal” immigrants’ lives as difficult as possible to help meet her unrealistic and impossible to implement net migration targets – a policy embraced and enhanced by her hardline successor Priti Patel. But again, hostility to refugees, which reached new peaks after the 2015 migrant crisis and led to the current absurdity of deporting asylum seekers to Rwanda, already existed. In the 1990s it was the Labour government that was praised in the media for any hardline statements on refugees.

The Olympic year was a time when seeds of subsequent horrors were being sown. It was in 2012 that some of those new MPs who were to become leading lights in Boris Johnson’s law-breaking, divisive governments – including Dominic Raab, Priti Patel, Kwasi Kwarteng and Liz Truss, set out their “new right-wing” stall in the widely panned Britannia Unchained, a book that famously declared British workers the laziest in the world and advocated red-tape-slashing, low-regulation policies inspired by edge-of-legality entrepreneurism, workers with uncertain, long-hours and brain-crushing educational cramming.

A comment from Truss in 2019, suggesting that the 2012 opening ceremony fits into that vision, shows how pliable the mythology has become: “We need to revive the Olympic 2012 spirit – a modern, patriotic, enterprising vision of Britain and we need to use Brexit to achieve that.”

As the games approached, Nigel Farage was becoming a mainstream figure and worrying Conservatives afraid of losing their right-wing voters to him. In 2012, the word Brexit was invented and barely six months after the Games made everyone feel warm and fuzzy inside Cameron announced that he was prepared to hold a referendum on EU membership, launching a period of social division and leaving the union in a constant state of flux ever since.

The London Olympics should also be remembered for giving one of the defining figures of the era a stage on which to shine. As the newish London mayor, Boris Johnson basked in the glory of the Games, famously dangling from a zipwire waving flags, hijacking Britain’s first gold medal win and burnishing his image as a jovial, fun figure. Many enjoyed the performance. A pity they had not instead watched his performance at the Beijing handover ceremony four years before, where he took the Olympic flag with typically dishevelled hair and clothes, oozing slapdashery.

Does the fact that its daring papered over existing cracks that have since become chasms, or that its promise of a modern, self-deprecating, united Britain has been exposed as a hollow fantasy, mean we should not feel proud of and nostalgic for the 2012 opening ceremony? Does it mean, as the writer Owen Jones has claimed, that those who believe it represented a high water mark for the country are all deluded? “This faction think Britain was a utopian wonderland at the time. It wasn’t,” he complained on Twitter recently.

It is surely too harsh to say those who enjoyed and still enjoy the opening ceremony did and do so while completely oblivious to the nation’s problems at the time. Some people just like The Queen and James Bond. Surely too it is wrong to seek to discredit it because of what went before and what followed. How much does an Olympic ceremony really reflect reality anyway, and how much does it simply reflect how a country wishes to be seen?

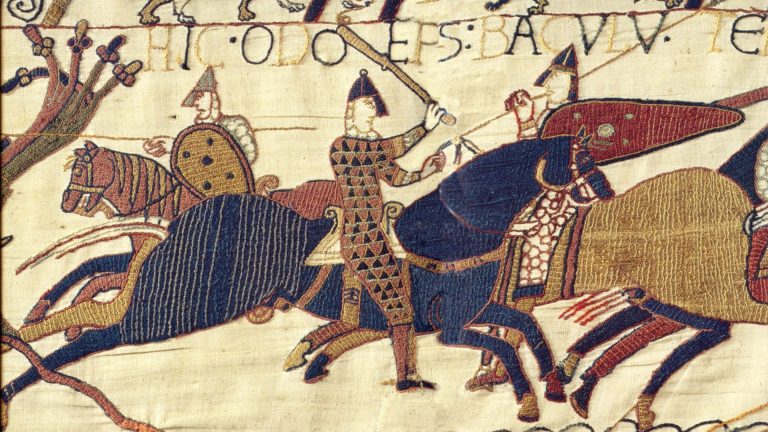

Beijing’s was bombastic and precisely tooled, showing the military, classical musicians and a disciplined people beating drums for national glory – as all the while dissidents were being detained and citizens were terrified of displeasing the government. Rio 2016’s ceremony was a big, raucous, carefree party, held as the country was suffering under social unrest and such economic strain that the Paralympics nearly didn’t happen. In 2004, Athens conjured up the glorious past of the ancient Greeks and the mythology of gods and goddesses as, in the present, the country was rushing headlong into economic collapse. Quirky and irreverent with its history, London showed the melding of the modern and inclusive with the traditional. That was also a story – the reality may never have been like that.

The story of Isles of Wonder contained a dream, a wish, an aspiration for what the country could be. As inequality and vicious political polarisation rips the country apart, it’s hard to see how anyone can even harbour the aspiration of such a vision today.