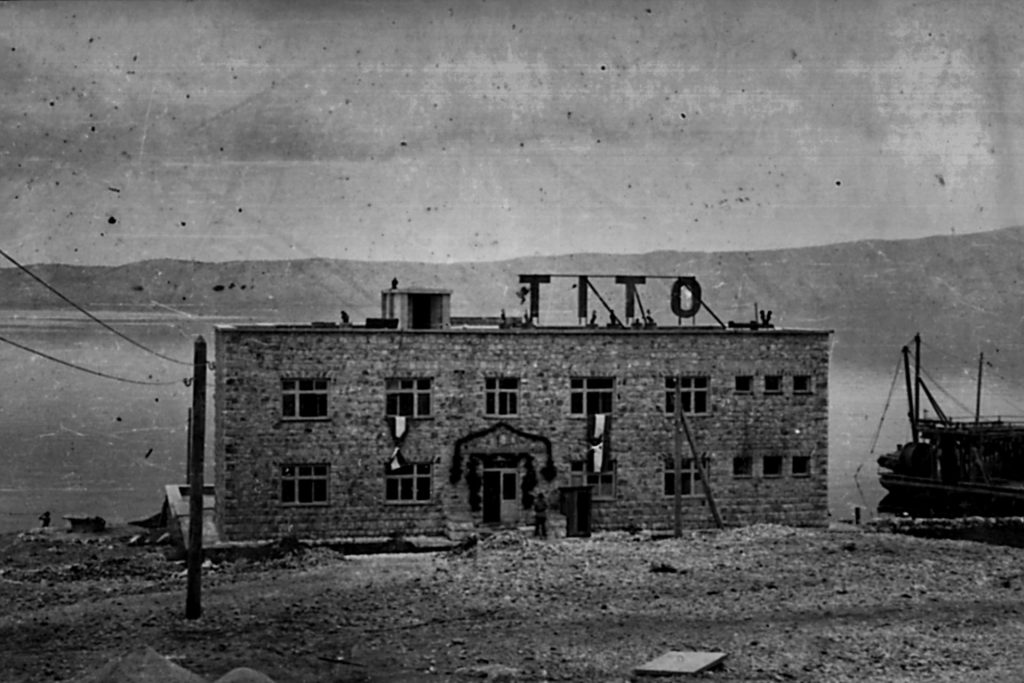

A three-kilometre road made up of tiny, neat stones, leading nowhere. It could be the perfect symbol of Goli Otok (Barren Island), which became a prison and torture camp for the political opponents of Josip Broz Tito, dictator of Yugoslavia between 1953 and 1980.

At least 16,000 people (other figures put the total nearer the 30,000 mark) were deported to this island, little more than a large rock resting in the sea off the Dalmatian coast, between 1949 (when he was premier) and 1956. After the rupture between Stalin and Tito in 1948, those not aligned with the regime were accused of being traitors for expressing the slightest dissent; many, branded as enemies of the people, ended up in prison without even knowing the charge.

Intellectuals, politicians, company directors, writers, and former partisans who had fought alongside Tito himself thus found themselves on Goli Otok to be “re-educated” by Ubda, the Yugoslav secret police.

The prisoners’ forced work lasted eight hours, in the scorching heat during the summer and freezing wind during the winter, but there was always the chance that at the end of the day they would be asked to work another eight hours “for Comrade Tito”.

As soon as they disembarked, new arrivals had to go through the stroj (path), a “welcome greeting” that involved passing between two rows of prisoners who raged at them with kicks, punches and spitting. They were treated inhumanely and forced to perform pointless tasks.

“They were forced to extract stones from a quarry and then run to throw them into the sea,” says Darko Bavoljak, president of an association named Ante Zemljar in honour of the partisan and writer interned in Goli Otok, which fights to preserve the historical memory of what happened. “It is not easy, because nowadays the Croatian government is not interested in digging up the ghosts of former Yugoslavia,” Bavoljak points out.

The deportees built everything with their own hands: the water tank, the buildings with the dismal cells in which they were locked up, the interrogation offices where they were tortured to confess to conspiracies they were not actually guilty of.

Confessing, however, was the only way to get out of there and return home. The ordeal could also be shortened by inflicting punishment on fellow prisoners. “The guards sentenced prisoners to death for trivial reasons, but it was always a prisoner who carried out the sentence,” explains Bavoljak.

The “repeaters”, those who were sent to the island for the second time, or the hardliners who did not want to bow down, were sent to a special prison, the Petrova Rupa. This was a pit with no roof, named after the first person to be imprisoned there, the anti-fascist Petar Komnenić, a leading figure in the struggle for national liberation, who died in 1957 from the consequences of his imprisonment.

Ubda’s objective was to bend these hypothetical political opponents of Tito’s regime, prostrating them with forced work or leading them to madness through the cruelty and senselessness of the tasks they had to perform: more than 4,000 died from torture or exhaustion. Those who resisted and were eventually released had to sign a document in which they pledged not to tell anyone about what they had seen and suffered at Goli Otok.

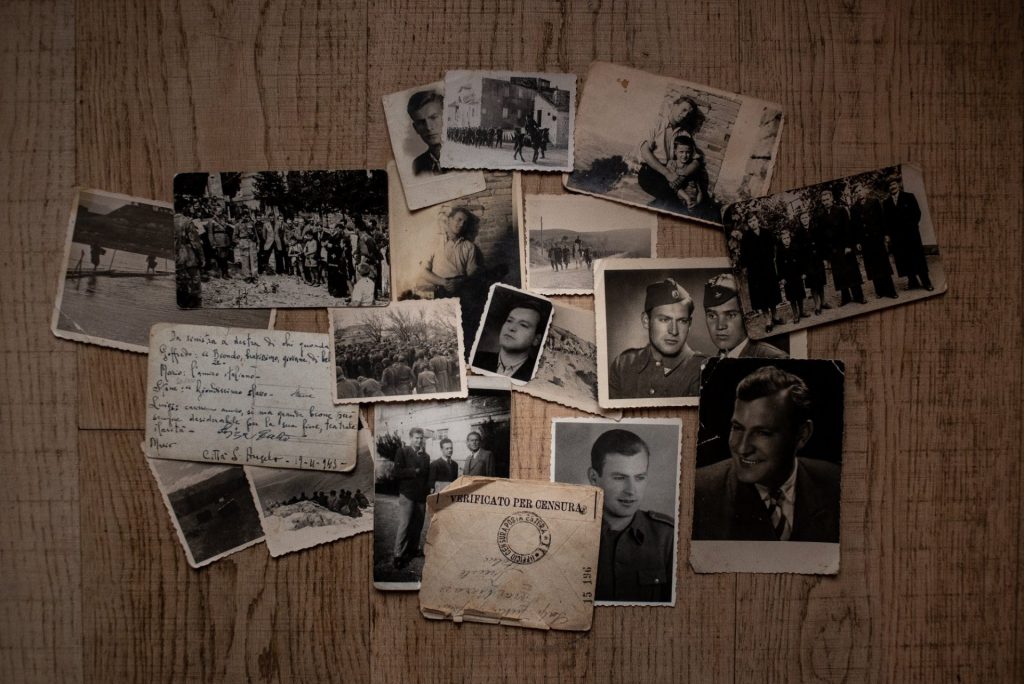

The survivors, partly out of a desire to forget the horror they had experienced, mostly respected the pledge of silence. Consul Ivan Antunac, later named “Righteous Among the Nations” for saving two Jewish families during the war, was deported to Goli Otok but, upon returning home, told his family nothing. “He only told me about it once, at a funeral, when I was already an adult,” recalls his son, Goran. “They had instilled fear in the veterans: they knew they were always being watched.”

Others, however, have testified, including Eva Grlić, a Jew, partisan and wife of the Marxist philosopher Danko Grlić (also deported to Goli Otok), who in her book Memories of a Lost Country tells the story of a life that encompasses the loss of her family in the Holocaust, the liberation struggle against Nazism and the years spent on Barren Island.

Their son Rajko, a well-known film director, remembers their kindness, their will to live: “For my parents, resisting violence meant that they did not burden us children with the suffering they had endured.”

After 1956, the island ceased to be a “political re-education camp” and was used as a prison for common criminals. The jail was finally closed in 1988.

Today, none of the island’s former prisoners are alive: their children and grandchildren are left to manage a complex legacy that the government does not care about.

These days, Goli Otok is just a distraction for tourists, who are taken for a ride on a little train amid wild sheep, to gaze at crumbling walls on which the writings that once praised Tito are fading, while the memory of the pain he inflicted scatters among the stones, barely pierced by a few brave shrubs bent by the wind.