“Faith is a heavy burden, you know,” says Max von Sydow’s knight in Ingmar Bergman’s 1957 masterpiece The Seventh Seal. “It’s like loving someone out in the darkness who never comes, no matter how loudly you call.”

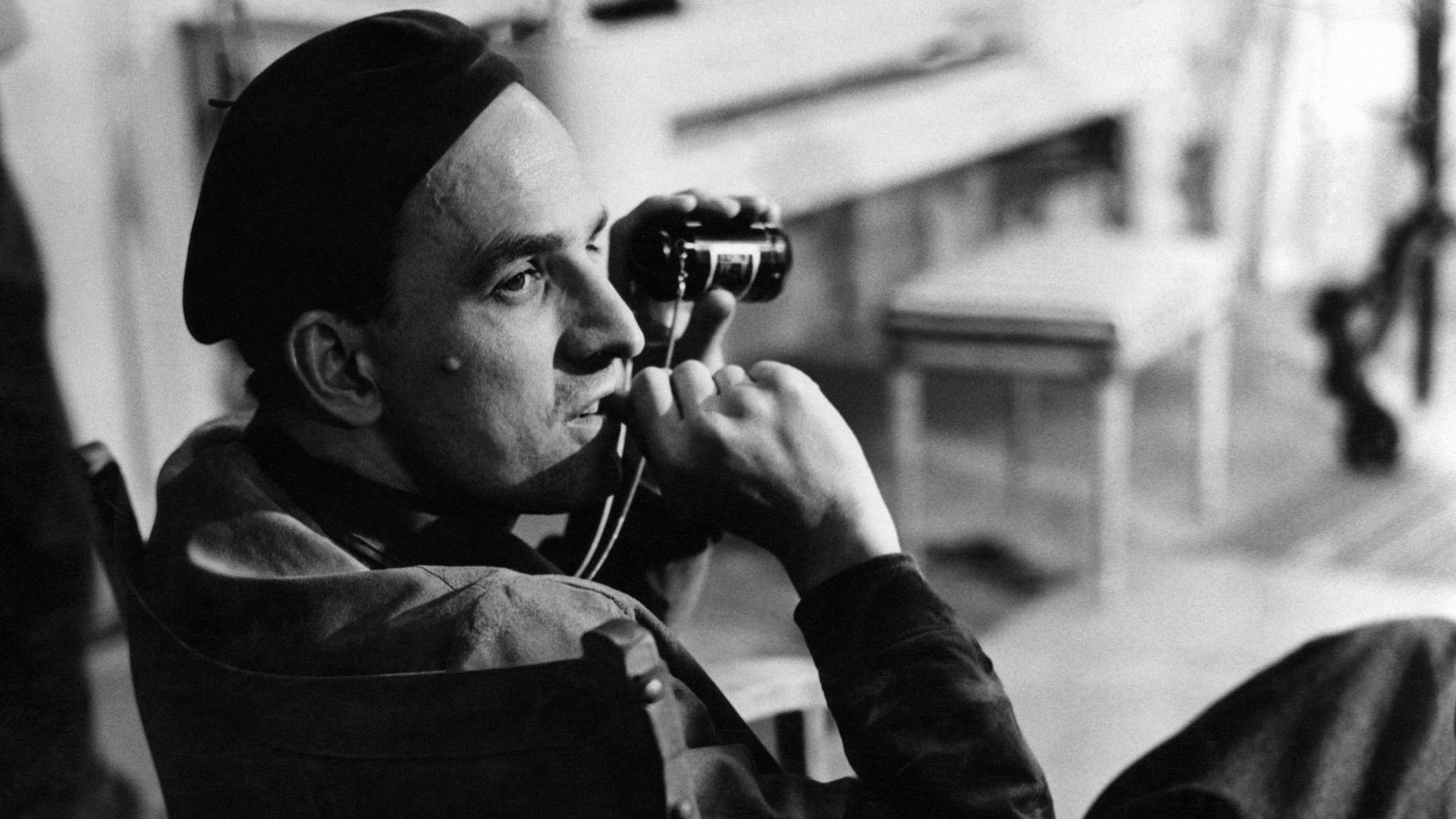

Often parodied, frequently copied, The Seventh Seal remains one of the greatest films ever made. The fact that debates continue as to whether it is not only Bergman’s own greatest film, but even the greatest film he made in 1957 (Wild Strawberries has a strong case) illustrates a legacy almost unparalleled in the history of cinema.

Thanks in part to its unforgettable image of von Sydow’s Antonius Block playing chess for his life against Death, The Seventh Seal always appears at or near the top of every poll listing the greatest films ever made. Often lampooned for being deliberately “arty”, The Seventh Seal is also unfairly regarded as depressing viewing.

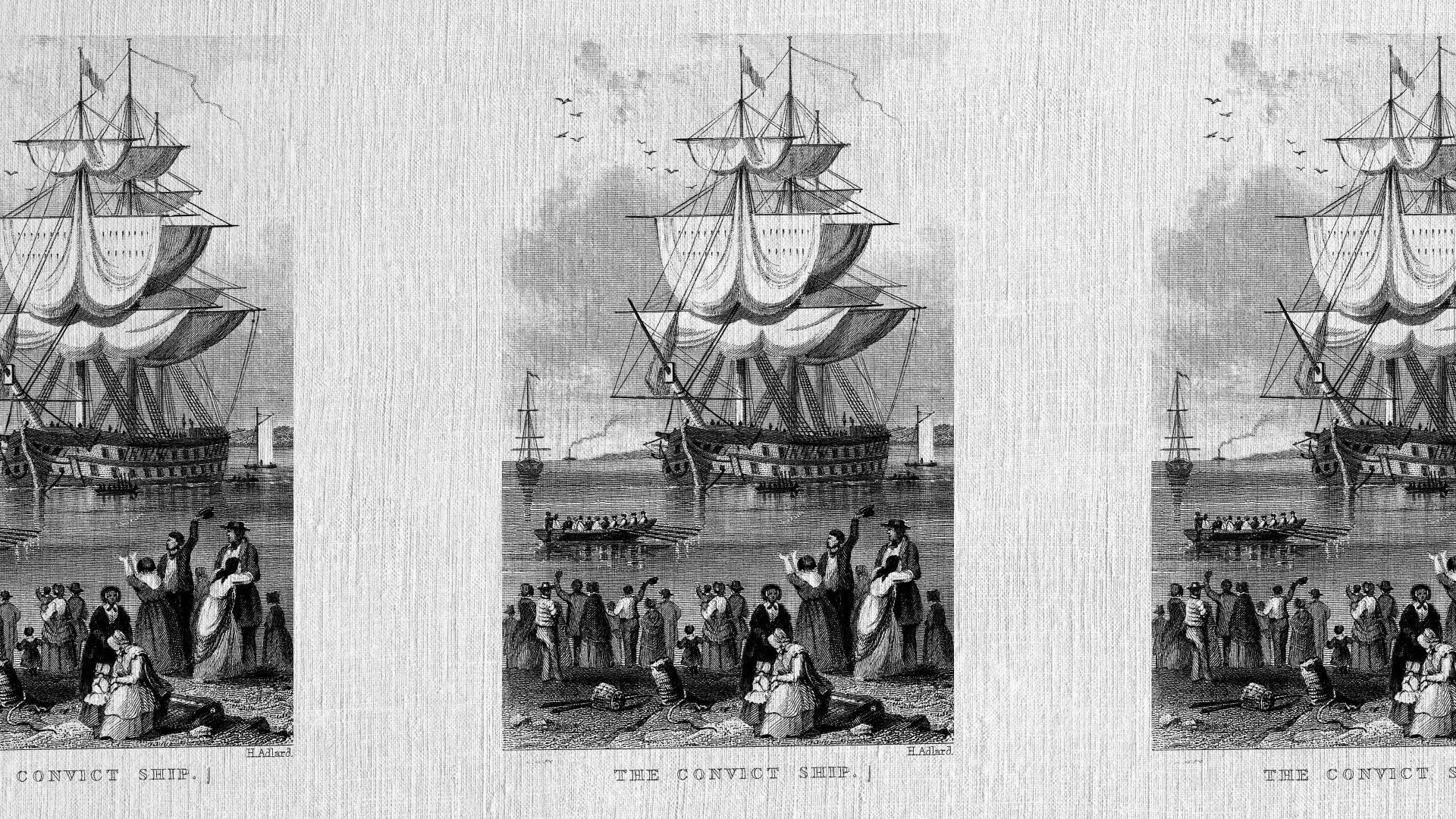

Granted, a soldier coming ashore from a decade away at the Crusades to find not only his homeland ravaged by plague but Death himself stepping across the shingle towards him is not the most upbeat of scenarios. Yet Bergman’s ultimate faith in humanity props up the film to leave a positive message: we all know we’re fated to lose our chess match with Death, but while we have the twin gifts of art and creativity we should make use of them rather than succumbing to a fear of death so intense it can suffocate life.

Made as the cold war was reaching its height, the themes of The Seventh Seal remain as relevant today as when the film was made almost seven decades ago. Such persistent relevance underpins Bergman’s greatness, forged by his innate ability to take epic, universal themes, strain them through his own story and experiences and offer them in adaptations made magical by the beam of the cinema projector.

Bergman traced the origins of The Seventh Seal to a childhood spent in the shadow of a Lutheran minister father, a disciplinarian to the point of abuse – the young Bergman was frequently beaten and locked for long periods in a kitchen cupboard for perceived transgressions like wetting the bed – who rose to become chaplain to the Swedish court.

Bergman would accompany his father to churches in remote villages where during interminable sermons he would become transfixed by the altar pieces, frescoes and stained-glass windows around him. On one occasion his attention was caught by a window depicting “Death leading the dance to the Dark Lands wielding his scythe like a flag, the congregation capering in a long line and the jester bringing up the rear”, a tableau that would comprise the final moments of The Seventh Seal.

These formative images were stored and left to simmer in the internal wrangle at the core of his creativity.

“I am very much aware of my own double self,” he said. “The well-known one is very under control; everything is planned and secure. The unknown one can be very unpleasant. I think this side is responsible for all the creative work, he is in touch with the child. He is not rational; he is impulsive and extremely emotional.”

A workaholic who lived on yoghurt and biscuits, Bergman was married five times and had nine children as well as a string of lovers, all the while creating at a furious rate. As well as making two of the greatest films of all time in 1957, that year he also directed his first film for television, staged four theatrical productions, met two of his future wives and conducted an affair with a star of both films, Bibi Andersson, all while still married to his third wife.

For all this external frenzy, it was the interior world where Ingmar Bergman was most at home, one he had devised in childhood after trading a box of tin soldiers for a magic lantern. For the rest of his life, he would withdraw into the security of his internal magic lantern where the constant battle between intuition and intellect played out.

“I make all my decisions on intuition,” he said in 1980, “but then, I must know why I made that decision. I throw a spear into the darkness; that is intuition. Then I send an army into the darkness to find the spear. And that is intellect.”

In 1960 while researching locations for Through a Glass Darkly, Bergman discovered the Swedish island of Fårö, fell in love with it, built a home there and effectively created the physical manifestation of his magic lantern.

The island provided a base for the rest of his life.

“This is your landscape, Bergman,” he imagined the island telling him. “It corresponds with your innermost imaginings of form, proportion, colour, horizons, sound, silence, light and reflections. Security is here. Do not ask why because explanations are just clumsy rationalisations created with hindsight.”

Fårö was his retreat, a place where he could even outrun the demons he sensed constantly pursuing him, driving him on.

“They know they can reach me in the early morning and if I stay in bed they invade me from all sides, but I cheat them because I get up,” he joked. “They hate fresh air. I walk quickly in all sorts of weather and they hate that.”

Between 1976 and 1984 he was displaced from his beloved island after being arrested for tax fraud; charges subsequently dropped. Deeply upset by the experience, Bergman relocated to Munich, growing more and more disillusioned. Fanny and Alexander in 1982 proved to be his last film as a director, during which Bergman fell out with cinematographer Sven Nykvist after refusing him permission to attend his ex-wife’s funeral. He also convinced himself he was ill with both stomach and testicular cancer.

“I want peace,” he said afterwards.

“I don’t have the strength any more, neither psychologically nor physically, and I hate all the hoopla and malice.”

He continued working in television and his beloved theatre, still urged relentlessly forward by the questions of faith and humanity he expressed most eloquently in The Seventh Seal but would never solve. Few directors have mined their internal anguish and lived experience as deeply as Bergman; even fewer turned them into cinema that changed the medium forever.

While his work in the theatre was arguably as successful as his work on screen, albeit without the same level of international acclaim, film allowed Bergman to come as close as he ever would to presenting answers to life’s conundrums. Or at least to asking the right questions. Cinema, he wrote in 1965, was where he found “a language that literally is spoken from soul to soul in expressions that, almost sensuously, escape the restrictive control of the intellect”.

What made his work truly sing, however, was the realisation that for all the frustrations of calling loudly into the darkness for answers that never come, it is all still worth it. As Jöns, Antonius Block’s squire, exhorted towards the end of The Seventh Seal, “But feel, to the very end, the triumph of being alive!”