On September 30, two Russian missiles struck a convoy of civilian cars queuing to enter the Russian-occupied territory of Zaporizhzhia. Thirty civilians died: mums, kids, taxi drivers. You can see their blood on the concrete from the drone footage of the aftermath. The close-ups people shot on their phones are better left unseen.

Later that afternoon, Vladimir Putin annexed the entire province of Zaporizhzhia – which he does not control – together with Donetsk, Luhansk and Kherson, following sham referendums staged at gunpoint. In a glittering Kremlin state-room, he warned the West that the people of these four regions “are becoming our citizens. For ever”.

He had, in short, celebrated the day of his supposed triumph by killing dozens of new Russian citizens.

Putin’s speech came after a welter of confusing signals. He released 200 prisoners of war. He threatened to nuke Ukraine. Alleged Russian sabotage destroyed both Nordstream pipelines, which transport Russian gas to Europe. In his speech he railed against the “Satanism” of the West, decrying transgender rights, and even criticised the allied bombing of Nazi Germany.

What are we to make of it? I think he is trying to de-escalate, while taking a chunk of Ukraine, leaving Europe’s populations permanently cut off from Russian energy. He wants to frame this for posterity as an anti-imperialist insurgency led by himself.

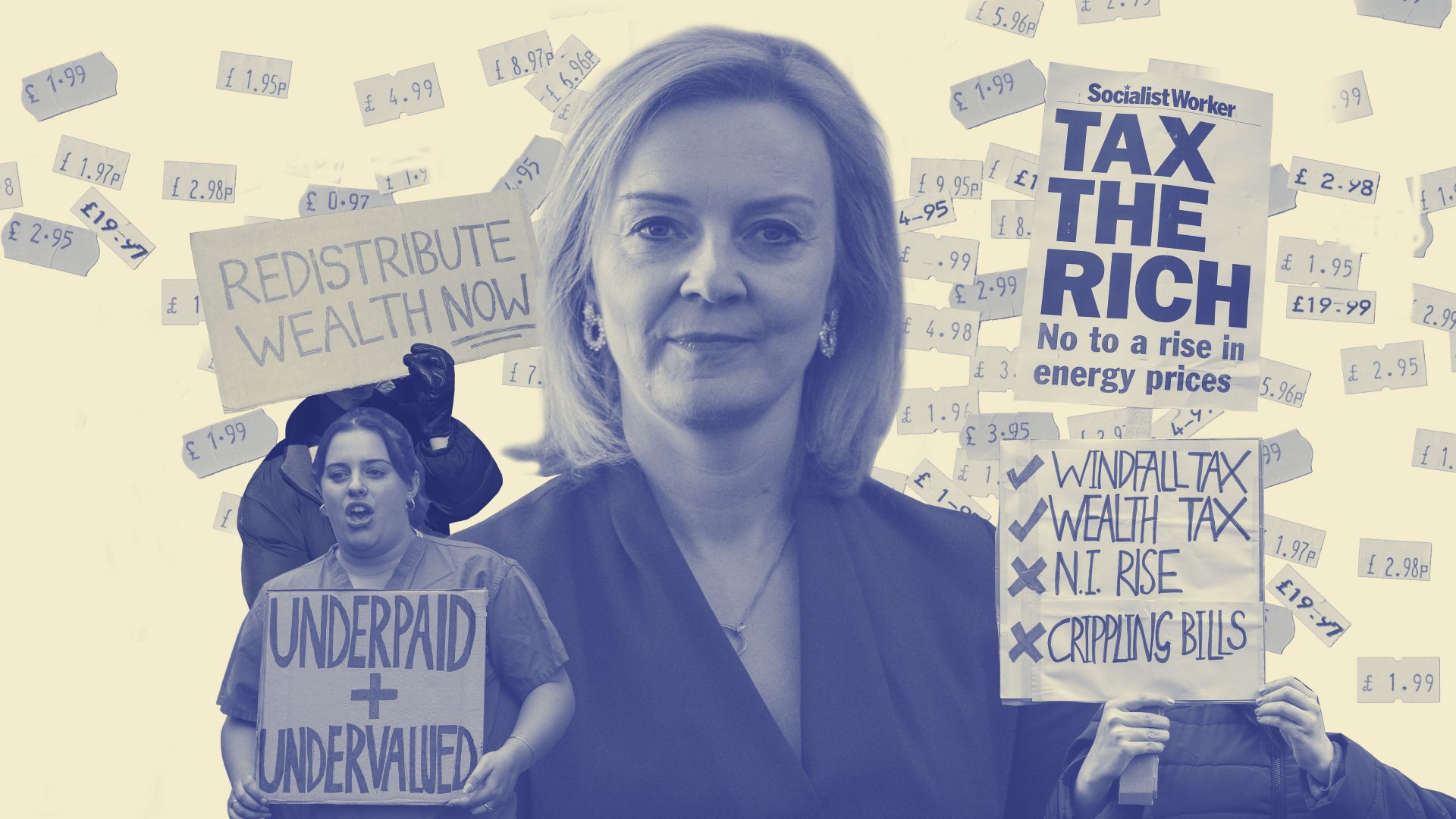

The nature of the trap he has laid is not obvious to many in the West. Here, the energy crisis has morphed into a political crisis in which – for entirely avoidable reasons – Liz Truss has destabilised Britain’s pension funds, tanked the pound, and plunged tens of thousands of mortgage seekers into uncertainty.

But this meltdown is as much an effect of Russian aggression as the massacre in Zaporizhzhia. It’s the outcome of an act of hybrid warfare.

First, Russia limited gas supplies to Europe. Then, as inflation soared, it cut them off. Now, very probably, it has permanently destroyed the pipelines. Next, it will use unrest over the cost of living and the political turmoil this has created to direct perfectly legitimate protest movements towards its own ends.

Putin told his spooks and generals: “We have many like-minded friends in western countries. We see and appreciate their support. They are forming liberation, anti-colonial movements as we speak. These will only grow.”

Maybe he was thinking of Angelo Sanchez, a Labour Party conference delegate. Sanchez denounced Labour’s support for Ukraine: “You are supporting the United States. You are supporting neoliberalism. You are supporting imperialism… You will be complicit in war crimes committed by the United States… You will also be responsible for worsening the living conditions of the working class in this country.”

Though Sanchez was booed off the platform, I was not surprised to hear a ripple of applause for him in the hall. Because Putin’s “like-minded friends” grouped around the Morning Star announced this exact strategy – of directing legitimate cost-of-living protests towards rejection of solidarity with Ukraine – in an editorial on September 2.

That’s what hybrid warfare looks like. Unlike a rocket attack it comes in phases, by stealth, using apparently innocuous events and ludicrous people.

We cannot do hybrid warfare against Russia, tit-for-tat. But we can exert economic pressure in reverse. So far western sanctions have seized the assets of Russian banks and individuals, frozen banks out of the SWIFT payment system, stopped the export of hi-tech goods to Russia and, most importantly, frozen $300bn (£268bn) of Russia’s foreign currency reserves.

Yet the Russian economy, on the face of it, has survived, because by hiking the global price of fossil fuels it has boosted its own revenues; and by imposing strict controls on the movement of capital it has restored the value of the rouble.

However, the real economy is creaking. The Russian car industry saw a 66% collapse in output. Real wages have fallen by 8%. As economists at Yale noted in August, almost all essential economic data is now withheld. Even the real rate of GDP collapse is impossible to understand because the real exchange rate of the rouble is obscured by manipulation.

Yes, China is buying oil from Russia – but at a massive discount. Yes, China is supplying imports to replace those lost through sanctions – but the value has more than halved since February. Though sales figures are suppressed, the Yale team estimates (by data-mining e-commerce figures) consumer spending has fallen by at least 20%.

The only reason Russia’s economic pain has not translated into revolution is the totalitarian state Putin’s rule has created.

But democracies with big, resilient and modernised economies have a weapon more powerful than any secret police: time. In less than six months, western sanctions have already wrecked Russia.

But we should have no compunction about wrecking their economy some more. Because Putin’s aggression is not just aimed at Ukrainians. It is aimed at us.

It is not realistic to expect Russians, right now, to rise up. The best and brightest have fled. The activists are in prison. The infosphere is shut down. More than 300,000 adult men are being dragged into conscript battalions and sent as cannon fodder to Ukraine.

People with power and influence are starting to feel the pain. More and heavier weapons for Ukraine, more ammunition, more open technical collaboration, more aid, and – yes – tougher sanctions will produce military reverses for Russia and the disorganisation of its elite.

Like the Russian front lines east of Kharkiv last month, the Putin regime will not implode gradually: it will collapse all at once under the steadily rising economic, social and military pressure.

Every Russian police chief, spy or general over the age of 55 knows the phrase “quantity into quality” – sudden revolutions as the result of gradual pressure were taught as Marxist doctrine under the Soviet Union. If we remain solid in Ukraine’s support, they will get to see the old textbooks come to life.