People who live on islands owe a great deal to boats, not least to small boats of the sort we have been hearing quite a lot about lately, much of it unjustly negative. And surely one of the major debts we owe to them here on our own particular island is our languages. None of the indigenous and quasi-indigenous languages of Britain would be here at all if they had not arrived on small boats from elsewhere – so linguistically at least we do have a lot to thank small boats for.

The Celtic languages arrived here from across the Channel about 3,000 years ago, probably travelling mainly from south to north. And the English language itself arrived in Britain about 1,500 years after that, also in relatively small boats, in this case mostly perhaps travelling from east to west across the North Sea. They brought speakers with them of the language which eventually became English from those areas of mainland Europe which today form parts of Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany and Denmark.

The boatmen, perhaps 30 or so per boat – and they probably were mostly men – were largely speakers of one of the West Germanic dialects which we now refer to as North Sea Germanic, which were also the ancestors of the Dutch, Low German and Frisian languages.

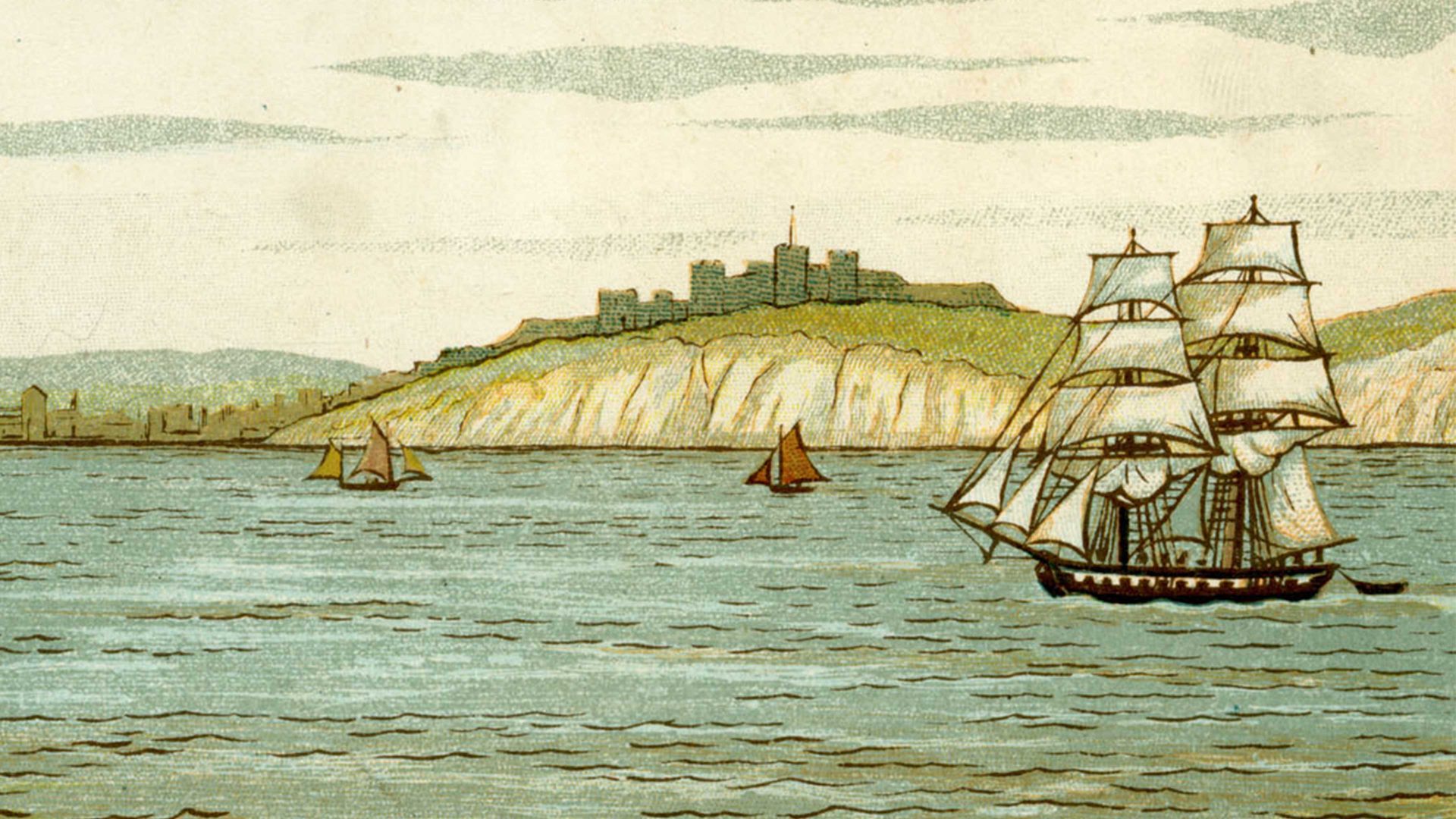

If we want to know where English was first spoken, then a good answer would probably be in Norfolk, Suffolk, Essex and Kent, in places where the boats were able to land in the east coast estuaries such as the Wash, Gariensis (The Great Estuary inland from what is now Great Yarmouth), the mouth of the Orwell by Harwich, and the Thames Estuary.

If we were to ask when English first came into being as a language, we can answer this question from a social perspective by saying that it began to acquire a separate identity of its own once the speakers of West Germanic who had initially crossed the North Sea from mainland Europe in their small boats first started to overwinter and then settle permanently in Britain. It was the permanent settlement of these people in eastern Britain which was eventually to lead to the break-up of North Sea Germanic into separate languages, and thus to the development of the English language.

If we tackle the same question from a linguistic point of view, then what that question is asking is, essentially: when did English first start breaking away from Frisian in terms of its linguistic characteristics? Frisian remains the closest linguistic relative of English, and some linguists have postulated a possible earlier single common North Sea Germanic language which they label Anglo Frisian.

The West Frisian language is still spoken today in part of the original Frisian homeland, West Friesland, the north-westernmost part of the Netherlands, and it has long been recognised as the language most similar to English: East Anglian fisherman used to have a rhyme which went:

“Bread, butter and green cheese

Is good English and good Friese.”

And Frisian seafaring folk too still have, or had until recently, a version of the same rhyme:

“Bûter, brea en griene tsiis

Is goed Ingelsk en goed Fries.”

The answer to this particular “when” question is “probably somewhere during the decades around 600AD”.

GARIENSIS

If you have ever taken a holiday, or even just a day trip, in a small boat on the Norfolk Broads, then you have been sailing on the territory once occupied by the Great Estuary or Gariensis, formerly one of the main entry points to England for boats crossing the North Sea.