The pound is falling, the cost of government borrowing is rising and the financial sharks are circling around chancellor Rachel Reeves. Last week, the yield on 10-year UK government bonds hit 4.9%. That’s five times what borrowing cost in the late 2010s and higher than anything Liz Truss achieved in her 49-day fiscal catastrophe.

Riots you can deal with. Online slanders from far right billionaires you can brush aside. But the bond market is, famously, the 800lb gorilla that can do anything it wants. It cannot be dealt with through spin.

Of course, the UK is not alone: bond yields are rising everywhere, as all developed world governments go deeper into debt. At one level it’s a supply and demand issue: demand for borrowing is giving lenders pricing power and they can afford to be picky.

But Britain is an outlier: Germany’s bond yield is around 2.5%; famously profligate Italy borrows at 3.7%. The USA has to pay 4.7% – which is in the same territory as the UK, but is said to reflect expectations of growth, not stagnation.

So why have we been hit the hardest?

There are three factors driving the problem. First, the Truss effect. Liz Truss’ mini-budget in September 2022 has impaired the UK’s fiscal credibility long term. It’s not that markets necessarily believe Rachel Reeves will pull a similar stunt. It’s that, if you are lending for between 10 and 30 years you want to be sure another Truss cannot come along.

Second, there’s a clear sense that Britain is going to have to borrow more than it expected. The Tories were running public spending on thin air in the last year of the Sunak government. Reeves has plugged the gap with the National Insurance rise and has borrowed close to the limit of what her own rules allow. But her plans are premised on growth at levels that just aren’t happening.

The bond markets notice this: they notice inflation-busting pay rises for public sector workers but flatlining private sector growth; they see inflation remaining stubbornly high. And they see Reeves boxed-in by commitments not to raise taxes that may not be sustainable.

Instead of public investment “crowding in” private investment, some bond buyers worry that the opposite happens: that the state ends up holding busted firms like Thames Water while having to bail out dozens of busted local councils, and the great private sector renaissance Labour promised never happened.

The third factor is market disorientation. Bond traders are facing a lot of unknown variables that weren’t in the textbook on the PPE course at university: will Trump hit the rest of the world with tariffs? If so Britain could be hard hit unless it swallows a chlorinated chicken-style trade deal. Will the security environment deteriorate? If so Britain will have to borrow more to spend on defence. Will China invade Taiwan? Will Farage win the next election?

The more complex the world gets, the more simple the answer for the 800lb gorilla: hike the cost of borrowing. With bond traders dazzled by the political uncertainty of the world, politics is driving decisions that would normally be economic.

To claw our way out of this is going to be tricky. Much of Labour’s economic plan is designed to deliver a long-term change in the growth drivers – more skilled workers, fewer people on long term sickness benefits, smart reindustrialisation and green energy. But to kickstart growth in the short term would mean pulling the kind of levers used in 2008-10: a return to quantitative easing: a relaxation of the Bank’s 2% inflation target; and micro-economic measures like a car scrappage scheme to take diesel-guzzling old bangers off the road and boost the sale of EVs.

Above all we need Labour take demonstrative actions that drive growth and wellbeing in 2025, not just in the long term.

In retrospect Reeves was absolutely right to go “belt and braces” in the last Budget: she raised taxes, raised borrowing and imposed tough rules on herself. Compare Labour’s autumn Budget to, for example, the Reform 2024 election manifesto and it is a model of responsibility.

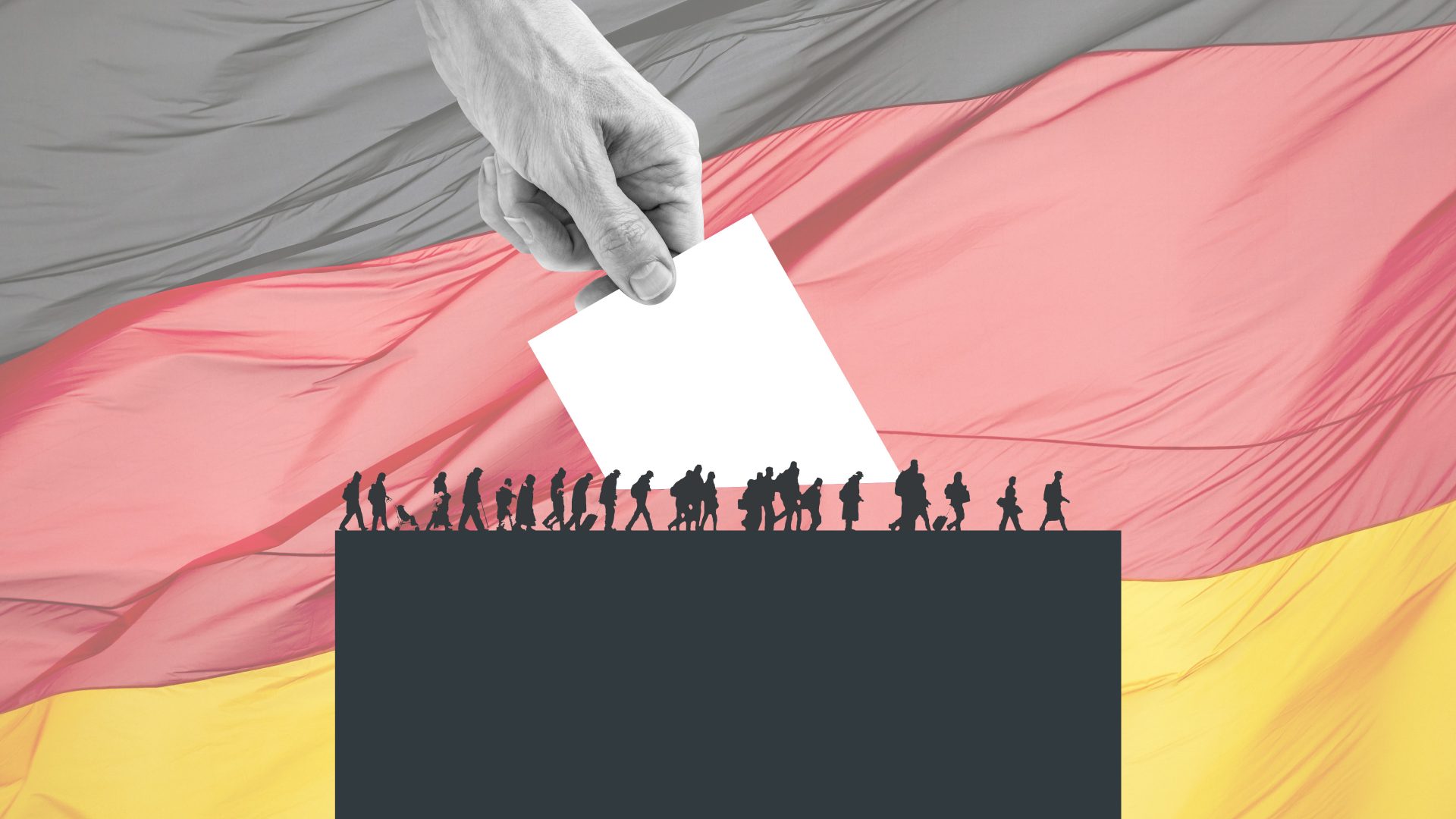

Reform, if you remember, wanted to borrow an extra £50bn, cut taxes by £90bn and cut public spending by £150bn a year. It was fantasy economics then, and is now. But the problem Reeves faces is that, with Reform now scoring 21% in the opinion polls, bond market traders are obliged to factor in the possibility that Reform might end up at some point running the tuck shop. That, too, hikes the implicit risks, and therefore costs, of lending to the the UK government.

The bond market threat should also be a wake-up call to the left and the Greens. Last summer the Greens pledged to hike public spending by £160bn and to invest £90bn a year. That would, at minimum, have required an extra £80bn of borrowing, each and every year, at the currently swingeing rate of 4.9%.

I am sorry to say, both to the Utopian socialists and the Utopian nationalists: the 800lb gorilla can’t be fooled. Right wing populism and Green fantasy fiscal policies are simply irresponsible, given the predicament our country has been left in.

We can, for certain, tax more – and I think Reeves will have to do so. We can, for certain, do more in the way of public ownership and state direction.

But if the population votes for a lie – which is what Brexit was – and is so wedded to the lie it forces politicians to accept it, and if you deindustrialise for decades and hand economic power to property speculators and asset strippers: this is where you have to start from.

We face the highest borrowing costs in the developed world because 30 years of free market economics have reduced our internal capacity for growth, because we cut ourselves adrift from Europe, and because our polity is fragile.

Whatever Reeves has to do to maintain fiscal credibility has to be done, but there is no reason it has to be spending cuts. If the facts change, she can – as Keynes said – change her mind on taxes. If the threat increases she can borrow to invest in defence and reindustrialisation. Rearm Britain and the economy will grow probably the only certainty we have.