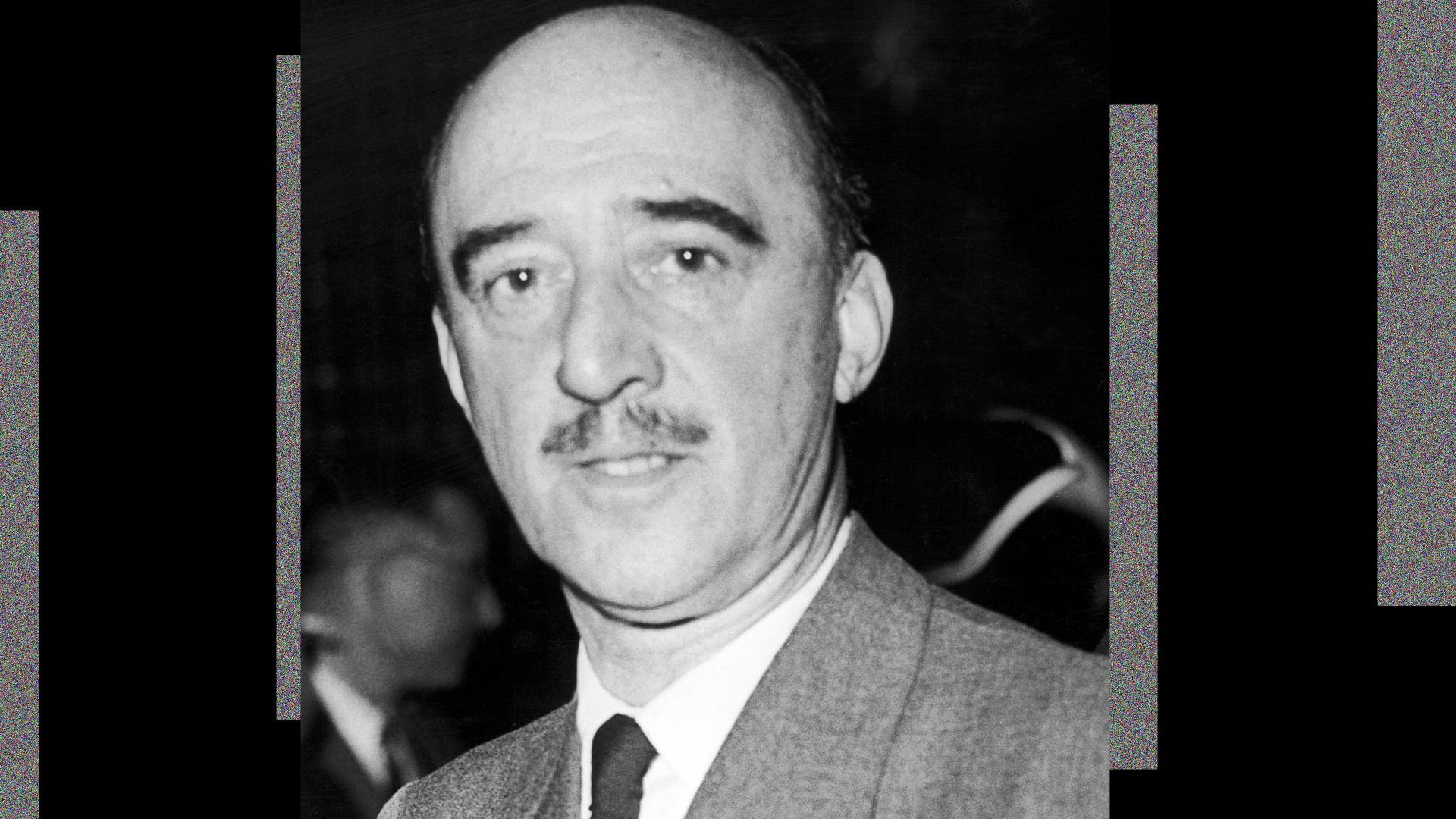

HV Morton is one of the biggest-selling British authors you’ve probably never heard of. At his peak in the late 1920s and 1930s his travel memoirs were shifting up to 200,000 copies of their first editions alone while he also held down a day job as a star reporter for first the Daily Express, then the Daily Herald. By the outbreak of the second world war, Morton was earning

£30,000 a year from his books, worth well into seven figures today, while

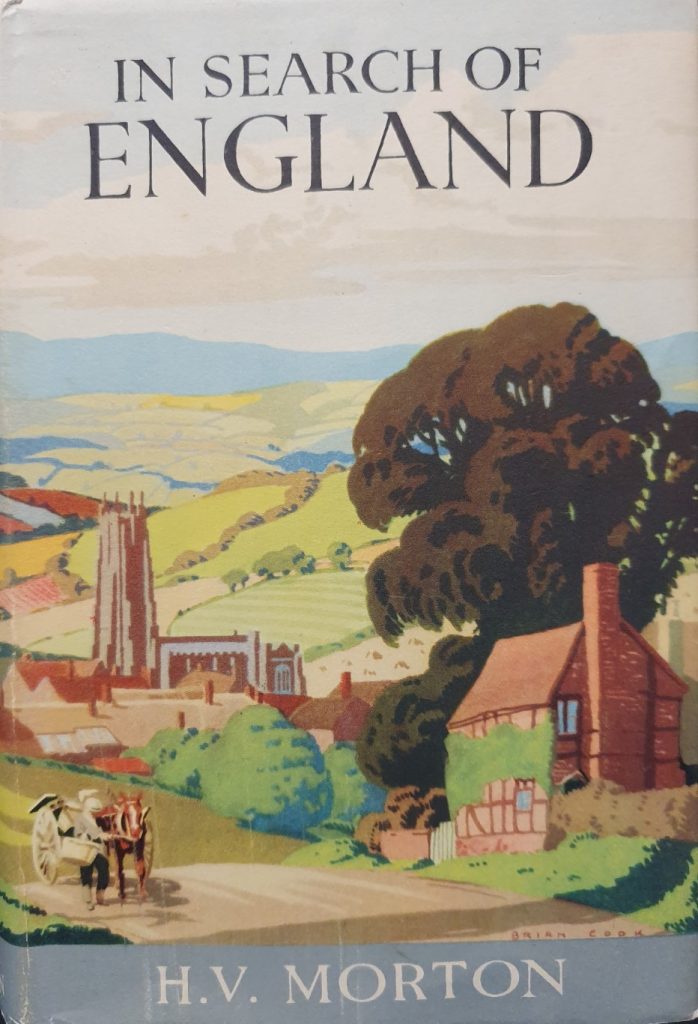

during his lifetime he sold upwards of three million books. His most successful, In Search of England, has remained continuously in print for almost 100 years.

When I first read Morton, who was born 130 years ago last week, I was

astounded by the quality and freshness of his prose. I’d picked up an

ancient copy of In Search of England, first published in 1926, in a second-hand shop somewhere knowing nothing about him. I’d never even heard of him, just spotted the title and as I was about to set out on a similar journey for my first travel book I thought I might find something useful.

Never has a writer previously unknown to me bowled me over like HV Morton did. In Search of England, in which he set off around the country at

the wheel of his two-seat “Bullnose” Morris Oxford, showed him to be warm, perceptive, knowledgeable, charming, funny and, most of all, he wrote like a dream. He mixed as easily with high society as he did with agricultural labourers and distilled a range of places and experiences into a few paragraphs that left me feeling like I’d been standing next to him the whole time. Morton was incredibly good company, as the best travel writers should be, shimmering out of the decades between us to show me the England he saw as vividly as if I was looking at it today.

I hoovered up more of his books. There were In Search of… volumes on

Scotland, Wales and Ireland, sequels to England and Scotland and a trilogy

of journeys in the Middle East. There were three small collections of pieces

he wrote during the 1920s for the Express exploring London. All bore the same Morton warmth and humanity, combining great learning, lightly

distilled, self-deprecating wit, an empathy for the everyman and a rare gift for concise, evocative description that’s bestowed on very few writers.

Outside the books, I could find out very little about the man himself but that didn’t matter because I knew him intimately through his writing. I discovered he was one of the leading journalists of the inter-war years and

covered the opening of Tutankhamun’s tomb for the Express in 1923. I learned he was so highly thought of that he was one of only two reporters invited to witness the top-secret 1941 meeting between Winston Churchill and Franklin D Roosevelt on a British warship off the coast of Newfoundland.

I also found that I wasn’t alone in my Mortonophilia and became a founder

member of the HV Morton Society, an online group set up for the small but

keen global band of Morton enthusiasts still enjoying his work. I bought up copies of his books wherever I could and pressed them evangelically on friends. I aspired to make my own books in his image, striving and failing to achieve his perfect balance of background information, on-the-spot impressions and including just the right experiences and incidents to tell the

story I wanted to tell.

Then, in the mid-2000s, a biography was published that changed everything.

Michael Bartholomew’s In Search of HV Morton was the first full-length biographical study, its author given access by Morton’s family to an extensive and previously unseen archive of his papers, letters and personal diaries.

This family approval could have turned Bartholomew’s book into a hagiography. It certainly wasn’t that. The avuncular HV Morton who narrated some of the best travel books ever written was, it turned out, quite

different from the Harry Morton who created him. Bartholomew’s research

revealed Morton to be a racist, an antisemite, an outrageous snob and a serial philanderer.

“The Jews who rule the world are determined to force us into war with Germany,” Morton told his diary in April 1939. The following summer he

wrote that a German victory would serve Britain right, how the nation needed a dictator and how “I loathe the very word ‘democracy’, which

merely cloaks self-indulgence, slackness, softness and snobbism, yet that is what we are supposed to be fighting for”.

In October 1942 he lamented that “Nazi theories of life and conduct – their attitude to Jews, the cult of hardness, to discipline, to service, to money – could not have been peacefully spread”, concluding that, “I simply do not believe that Nazism is all bad and all wrong. I believe it is the first stage of a spiritual revolution”.

He was put in charge of his local Home Guard unit at Binsted in Hampshire and referred to the men, many of them veterans of a first world war in which Morton himself had got no nearer to Flanders than Kent, as “ungrateful yokels”.

In 1948, convinced socialism was to be the ruin of Britain, he emigrated to

– wait for it – South Africa, in the same year apartheid became official policy.

Bartholomew was also given access to a notebook in which Morton recorded his sexual conquests, which numbered more than 100. Serially unfaithful to both his wives, he was a regular client of sex workers, noting a time in Paris when he managed to squeeze in a visit to a brothel in the 45 minutes available to him between changing trains.

His affairs were numerous, from brief encounters in hotel rooms to lengthy relationships. He even dedicated In Search of England to “TCT”, the initials of a woman who was not his wife. When he flew alone on his first foray to South Africa he managed to start an affair with the woman seated next to him on the aircraft.

He was 56 years old at the time.

Plenty of writers have turned out to be pretty terrible people, from Charles

Dickens to Roald Dahl to Ezra Pound to Enid Blyton, but this was personal. I

felt betrayed, like I’d been reading these extraordinary books under false pretences all along.

As well as his disgraceful opinions, the fact Morton the man was the antithesis of Morton the writer as presented in his books was bewildering. The kindly, funny, sympathetic narrator who revelled in the goodness of the places he saw and people he met had been totally convincing.

After reading Bartholomew’s biography it crossed my mind to throw out my beloved collection of antique hardbacks, but that felt like an empty gesture. It was too late for that. They remained on my shelf and their faded, scuffed spines in red, blue, green and black lurk there still.

As the 130th anniversary of Morton’s birth loomed I realised I hadn’t revisited any of his books since learning more about the man behind the title page more than 15 years ago. I opened my copy of In Search of England, written when the first world war was still fresh in the mind and the nostalgic myth of England as a land of thatched cottages, oak-beamed pubs and villagers strolling to evensong in the golden light of a late summer evening was really starting to take hold, and began to read.

Older and wiser as both reader and writer I noticed I could almost see his workings in some of the set pieces – brash, noisy American tourists make frequent stooges and sounding boards for Morton’s historical digressions, for example, whether they actually existed or not – and I knew from Bartholomew’s biography that the final section, a sun-dappled conversation with a clergyman in a rural Warwickshire churchyard, was almost certainly a

complete fabrication.

If the England he drove through wasn’t all a fiction it was a very selective one, the kind people thought they were voting Leave for, a timeless rural idyll with rigid social strata in which everybody knew their places. Notably, Morton’s journey explored no industrial towns or cities (although the sequel, The Call of England, did) and despite beginning his tour just as the General Strike got under way that remarkable, unprecedented national disruption warranted only a passing mention.

Yet the charm of the narrator, his wit, erudition, the ability to conjure a time and place from words on a page and sheer likeability still shone through. I can absolutely see why I fell in love with these books, I can see the influence they’ve had on my own writing and I can see why I find it so difficult to dispose of them despite knowing they were written by an out-and-out, copper-bottomed, Olympic-standard arsehole.

HV Morton, who in effect invented modern British travel writing, made me a better writer. Harry Morton, on the other hand, reassures me that, flawed as I am like everyone else, I am a far better human being than he ever was.

Who knows, maybe the HV Morton of the books was the person Harry Morton wished he could be. The bitterness and ignorance that consumed him and the vile prejudices that were so ingrained he invented an entirely different persona to present to the world almost make me pity him. Almost.