“You still don’t understand what you’re dealing with, do you?”

Soaked in the white liquid that ran through his veins prior to his decapitation, the android Ash, science officer on the Nostromo in Ridley Scott’s 1979 film Alien, has been revived temporarily by the ship’s crew to learn how they can kill the deadly creature running amok through the vessel.

“A perfect organism,” he explains. “Its structural perfection is matched only by its hostility.”

“You admire it,” says an incredulous Lambert, the ship’s navigator.

“I admire its purity,” says the android. “A survivor. Unclouded by conscience,

remorse, or delusions of morality.”

Ash’s words are not only the perfect encapsulation of the terrifying creature

at large on the Nostromo, they also represent the key to why Alien is such an

enduring piece of cinema: this is a monster drawn from our very worst

nightmares. Not only relentlessly hostile, it is free of conscience, remorse and morality.

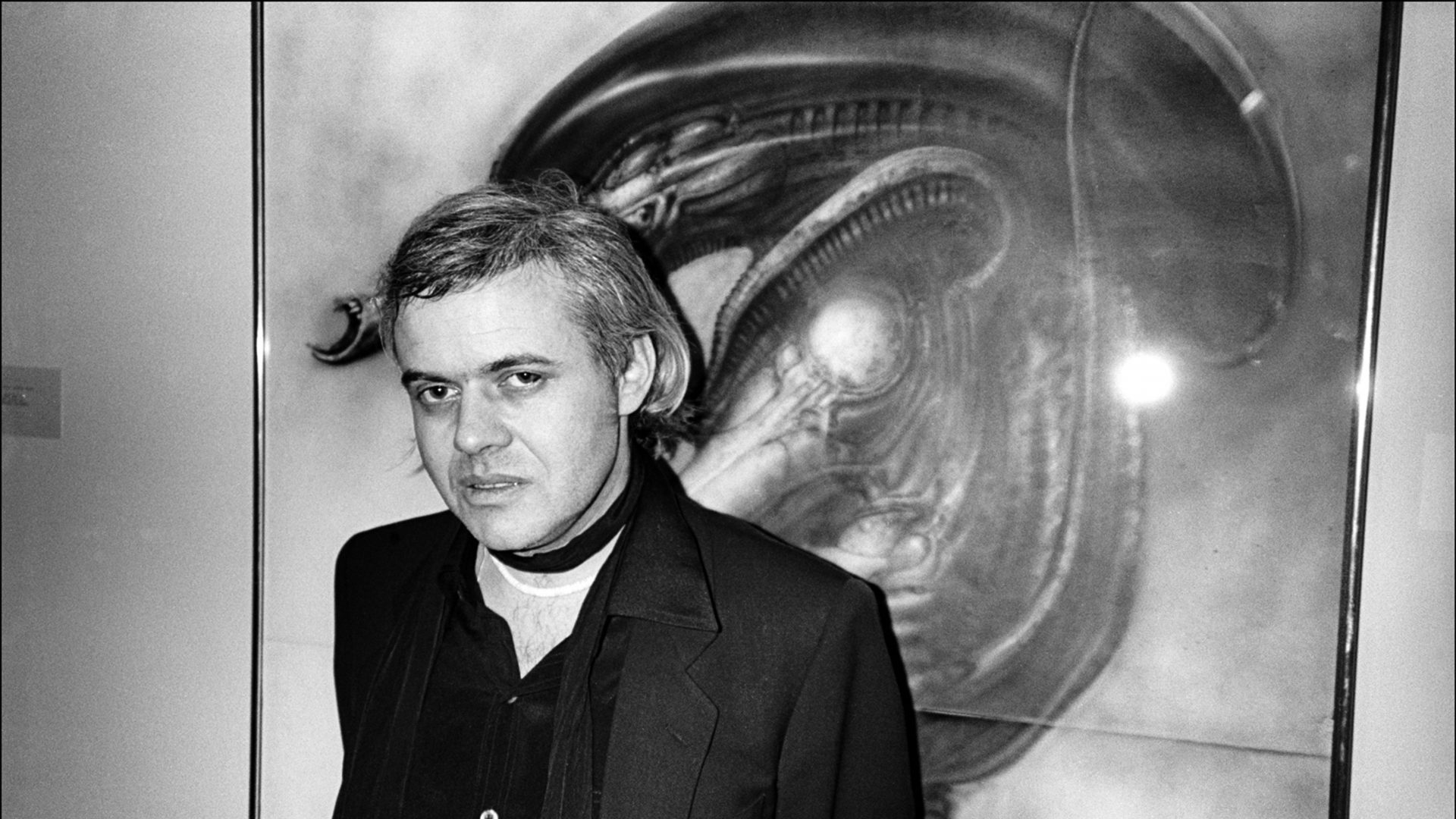

Nightmares were the business of Hans Ruedi Giger, who drew on his own to

create surrealist art that combined the three basic aspects of humanity – birth, sex and death – to produce works that veered from the merely unsettling to the outright terrifying. Most famously of all, Giger designed and created the creature that made Scott’s film so horrifying, as well as the planet and crashed spaceship where John Hurt’s Kane found the egg silo in which the creatures gestated.

Indeed, the entire first section of the film before the crew returns to the ship

with the stricken Kane is set deep inside Giger’s imagination, providing the canvas for the fear and suspense that builds almost unbearably until its famously gruesome release at the galley table.

Then there is the creature itself, seen mostly only in frightening glimpses of

its smooth, dome-shaped head, cluster of sharp, dripping teeth and lethal

talons like the blades of scythes leading its taut, prowling gait.

The alien was pure Giger and based on a painting included in his 1977, HP

Lovecraft-inspired book Necronomicon. Necronom IV was a much more overtly phallic creation than the alien it inspired, but the picture was still enough to have Ridley Scott immediately commission Giger for his film.

“I was shown the book in Los Angeles and when I was looking through it I nearly fell off the desk and said ‘that’s it!’” Scott recalled. “I have never been more certain about anything in my life.”

Giger won an Academy Award for Best Visual Effects, which should have been the stepping stone to further screen success, but his relationship with the film world would prove to be a difficult and frustrating one.

He was commissioned to work on Dune along with his friend and mentor

Salvador Dalí, originally intended as a far more ambitious project than the

version released in 1984. Dune was meant to feature a soundtrack by Pink

Floyd and a cast list including Orson Welles and Gloria Swanson, but the

David Lynch-produced project that finally appeared turned out to be much-reduced in scale, with only a fraction of Giger’s work making it to the screen.

Similarly, he felt ill-used by the Alien franchise, prompting the comment,

“Fox does not want to give me any credit at all”.

This sense of being an outsider, often with a sense of grievance, characterised Giger’s life and work from the beginning. He was difficult to

pigeonhole and was happy to keep it that way, content as long as there was

an audience for his creations in a cinema, at home with one of his 20 books or even at the tattoo parlour.

He felt no more at home in the art world, rarely exhibiting in conventional galleries and finding his most satisfying outlets in the Giger-themed bars he

designed in Switzerland; one in Gruyères as part of his own museum and gallery and the other in his birth city of Chur.

He produced some memorable album covers, notably piercing Debbie Harry’s face with skewers on the Blondie singer’s 1981 solo album KooKoo and in 1973 designing an unforgettable cover for Emerson, Lake and Palmer’s album Brain Salad Surgery but, as is often the case with the polymath, his versatility was regarded as a lack of focus rather than the multifaceted expression of an extraordinary talent.

Hence, despite a range of influential admirers from Dalí to US counter-culture guru Timothy Leary, who said: “Giger’s work disturbs us, spooks us,

because of its enormous evolutionary time span. It shows us, all too clearly,

where we come from and where we are going,” the artist could never shake off a general critical distrust.

Perhaps the mirror Giger held up to our histories and destinies prevented

him from enjoying wider success. His works were discomfiting hybrids

combining ancient history with a science-fiction future, overt sexuality with innocent beauty and machines with organic beings. All of it came from the dark recesses of his imagination and his troubled dreams: he kept a sketchpad by his bed in order to capture the creatures that stalked his nights.

Growing up in Switzerland, he was fascinated by an Egyptian sarcophagus

displayed in a local museum and when he was six years old, his father, a pharmacist, saw fit to present him with a human skull. This ultimate symbol of death suddenly inhabiting the very centre of what should have been untainted childhood innocence had a profound effect on Giger and he recalled being frightened by “holding death in my hands”.

The war also helped to shape the darkness of his outlook.

“I was born in 1940 so I could feel the atmosphere when my parents were afraid,” he said in 2009. “The lamps were always a bluish dark, so the planes

would not bomb us. Switzerland and Germany are close. The targets weren’t

always very well marked. I felt the fear of that very much.”

Having studied industrial design in Zürich and worked briefly as an interior designer, Giger turned to full-time art in his 20s and progressed from small ink sketches – he ascribed his lifelong penchant for dressing in black to this

period as it hid the ink splashes – to giant surreal canvases featuring the kind of outlandish creatures that captured Ridley Scott’s cinematic imagination.

He knew genuine darkness and tragedy as well as being able to draw it from the deep well of his subconscious. In 1975, his girlfriend Li Tobler, an actress with a history of depression, shot herself in their apartment at the age of 27. Her face had appeared in many of his works; it continued to do so long after

her death, continuing to inhabit the troubled dreams that inspired his art.

“A dream where I can’t get enough air, that’s frightening,” he said in reference to his Passages series of paintings towards the end of his life. “Or the kind of dream where I am stuck in a grave or something like that, that’s frightening too. But later I developed the paintings and they were very good for that. I got some sort of relief. I got no more bad dreams when I painted. It was helpful.”