On July 8 2016, a young woman was gang-raped by five men at the San Fermin bull-running festival in Pamplona. This horrific attack led to a legal case that would grip Spain and bring about changes in national laws relating to gender-based violence.

“Lucía” was raped by a group of young men who had travelled from Seville to the festival. The members – one of whom was an officer in Spain’s civil guard – proudly shared details of the attack among themselves via WhatsApp, in which they referred to themselves as “the wolf pack” (la manada).

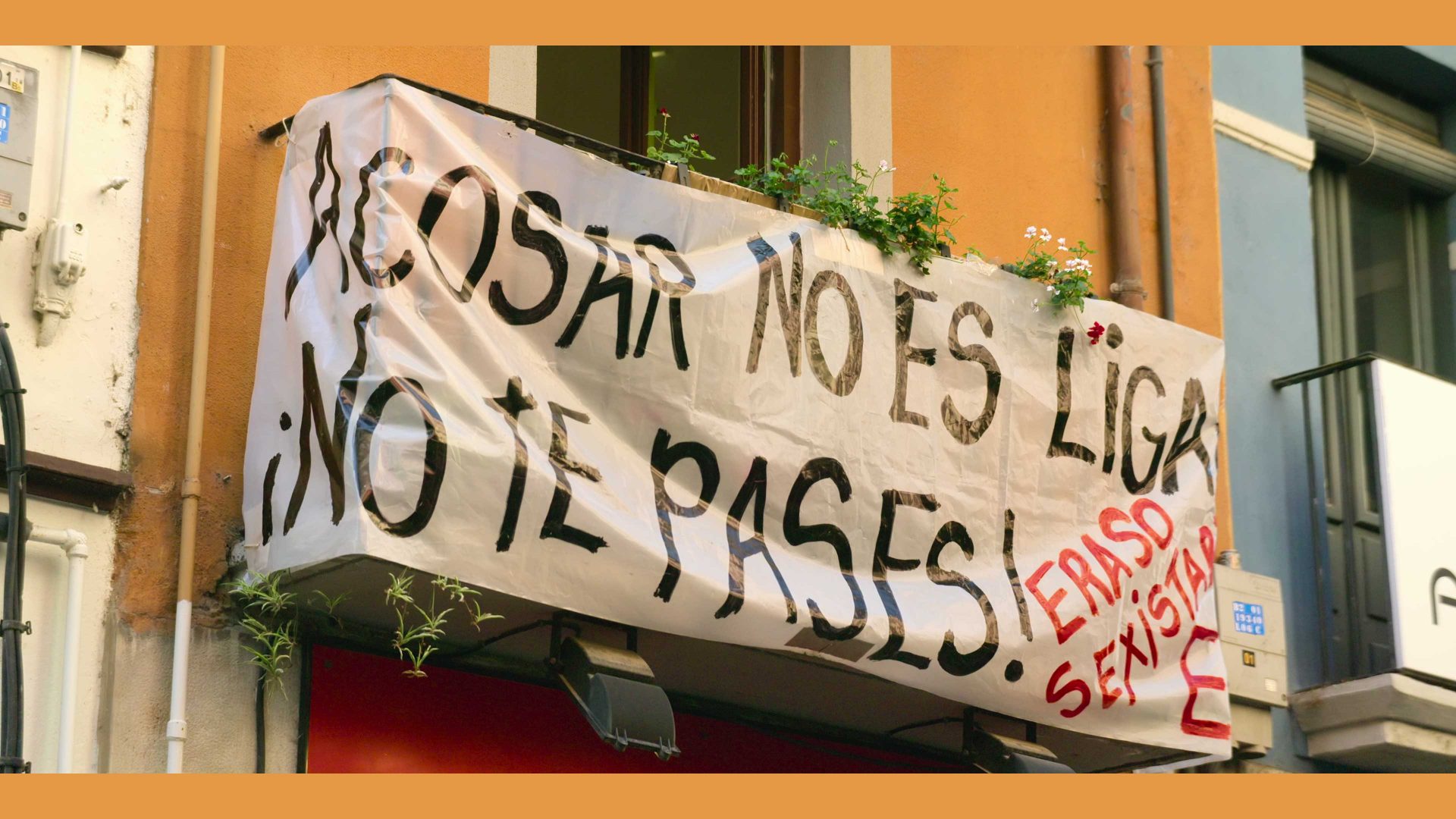

As the festival began, posters and banners hanging from the buildings in Pamplona’s old town issued warnings, reminding festival goers that sexual violence would not be tolerated.

These banners, and the rape that took place despite their presence, are a strong reminder of the gender politics and gender violence in Spain that continue to fuel the country’s “culture wars”, with feminists and anti-feminists taking increasingly polarised positions.

Progress in women’s rights has also resulted in a vociferous backlash; far-right party Vox has made repealing gender violence laws an election promise while frequently talking of feminists as “feminazis”.

The case became a key focus of feminist activism in the aftermath of the attack and subsequent trial. As it became clear this would be a trial by media, focusing on the victim as much as the perpetrators, hashtags and demonstrations gained momentum: #sisterIbelieveyou was Spain’s #metoo.

A trial that ended in April 2018 initially found the perpetrators guilty of the lesser crime of sexual abuse, because the prosecution was unable to categorically prove the victim had not consented. But many women looking on regarded the verdict with fury, horrified that Spain’s legal system was seen to be enabling gender violence.

After a wave of high-profile protests across the country and around the world, a subsequent appeal at Spain’s supreme court in 2019 secured the justice the victim and supporters sought. The five gang members were convicted of rape and their sentences increased from nine to 15 years.

Now, a powerful new Netflix documentary, You Are Not Alone: Fighting the Wolf Pack, forensically details the horrific story, laying bare the deeply entrenched sexism and misogyny that permeates Spanish society and culture.

Fighting the wolf pack

The film was written, produced and directed by wife-and-husband team Almudena Carracedo and Robert Bahar, award-winning directors of The Silence of Others, a film about the search for justice for victims of Spain’s dictatorship under General Franco.

For the filmmakers of You Are Not Alone, one of the difficulties in making a documentary about a culture wars case is that the story was framed by opposing viewpoints: those of feminists seeking to protect women’s rights, and anti-feminists fearful of the loss of men’s rights.

The young woman’s legal team stated that she submitted to the attack as she was paralysed by fear, while the men’s defence lawyer, parts of the media, and supporters of the wolf pack accused her of lying and being manipulative. In a media maelstrom, the truth becomes elusive. For this reason, the documentary makes the revelation of the truth its central mission.

A search for the truth

The process of making the film was painstaking and relied on watching and editing thousands of hours of archive material, interviews and CCTV footage, in a production that took three-and-a-half years.

Viewers follow the forensic evidence-gathering and detective work of the police in piecing together the actions of the rapists in this case, and a previous sexual attack they had committed for which they were later sentenced to an additional 18 months.

The film is a mosaic that takes a multimedia approach to ascertain the truth. It incorporates CCTV footage, media coverage, social media posts attacking and supporting the victim, multiple testimonies by police, officials, legal representatives, social workers, the mother of Nagore Laffage – a young woman murdered by a co-worker in Pamplona whose story is woven in – and the other victim the gang were found guilty of drugging and sexually assaulting.

Most importantly, it is anchored through the voice of the victim herself, “Lucía”, whose name has been changed and whose words are narrated by an actress.

The power of protest

Indeed, Lucía is not alone and draws strength and courage from the millions of women (and men) across Spain who took to the streets and social media after the trial to express their outrage at the crime, and the original sentence.

As with the protests against rape culture in Chile by feminist collective LasTesis, these protests went viral and global. News coverage of the wolf pack case reached international channels, and women protested in solidarity in Dublin, London, Rome, Lisbon, Berlin, Paris and Sydney – all shown in the documentary.

The film reproduces the tweets and hashtags shared in solidarity and chanted on the streets: “It’s not abuse, it’s rape”; “Sister I believe you”; “We are your wolf pack, you are not alone”. A follow-up hashtag #Cuéntalo (Tell your story) also went viral, allowing women across the country to share experiences of sexual assault.

We can credit the mass mobilisation of the women with the pressure required to successfully appeal the original flawed verdict, and to the subsequent “Only yes means yes” legal reforms.

As Lucía’s lawyer notes at the close of the documentary, “Society goes first and we follow.” This, then, is a collective story – as the film’s closing words of Lucía, reproduced from an open letter, reveal:

I want to give thanks to all of the people who, without knowing me, took to the streets of Spain and gave me a voice when many were trying to take it away from me. Thank you for not abandoning me, for believing me, sisters … No one should have to go through this. No one should have to regret having a drink, or talking to people at a party, or walking home alone, or wearing a short skirt. We all have to condemn the mentality this society has, where this can happen to anyone … If I’ve pricked the conscience of just one person, I will be satisfied.

Abigail Loxham, Lecturer in Hispanic Studies and Film, University of Liverpool and Deborah Shaw, Professor of Film and Screen Studies, University of Portsmouth

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.