Writing in these pages back in 2022 I claimed that the killing of al-Qaida’s (AQ) leader, Ayman al-Zawahiri by the US marked an end to President Bush’s War on Terror. I followed this with another claim: that this would not bring about the end of terrorism and that the terrorism we would face next in the West was right-wing extremism.

I concluded that the War on Terror may be over, but if we failed to address economic inequality and the lack of grassroots opportunities for young people in the most deprived areas of the UK, and, continued the political grandstanding on culture wars and immigration, that suggested to the same people that they no longer belong and there is an “us and them”, we would potentially encourage the opening shots of another wave of violence. I was concerned that the kindling was there, and another Zawahiri could light the spark.

The previous Conservative government accelerated the creation of an environment where right-wing ideology could take root. In the last week, we have seen that kindling catch fire. Not everyone who attended the protests that began in the wake of the tragic events in Southport was a far-right extremist, but as many of them descended into racist violence it was clear that a significant percentage held extremist views.

Keir Starmer is right to promise that the “tiny mindless minority” involved in the criminal activities that have constituted a large part of the protests will face the full force of the law. While this is necessary, there also needs to be recognition of the underlying causes of these protests or more will join this minority.

As an intelligence officer, I encountered terrorist suspects who had application forms for joining the police and military, or had previously been members of violent gangs. It’s not that they wanted to infiltrate the security services – they wanted something that working for those organisations offered. It’s not the cause that looks for them, they are looking for a cause.

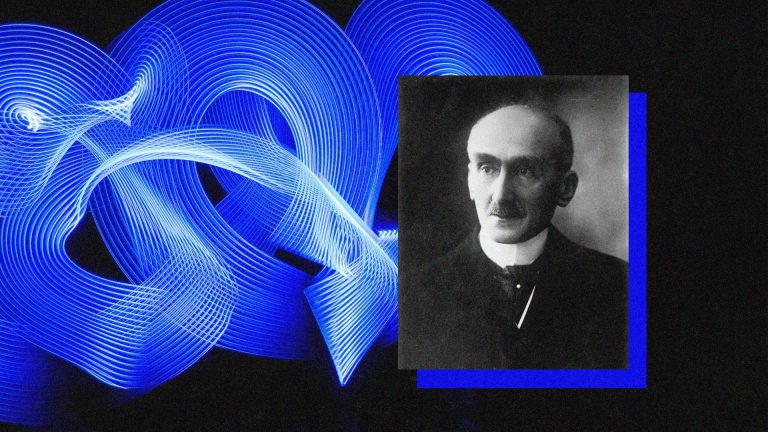

As Joseph Conrad claimed in The Secret Agent, his novel about anarchist terrorists at the turn of the 20th century: “The terrorist and the policeman both come from the same basket.” There will always be young people (predominantly but by no means exclusively young men) who search for meaning in adventure and conflict, and there will always be charismatic individuals who use them to achieve selfish ends by giving them a sense of belonging and a shared worldview.

Human beings need more than the satisfaction of our base needs and desires. We strive for status, belonging and meaning. We can find these in the service of political parties, religious creeds, nation-state groups, in the pursuit of wealth and material possessions, in the creation of art, in building a family. But when these other options are not open to you and then when you are told you are a victim and there are those to blame for your victimhood, you might choose to find status, belonging, and meaning in an organisation like Zawahiri’s. Or in a right-wing extremist group.

The more extreme the conditions you find yourself, the more extreme a solution you will consider. Over the last 14 years we have seen an accelerated growth of the same conditions, so rich for AQ’s recruitment drives in Muslim communities, in white working-class communities.

Islamic extremist groups have long recruited from society’s poorest. Economic inequality is a powerful motivator. In the UK, with the failure of the “levelling up” initiative, the government oversaw a period where inequality increased. There are whole communities that feel that they have been left behind by global economic forces from which their government has failed to protect them.

There are multiple generations who feel there are no opportunities in the towns where they live to achieve the life that others in more prosperous areas of the country take for granted. It is of note that some protests descended into looting. As jihadists ascend a group’s hierarchy, they often reward themselves with material wealth. As Zawahiri blamed the West and his own government for perpetuating inequality, on-line right-wing influencers, and even government ministers, have blamed immigrants for inequality in the UK.

Islamic extremist groups recruited heavily from countries where there was a lack of democratic freedom, positioning themselves as both victims and resistors of political repression. In the UK there is a general frustration at the political process, both the choices presented and the vast difference between numbers of votes and the number of seats won, most obviously in the case of the right-wing Reform Party.

There is increasing disdain for an elite, far-off bureaucracy, detached from the daily lives of voters. Delivery of Labour’s manifesto pledge to deepen devolution settlements for existing Combined Authorities and widen devolution to more areas, could help reengage disenfranchised communities.

Regardless, this won’t allay fears on the far right that the new government will accelerate the introduction of Cultural Marxism, the far-right conspiracy theory that describes intellectual efforts to replace Christian values with identity politics via a culture war.

In the West, the far right have positioned themselves as both victims and warriors in this culture war. They cast themselves as resistors to censorship on sensitive cultural and political issues, as society becomes more politically polarised, and defenders against attacks on aspects of the country’s culture and history that are still a source of profound pride for many.

Whilst in recent years there have been genuine examples of the restriction of needed public debate on several issues due to concerns over offending minority groups, both fringe and mainstream politicians have amplified the right-wing narrative of cancel culture, and the more extreme narrative that Western culture is under threat from widescale immigration and Cultural Marxism. The narrative, though, has taken root as there are grains of truth contained within it.

Instead of challenging it with arguments that stress the complexity of the challenges we face, successive Conservative ministers have used simplistic narratives in pursuit of political survival. Labour must avoid further bungling on issues viewed as key culture war battles and challenge the binary narratives on both sides of the political divide, encouraging reasoned debate on the limitations of free speech.

Labour should push dogmatists of all persuasions to accept that we can amplify the voices of previously silenced communities without silencing other communities and we can revise our understanding of our own history without rewriting it, accounting for our failures as well as remaining proud of our successes. Genuine multiculturalism is finding ways to live together, recognising the value of different ways of living, rather than enforcing any one way of life or correct way of interpreting the world.

These messages must be targeted at our young people. Of the twenty children arrested for terrorism offences in 2021 nineteen were associated with extreme-right ideologies. At the end of lockdown, headteachers expressed concerns over exposure to extremist material online when children were isolated. One serving a mainly white, disadvantaged community, said: “The kind of thing we are coming across is a really strong sense of us and them. The idea that if you are not white, your voice and presence are not as welcome.”

Replicating the global jihadi community, there is now a global extreme right-wing community, stretching from the US through Europe down to Australia and New Zealand. Russia lies at the heart of this community. Pro-Russian narratives are prominent in the global extreme right-wing community. Rinaldo Nazzaro, leader of the global far-right organisation The Base who this week advertised for a US-based leader for his organisation in the run up to elections there, is an American based in Russia. Echoing AQ’s goals, Nazzaro believes in the acceleration of racial conflict through violent means, to destroy society so it can be rebuilt (al-Qaida literally translates from Arabic as “The Base”).

Combating Islamic extremism, I saw the attempt to fit often nebulous and loosely connected groups into clearly defined organisational structures (this was what the agencies pursuing them were used to in their own image), but often interactions between extremists were of encouragement, knowledge sharing and the establishing of global narratives rather than evidence of formal structures. We are seeing this now with right-wing groups.

It is unclear if the initial Southport tweet blaming a Muslim immigrant by Channel3Now was deliberate misinformation but pro-Kremlin Telegram channels reshared and amplified the site’s false post as did right wing influencers who have international connections and use shared language and narratives. The accusations of “two tier policing” referencing policing at recent Pro-Palestine protests has previously been used in the US by the far-right around the BLM protests.

The immediate response to these protests should be focused on the restoration of law and order (although it should be noted that many jihadis were radicalised and built networks in UK prisons). To deal with the under-lying causes a response involving all civil society is required. We need investment in education, grassroots sports, arts and other activities that create belonging and meaning for children. We need to counter, rather than censor, far-right content that is perpetuated by nefarious on-line networks.

A counter-narrative must develop recognising the inequality global economic forces have created, allowing open and honest conversations on immigration (setting it within the context of our complex history, highlighting the many benefits and addressing concerns), and destigmatising a patriotism that allows self-reflection on our past while recognising our shared good fortune of living in the UK. More than anything we need to invest in the communities that are left behind economically and politically disenfranchised, focussing on empowering those locally to solve nationally neglected problems.

If we do not fill the economic, cultural and political void that so many communities now find themselves in, there are toxic ideologies that will.