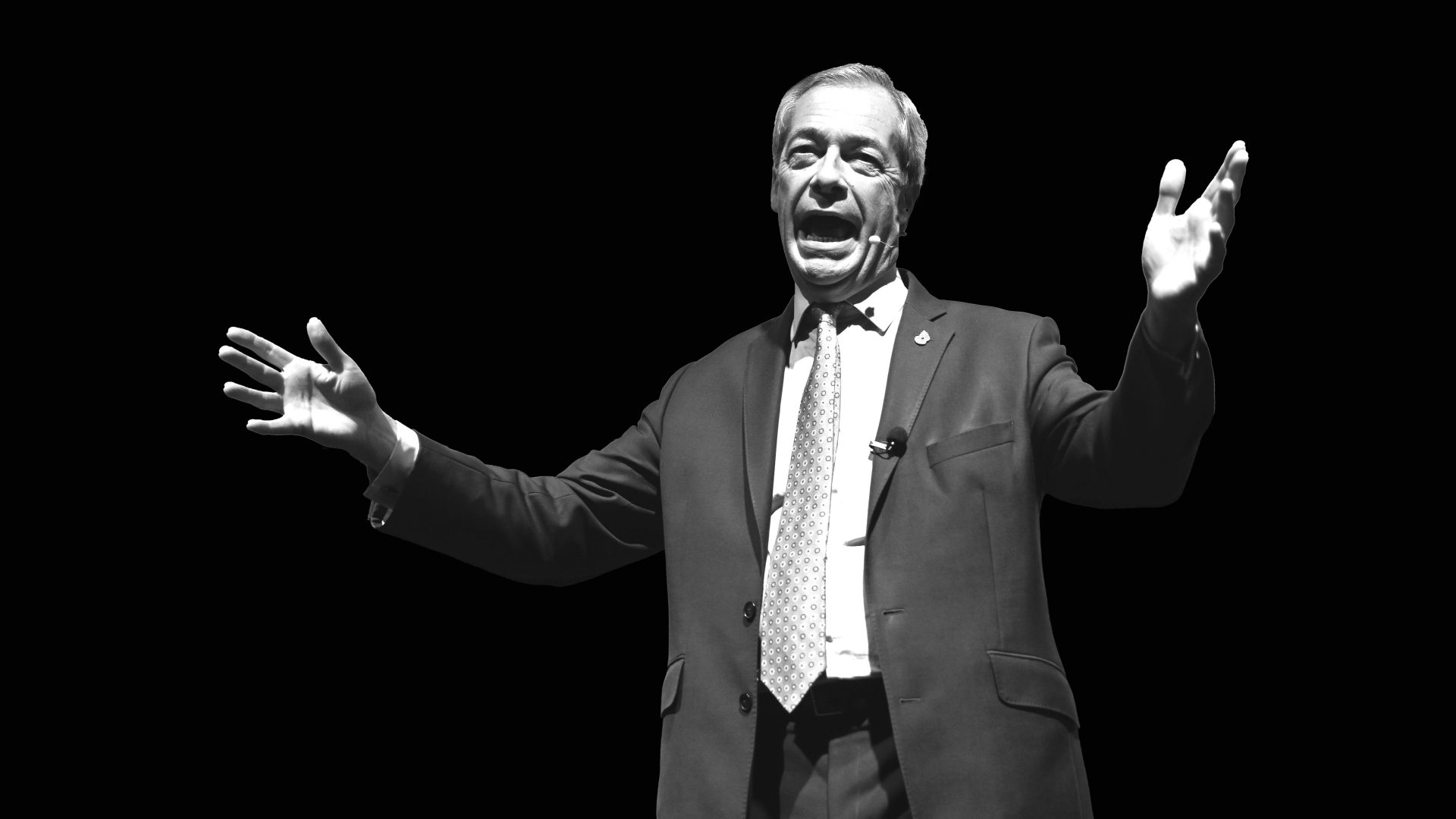

Those who thought 2024 would be the year populism started to beat a retreat have been seriously disappointed. There is Trump, of course, and the march of the European populists, and also Reform’s continuing ability to seduce the British public: having reached 24% in the polls, did Nigel Farage’s party ever really need the huge bung that Elon Musk was offering it?

We are in the throes of a populist surge – but how far will it go? Cas Mudde is a Dutch political scientist who has studied populism more closely than most. Recently he wrote on Bluesky: “I feel 100% certain that liberal democracy will prevail,” but then added, “… just not sure when.”

Of course, Reform is not an imminent threat to the Labour government, which is why, for Keir Starmer, there is a strong case for getting on with the job and ignoring the polls.

The next real test of Labour’s popularity will be in the local elections in May, and then the 2026 Welsh Assembly and Scottish Parliament contests. While the party is unlikely to achieve a lot in Holyrood (although it is doing better than many expected), it poses a genuine challenge to Labour in Wales. Both the main parties are struggling there, but cynicism about the ability of either to change much is particularly acute after Labour’s long and uninspiring stint in the Senedd.

In short, the threat from Reform, Musk and the broader populist right still feels acute. The dilemma of what to do about it is a challenge the left and centre of British politics cannot ignore, even as Labour would like to bask in its comfortable majority. And so the questions pile up: Reform constituencies have more potholes – is that a key to the problem? Why don’t people appreciate that crime has gone down? How do we confront foreign interference in British politics?

Out of all this anguish emerge several diagnoses of what needs to happen to neuter the Reform threat. The first is that making concrete improvements to people’s lives will ultimately ensure a second Labour term. You could call this group “the Deliverers”. Starmer’s new chief of staff, Morgan McSweeney, is a leading proponent of the view, along with the new general secretary Hollie Ridley.

Another group, “the Messengers”, thinks that Labour is unusually poor at getting its message across and needs to understand that the old ways of communicating aren’t working. These are often the people who lament Keir Starmer’s inability to connect, and yearn for him to tell a story about how Britain will thrive under a Labour government.

A third group thinks the root of the problem lies, broadly, in Britain’s constitutional inertia: first past the post, an elusive constitution, an often indefensible second chamber, the reluctance to negotiate a better relationship with Europe. Call them “the Constitutionals”.

What is indisputable is that the PM takes the threat seriously. Asked about Reform’s surge as he announced the government’s latest missions, Starmer replied: “This kind of politics feeds off real concerns.” In this diagnosis, there is no ideological shift to the right. “People haven’t become radical ideologues,” he added. It’s just that they’ve stopped believing the state can make anything better: Labour’s task is to prove them wrong.

The acknowledgement of “real concerns” is telling. Starmer knows he must convince these voters that he is tough on immigration, the issue that Reform voters identify as their top priority, and Labour’s stance has become noticeably harder. Starmer says he wants big reductions in both legal and illegal immigration and the government is ramping up deportations. A consequence is that a better deal with the EU is being held up by the fear that it would encourage more migrants and students to come to the UK.

Labour saw how the issue of borders hurt the Democrats in the US, and its position on immigration has been shaped by a determination to avoid the same fate.

But like many of the things Starmer has done since taking over the Labour party, it is also a warning to some of his internal opponents, many of whom are comfortable with immigration and hate it when Labour, as they see it, kowtows to an agenda dictated by Nigel Farage. Starmer’s claim that Britain had “open borders” under the Conservatives repelled many on the left.

“Not a slogan that can be coherently defended,” said Sunder Katwala of British Future. “I hope to never see that sort of thing from him again,” wrote the commentator Ian Dunt. Their argument is that you don’t fight Reform by aping Reform.

The Deliverers think this is naive. “It’s important that Labour does lean into it,” says Ryan Wain, executive director at the Tony Blair Institute (TBI). “The domestic political conversation around immigration is really important… It’s a tricky thing for progressives to talk about, but it’s good to see the home secretary step up those deportations of illegal migrants, and I think the Labour government probably could make more noise about it. The public needs to hear that. We have to be grown up about it.”

The issue of digital ID is one of the dividing lines between the Deliverers and many other Labour supporters. For the TBI, worries about privacy and an overreaching state are secondary to the need to know who has the right to work and claim benefits and who doesn’t. “It evokes memories of the ID card in the 1990s, but I think it’s different,” says Wain. “It means, if the Home Office were to go and visit a nail bar where there’s a disproportionate number of people who don’t have the right to work in the UK, they’d be able to very quickly verify people’s identity.”

One of the reasons Labour keeps talking about immigration, however much some of its supporters dislike the subject, is because it is getting harder to get across the government’s view on that issue. The right wing press is not interested in boosting Labour’s efforts, unless it provokes a split on the left. The Guardian and the Mirror would prefer not to talk about it. Key speeches go unnoticed, especially when Netflix is more appealing than News at Ten.

For the Co-operative branch of the Labour movement, the imperative is to get out of Westminster and start rebuilding the things that were lost during austerity and the pandemic. Devolution is one of the ways they want to do this, but they stress the importance of local people taking charge of their own projects.

Caitlin Prowle is a former Labour staffer who is now head of politics at the Co-operative Party. She sees the August riots that began in Southport as the result of social atomisation and the frustration of people with no physical stake in their community.

“There’s been a decimation of community spaces, and the reasons for that are pretty obvious – around austerity funding, the privatisation of spaces, the closure of libraries, community centres and youth clubs – those physical spaces where different parts of the community would come together just aren’t there anymore.”

This phenomenon was first identified a quarter of a century ago by the US political scientist Robert D Putnam, who put the blame partly on TV. Then Covid made Britons, especially the elderly, more likely to stay at home.

Reform know this, Prowle says, and are digging in on the ground in communities where they feel they can make headway. In the past, Reform politicians have been scathing about food banks, suggesting they attract freeloaders. But the Reform branch in Braintree held a foodbank collection this Christmas.

She praises a community-owned venue in Birkenhead. “It had been a target for anti-social behaviour. A group of local people bought it and they now run it as a gig venue. The profits are reinvested in the business, but as well as that they have a whole programme of community-focused events, mum and baby, music tech.”

Prowle says the work can’t be done by the well-meaning middle classes who think the less well-off wouldn’t manage it by themselves. “It’s about normal people owning things… working men’s clubs are traditionally co-ops. For a lot of working-class men, their role in running the club was saying: ‘I’m not just a labourer, I’m involved in running this asset’.

“Do I think this is the policy that will solve the rise of the far right? No, but I think it is part of the solution.”

Running through these conversations was the fear that the north, and the former red wall particularly, is the place where Reform could take off. “They didn’t really see Southport coming,” says Alan Finlayson, a professor of politics at the University of East Anglia. “And it will happen again.”

Finlayson has coined the term “reactionary digital politics” for the ways in which the populist right spreads its messages online. “Digital gives you a sense of empowerment,” he said. “It’s really good at making people feel part of the resistance. It’s often full of reading lists, keep fit, so you’re strong. It’s connecting your personal being with this broader politics, whereas mainstream politics says: ‘We’ll do this’.”

Reactionary politics is not tied down by the need to agree on specific ideas or policies that would improve things. In fact, its default position is that the government already does far too much. Instead, it is defined by what it is reacting to – the belief that equality and rights have “gone too far”.

People are avoiding traditional news sources and can instead follow up whatever ideas they come across. “They’re looking for answers at any time of day, and it’s very easy to find these kinds of positions being articulated. The people making a living from this are not tethered by party rules or traditional journalistic roles.”

Yet Labour, Finlayson says, is still relying on the old ways of reaching voters. The methods New Labour used are still prized, and there is an abiding distrust of social media that dates back to the way most of the current cabinet were sidelined during the Jeremy Corbyn era. “A centralised media operation is brittle in this kind of environment, because you’re trying to control the signal, and you can’t do that in a decentralised world. The instincts of a party are to control. What you need is for supporters to engage.”

What is missing from Labour’s top-down communications operation, he argues, is “a politics that presents some kind of meaningful future vision that people can orient themselves around”.

Easier said than done – and there was certainly not much evidence of it in Labour’s December relaunch. “We invite the British people to join us in the mission of national renewal,” wrote Starmer in the Plan for Change. But the opportunities to do that are not tempting. Visitors to Labour’s website are invited to join the party, gamble in two different prize draws, read the manifesto or sign up to a mailing list. Instead of the empowerment promised by reactionary digital politics, it offers only a tedious passivity.

This is where the Constitutionals come in. For them, Labour is far too timid in ambition and is losing votes to the Greens and Lib Dems as a result. They want the new government to reshape the state and seize the opportunity to buttress British institutions against any future populist government. After all, when will the chance come around again?

Constitutionals remember when Boris Johnson prorogued parliament to “get Brexit done” and ask why Britain’s messy constitutional arrangements allowed it to happen. They point to the way power is concentrated in London and the reluctance to give mayors the ability to raise their own taxes or take meaningful decisions about their region. They wonder why Britain can’t rejoin the single market when it would clearly boost growth.

Warning about a “doom loop of volatility” (as the Compass thinktank puts it), they want Labour to bring in proportional representation. Often, they agree with Gordon Brown that an elected second chamber would help to restore trust in politics. And none of these things, they point out, would trouble the Treasury too much.

One of the other proposals Brown set out two years ago in his Commission on the UK’s Future was to enshrine certain social rights in a constitution. The idea stemmed from his anger that the Conservatives had allowed poverty, and child poverty in particular, to rise. Brown proposed the right to free healthcare and emergency treatment, free primary and secondary schooling, “decent accommodation” and that “no person should be left destitute”.

Free education for under-18s aside, no one can pretend that Britain is in a fit state to provide these things. Brown acknowledged it would be challenging, and that the government and the courts would have to thrash out what was meant by “decent” and “destitute”. The constitutional lawyer Colm O’Cinneide has pointed out that it was not clear whether the courts would ever be able to enforce such rights. But the important thing, Brown argued, was to put them into law so that it would be far more difficult for any government to take them away.

There is no doubt that the new government would like to be able to provide these things. A younger and more idealistic Starmer might well have campaigned for them. But there is no intention of putting them into a constitution. “I’d be really surprised if there’s any movement in that space,” says Morgan Jones, a journalist and former Labour aide. Similarly, “the membership loves PR but it’ll never, ever happen.”

And the reason the Labour leadership wants to stick with first past the post is obvious. Under the current system, Reform has five MPs and no clout. Under PR, they would be able to form a coalition government with the Conservatives.

Of course, there comes a tipping point in FPTP multi-party systems when an insurgent can break through and win lots of seats. But tactical voting served Labour well in 2024 and there is no reason to think it won’t do so again.

Was it important, I asked the constitutional experts at a recent Centre for British Democracy event, to try to bolster the constitution and enshrine rights that a future populist government might take away? The wonks sounded resigned. Ultimately, if voters elected a despot, the existence of the constitution afforded relatively little protection against whatever they wanted to do.

As Finlayson points out, the whole point of the reactionary digital right is to attack the idea of legally enforceable rights. Would creating new ones really embed them in British life – or would it create a class of “paper rights” that were impossible to enforce, and further erode people’s confidence in the rule of law?

For the Deliverers, who are now directing the Labour party’s operations, there is no way to defeat Farage except by addressing the causes of voters’ unhappiness. It should help that on many of the issues that cause voters the most pain on a day-to-day basis, Reform is feeble. Its plans for the NHS are essentially a series of tweaks to taxes — zero basic rate income tax for newly-qualified frontline NHS and social care staff, a 20% tax break for people who go private, and writing off student loans for those who work in the NHS for a decade. The party has nothing to say about the crisis in dentistry and the suffering it causes.

But the real trip to Big Rock Candy Mountain comes in Reform’s plan to end waiting lists. Anyone who can’t see a GP within three days, a consultant within three weeks, or be operated on in less than nine weeks would be entitled to a voucher for private treatment. It is, of course, unclear how this would enable the NHS to speed up appointments, or indeed how private providers would deal with a vast influx of patients — apart from shoving them to the back of the queue and billing the NHS as much as they could get away with.

On social care, Reform demands a royal commission (which Labour has now announced) and on A&E, it suggests “a campaign of ‘Pharmacy First, GP Second, A&E Last’.” NHS managers must have been kicking themselves that this one simple trick for cutting waiting times never occurred to them.

On schools, Reform’s main policy — 20% tax relief on fees — is not just expensive and aimed at the rich, but is likely to be extremely unpopular. The papers may hate Labour’s decision to impose VAT on school fees, but it polls extremely well.

Reform did not respond to a request for comment on how it intends to counter Labour criticism. But Nigel Farage may already be starting to regret his former eagerness to please Elon Musk. The billionaire’s interventions in British politics are becoming ever more deranged. In early January he demanded the release of the jailed far-right activist Tommy Robinson, a man who goes too far even for Farage. Musk, no doubt enjoying his neediness, then demanded Farage’s own removal as leader of Reform.

All this would give plenty of ammunition for Labour to attack Reform, if it chose to do so. Starmner’s recent comment that “a line has been crossed” by Elon Musk in his remarks on the Labour MP Jess Phillips, shows that he is not afraid to confront the populist menace head on.

But when it comes to wooing voters, the approach has to be a little different. “You don’t harangue them, you go for bread and butter issues,” says Jones. “We need to connect and deliver,” says Wain, baldly. It is not an inspiring slogan. But for the moment, it is the one Labour clings to.