First, the preparations were held up by a huge snowfall that temporarily blocked out the sight of Mont Blanc, looming five miles away. Then a week before the first-ever Winter Olympics got under way, 100 years ago this month, a thaw set in that turned the ice rink into a lake. Several top skaters had already decided to skip the event in favour of the world championships, held in Davos just a few days earlier.

Meanwhile, the Germans as a nation had been excluded and the Nordic nations had not wanted to turn up in the first place. Spectators seemed to feel much the same way; the stands were half-full for the opening ceremony and a total of only 10,044 tickets were sold for the entire competition, just over 900 a day.

The British complained of being billeted on a “horrid little Pension” and made such a fuss they were moved to a grand hotel, miles away from training facilities. The much-fancied French ice-skating team fell victim to a flu virus, which their captain said left them in “a sad state… coughing, spitting, handkerchief permanently in their hands” at the starting line.

The climactic ice-hockey match turned into a bloodbath. The gold medals were made of silver and a ski-jumping bronze was awarded to the wrong person, an error corrected only 50 years later, when its rightful recipient, Anders Haugen, was 86.

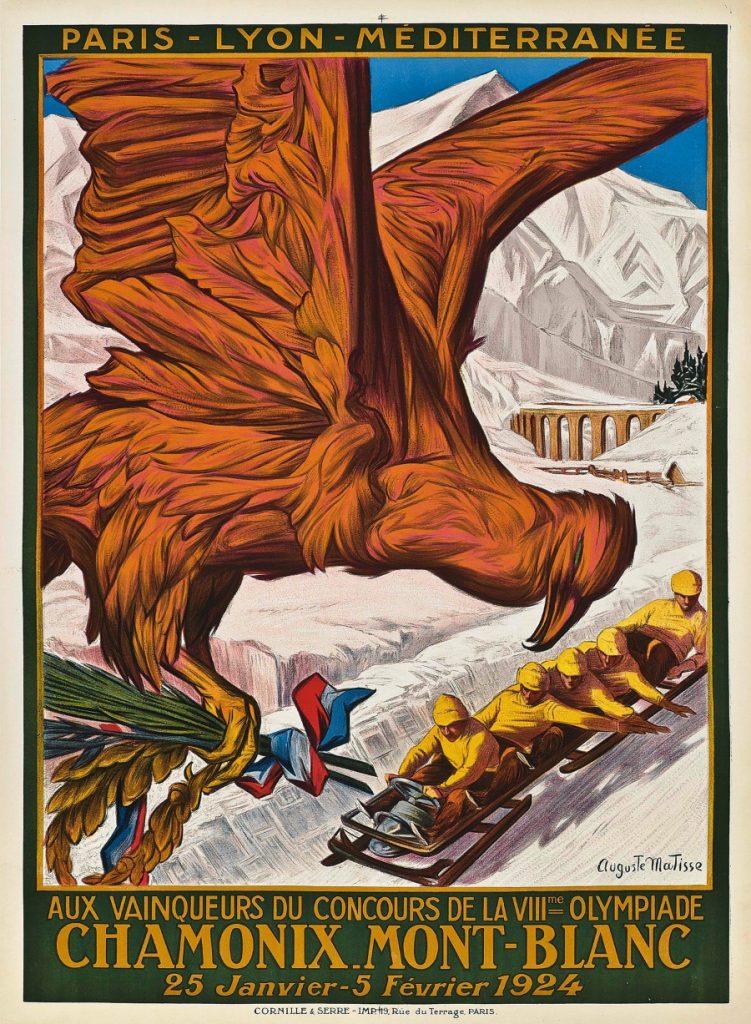

And the event was not even called the inaugural Winter Olympics at all. Just as what American football now refers to as Super Bowl I was originally known as the AFL-NFL championship game, Chamonix 1924 was then just an “international week of winter sport”. In keeping with the chaotic nature of the event, it was a week that lasted 12 days.

But this 12-day week was a triumph, one that would see opposition to the idea of a winter games melt away like that ice rink in the thaw.

That opposition was led by Lord Pierre de Coubertin, the French historian and International Olympic Committee president who founded the modern games.

A 1912 gold medal winner in the long-since-discarded poetry section, Coubertin openly worried that a winter event might put off warm-weather countries from joining the nascent Olympic movement. Privately, he was mindful of upsetting the Nordic countries, which had their own popular games. And besides, the summer games already had room for cold-weather sports; Antwerp had hosted figure skating and ice hockey in 1920.

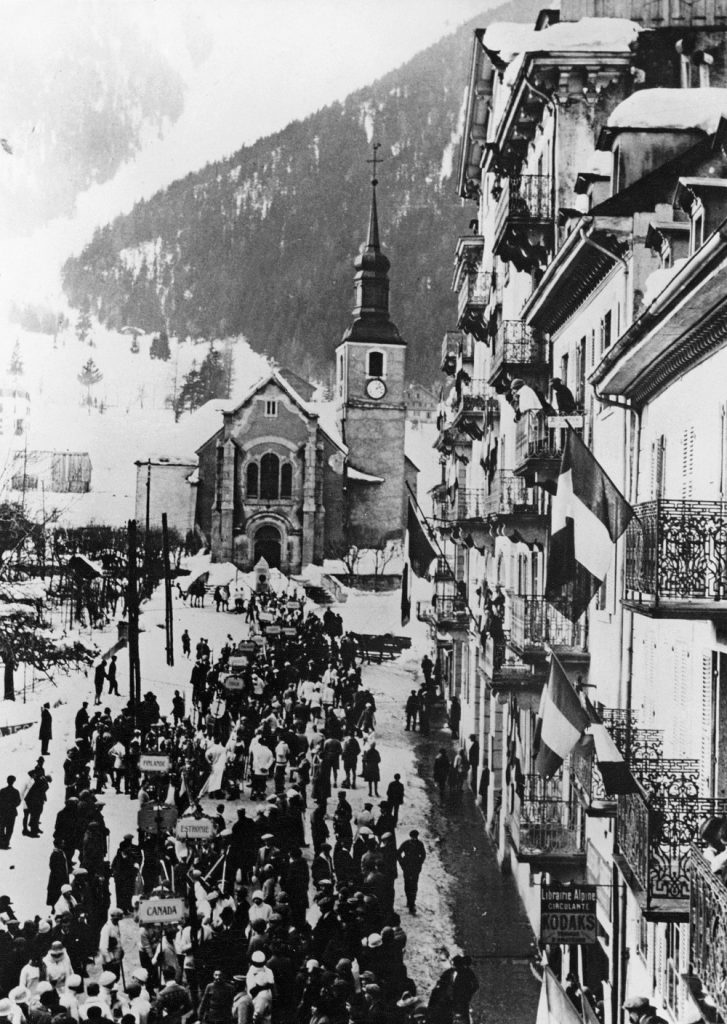

But a year later, an experiment was agreed, and with Paris hosting in summer 1924 – just as it will in 2024 – a French site was sought for the new event. Which was where some of the trouble started. The Alpine village of Chamonix, bordering both Switzerland and Italy, had the slopes and the snow, and it also had a train station thanks to its place as a Grand Tour stop where the wealthy could strap on skis or gaze at glaciers. But the train station was far from where the events would be held, and as now, Chamonix was for the rich. Those who came in 1924 seemed more excited by being seen at parties than going to the events themselves.

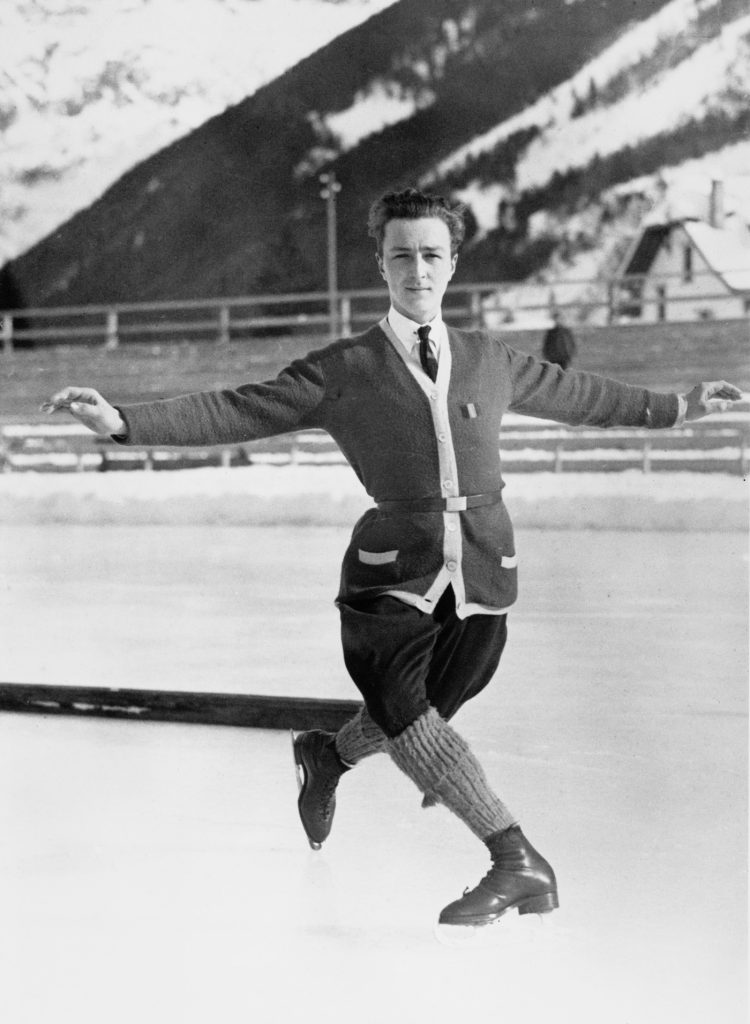

The pattern was set by that opening ceremony, attended by 2,089 paying fans who just managed to outnumber the 294 athletes from 18 countries with their support teams, plus Olympic and local dignitaries and around 200 journalists. But as well as a chill that could crack rocks, as one spectator had it, there was also magic in the air – as evidenced by the ovation the sparse crowd gave to 11-year-old Norwegian skater Sonja Henie, a future Olympic champion and future Hollywood star who appeared in a team blazer several sizes too big for her.

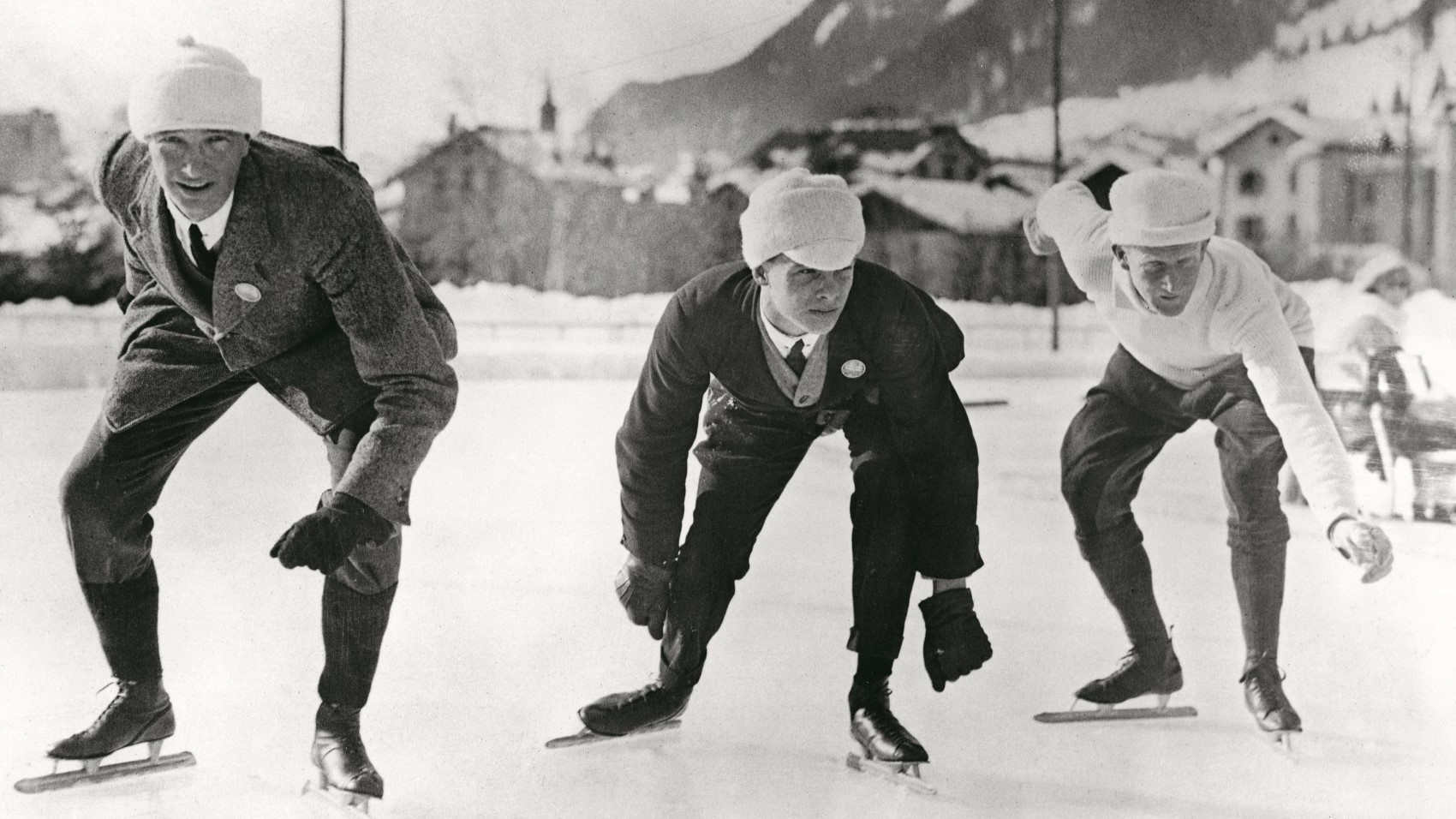

America’s speed skater Charlie Jewtraw was there, and two days later he would win gold in the first event, the 500 metres. “I stood in the middle of the rink, and they played The Star-Spangled Banner,” he told Sports Illustrated in 1983. “The whole American team rushed out on the ice. They hugged me like I was a beautiful girl.” The no-nonsense Finnish speed skater Clas Thunberg was there too. He would go on to win three golds, a silver and a bronze in speed skating, but not bother to attend the closing medal ceremony after a series of run-ins with teammates and organisers. Instead, the part-time builder headed for Paris, ran out of money and had to telegraph his wife to send the funds to return home, where he was greeted by a huge crowd.

Herma Szabo, one of only 11 women to compete, was there too. She would go on to win skating gold, though she was so convinced that she had lost to America’s Beatrix Loughran that she left the rink and was back in her hotel, fully changed, when the Austrian flag was raised. The costume Szabo, whose time at the top of her sport would be cut short by Henie’s irresistible rise, had taken off had its skirt cut above the knee, unlike the trailing skirts of her rivals. It was one sign that change was coming.

There was another in Coubertin’s speech at the closing ceremony. “Among the numerous spectators,” he said, were “many who have discovered sports whose beauty they had never suspected.” Perhaps he counted himself among those who had been taught a lesson by what he called a “school of audacity, energy and willpower”. Within a few months, the idea of a winter games would be approved.

Chamonix 1924 was over. And now the Winter Olympics could begin.