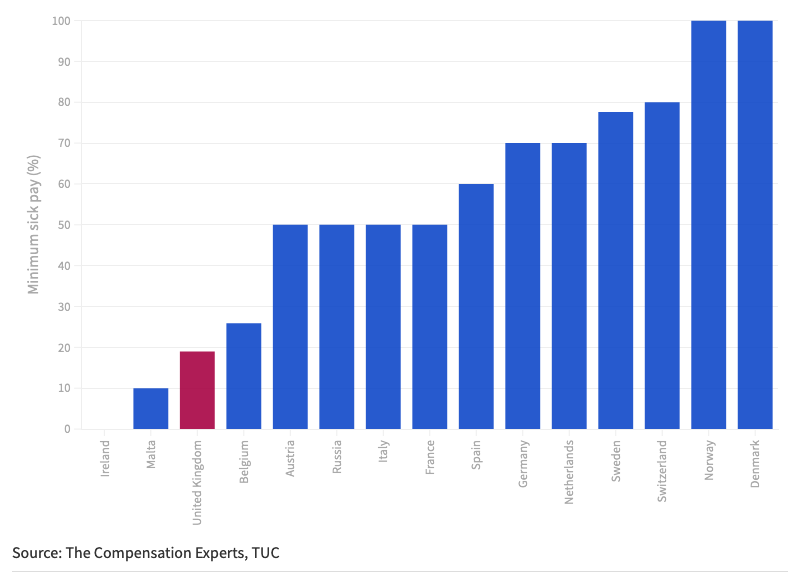

In Parliament on Monday, Boris Johnson drew a backlash from campaigners for comparing the UK’s sick pay to that of Germany, saying: “I’ve often heard it said over the last couple of years that we have a habit of going back to work, or going into work, when we’re not well.

“And people contrast that with Germany, for instance, where, I’m told, they’re much more disciplined about not going to work if you’re sick.”

In March last year, unions had hoped that when statutory sick pay became available from day one when self-isolating – instead of day four under normal circumstances – the change would become permanent. It greatly lifted financial burdens on employees, many of whom contracted Covid.

According to Boris Johnson, we should now “learn to live with the virus” and move on from the days of lockdowns and mask mandates. This means tearing up the protections that many employees had become reliant on. This revoking of pandemic-era legislation will significantly hit the pockets of poorly Brits and, according to the TUC’s Frances O’Grady: “The government is creating needless hardship and taking a sledgehammer to public health.”

While the rate of sick pay remains unchanged, at £96.35 per week up to 28 weeks, the pre-pandemic status doesn’t stack up when compared to other European countries. Germany’s sick pay is higher. It has one of the best rates in Europe, requiring employers to front 100% of wages for the first six weeks an employer calls in sick.

This appears to be one of many knock-on effects too. On average, German employees took four hours to do what UK workers did in five hours in 2016. Britain works longer days on average than Germany, so overall UK workers were 8.5% less productive than German employees.

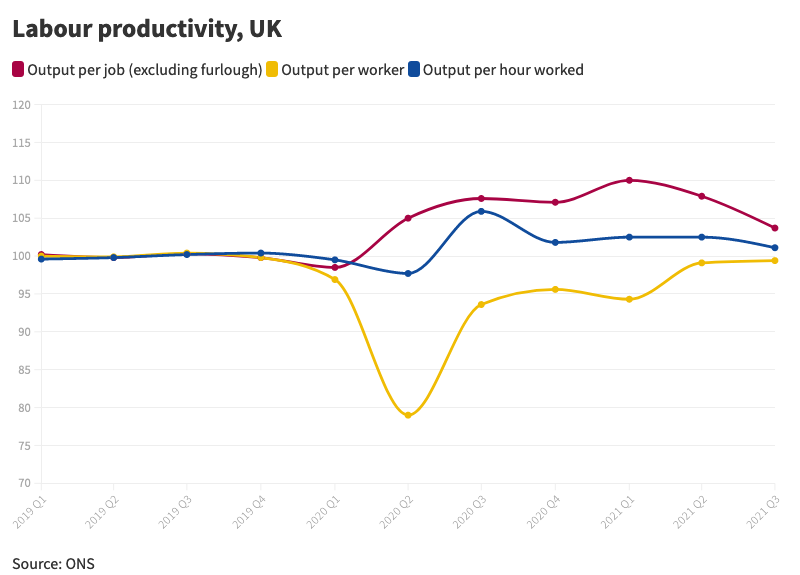

In one study looking at the United States, researchers found organisations offering generous sick pay grew productivity by 7% and profitability by 2%. While this might not seem like a lot, growth of the UK’s productivity is a slow and gruelling process where major incidents, like the pandemic, can tank output per worker to low levels.

Other European countries – namely Denmark, Norway and Switzerland – all fall within the top 10 most productive countries over the last seven years. The trend? They all offer employees 100% of their wages when sick. The outliers (such as the Republic of Ireland) currently have no minimum sick pay, often having longer working hours than states with highly-rated sick pay packages.

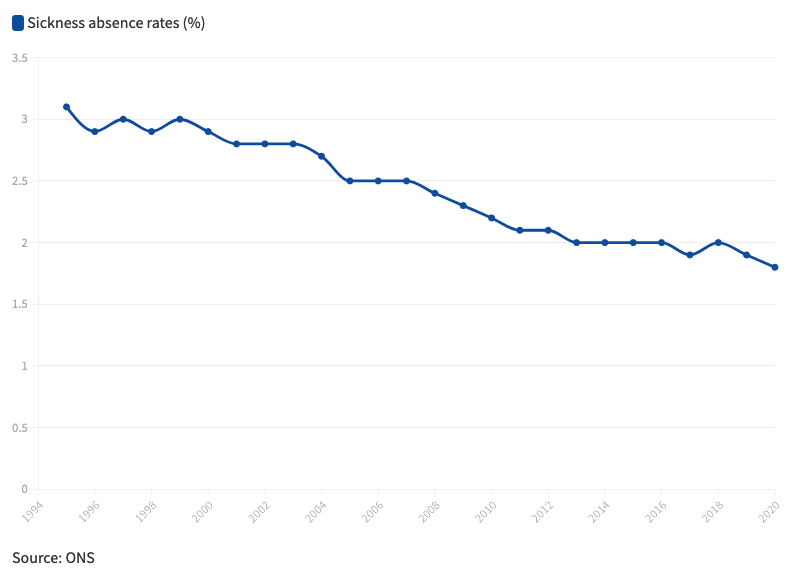

People aged 65 over were the only group to see an increase in absenteeism due to ill health over the decade. There are some fears that increasing sick pay would mean younger employees would take advantage of the extra cash and bunk off work. In Germany, which Johnson uses as his perfect example, data shows the strongest decrease in absence cases among young workers (15–25 years) and the lowest decline among workers aged 45-55 between 2003 and 2007.

Sickness absence rates in Britain are at an all-time low. While Covid led to additional leave, measures such as furloughing, social distancing, shielding, self-isolation and increased home-working appear to have helped reduce other causes of time off, allowing the general downward trend to continue. Since April 2020, Covid accounted for 14% of all occurrences of sickness absence. Key workers in health and social care have seen the largest sickness absence rates in 2019 and 2020.

But there’s a new practice in business. It’s presenteeism. And some, including the prime minister, think it’s a great idea. Unfortunately, it appears to have counterproductive long-term consequences. According to the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development, overworking has more than tripled since 2010. Many employees feel like they can’t switch off. Two-fifths of organisations experiencing these issues are taking no action and the onus is being put on them because statutory sick pay isn’t comparable to other European countries. The UK economy lost almost £92bn in 2019 because of ill-health related absence and presenteeism in the workplace.

Before the pandemic businesses were losing an average of 38 working days per employee to both physical and mental health conditions. With restrictions being rolled back, it’s inevitable that workers will be forced back into the workplace and presenteeism will skyrocket.

Productivity is on the decline. Sickness absence rates have dipped. Making people come into work when they’re ill isn’t going to boost productivity. If absenteeism is at all-time low, then isn’t lifting Covid restrictions likely to damage that? Christina Pagel, a member of the Independent SAGE group, hits the nail on the head: “Supporters of relaxing the measures have often appealed to individual responsibility – whether that’s to voluntarily self-isolate if positive, or to assess our own appetite for risk and behave accordingly. But this misses the point: there is a limit to what the individual can do with a highly infectious disease.”

And there is a limit to how much, to use Johnson’s phrase, a country can “build back better” from the pandemic with a government throwing hurdles in its way.