A big part of me believes that the royal family is the pinnacle of a class system that holds Britain back by preventing it from becoming a true meritocracy, and that given all the advantages the royals are born into, they can hardly go wrong. But a bigger part of me developed a huge admiration for the Queen, not least her skills as a leader. In challenging times, she secured the monarchy for at least another generation and probably much longer than that.

When I interviewed John Browne, the former CEO of BP, for my 2015 book Winners: And How They Succeed, he said: “She ticks a lot of the boxes on leadership. She is clearly good at strategy, instinctively. She definitely has one, and she is good at executing it. She leads a team which is integrated into the strategy. She has adapted, slowly, over a long period of time, while pursuing broadly the same strategic principles, and she has never lost the plot, when there has been plenty of pressure to do so.”

There were thousands of bad headlines, many setbacks and some crushing low points during her long reign, but the monarchy is in as strong a position as it is possible to be in our modern culture of negativity. Parliament’s esteem has fallen, and the stature of government with it; the reputation of business has been damaged; the church no longer commands such a central place in our lives; the media isn’t trusted, nor public services given the respect or benefit of the doubt they once had; the military remains valued but cuts and controversies have reduced their standing; virtually alone among the major institutions, the monarchy has bucked the trend, and much of that is down to the Queen.

One of her closest advisers said, modestly: “We got our crisis in early, before the Internet really changed the terms of trade.” I think there is a lot more to it than that.

Historian turned Labour politician turned V&A museum director Tristram Hunt agreed with the self-deprecating royal adviser, but added: “Something changed about the Queen. She went from being seen as a figure not necessarily in control of the family and the institution to a different place, above it all. Maybe it was the public response to the series of disasters or perhaps the post-Diana moment, where there was criticism yet also an appreciation of some of the decisions and challenges. I think the public felt they went too far and yet she remained the same.”

The Queen and the institution more generally constituted a good case study for many of the key aspects of leadership: boldness, innovation, adaptability, resilience, long-termism, crisis management, turning setbacks into opportunities.

They were fascinating, too, in relation to strategy. The word itself was effectively banned by the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh, who once complained to an official that “the only two people who talked more about strategy and planning than you were Hitler and Stalin”. The Queen saw monarchy as an antidote to politics, and in so far as she allowed herself to contemplate a sense of strategy, it was in “being the Queen” and viewing monarchy as a values system. But she did lead and allow the building of a new team which, whether she and Prince Philip liked it or not, most definitely strategised for their adaptation to a world of change, responding to a sense of the institution losing its way, and losing its goodwill from government.

This was at its height in the 1970s when political opposition to the monarchy was growing, Parliament forced changes to the civil list, and prime minister Jim Callaghan later wanted to make the royal household a department of state. It is easy to forget just how battered the royals were. For the Queen, the personal nadir was 1992, her “annus horribilis”. She and the family were frankly reeling from a succession of personal disasters that saw their standing and popularity fall. “People began to question what the institution was for,” says one of her advisers. “We were descending into a rather grisly soap opera, and just when you thought we were coming up for air, something else would come along and drown us out again. It was truly horrible.”

Andrew Morton’s book, Diana, Her True Story, which was told with the Princess of Wales’s active cooperation, kept global focus on the private life of Prince Charles, this in the same year that Princess Anne divorced her husband and Prince Andrew separated from his wife. And it was the year Windsor Castle caught fire. The fire was described to me by an adviser who was with her at the time as “without doubt the lowest point of all. This was her home, and I can remember standing in the quadrangle, and this woman, who never lets anything faze her, never puts her emotions on display, had the look of someone who just felt everything was going wrong. She looked destroyed.”

Just how low the monarchy had fallen in public esteem was underlined by the response to prime minister John Major’s announcement that the government, rather than the royals, would pay to repair the damage. There was an immediate outcry and the powers that be therefore had to back-pedal, promising that some money would be raised from savings within the existing grant-in-aid, while other funds would be generated by charging for entry to Windsor Castle and by opening and charging for entry to Buckingham Palace as well. These were huge steps for the royals to take, not least because forces of conservatism as powerful as the Queen Mother were totally opposed.

So how did the royal family get from such a low point to one, barely 15 years later, when – at a time of austerity – a global audience of billions enthusiastically watched the grand wedding between Prince William and Kate Middleton?

Her advisers tended to clam up whenever asked directly if the Queen herself felt the monarchy was in danger, but some of them did think so and that suggests she might have had such fears too. One member of her team told me, somewhat dramatically, that the appointment of David Airlie as Lord Chamberlain in 1983 was “the single most important moment in her reign”. To this day, the people he then brought together to help the Queen through a difficult period of her rule do not know if that appointment was made knowing that, for all his aristocratic background, Airlie would be something of an agent of change.

The aide told me: “David Airlie is was a businessman, chairman of Schroders, chairman of General Accident, and he brought a business eye to the household, and frankly saw that it was running out of money, losing the respect of government, and was stuck in the mire.”

Helped by KPMG accountant Sir Michael Peat, who would later become a key adviser both to the Queen and Prince Charles, he presided over a 1,383 page report with 188 recommendations, which amounted to what they called “privatisation” of the household. “The whole plan,” one courtier explained, “was to take back our own destiny from the government and to do that we had to have control of the finances, a proper management structure and then recruit people who were more in tune with the modern way of life.”

That required cultural and mindset changes too, not easily implemented in an essentially conservative organisation. Two parallel bodies were set up, the Lord Chamberlain’s committee, made up of advisers, and the Way Ahead Group, chaired by the Queen, with the Duke of Edinburgh, their four children and other minor members of the family also present. It says something for their relative efficacy that the Lord Chamberlain’s committee still exists, whereas the Way Ahead Group met infrequently, decided little and was eventually disbanded. The broad outlines of a forward vision flowed from a paper written post-annus horribilis by private secretary Sir Robin Janvrin, a key hiring of the Airlie era and one of a small number of officials who worked with the Way Ahead Group, which suggested the ordering and planning of the family’s activities beneath four key planks of strategy: identity, continuity, recognition of achievement and service. The Lord Chamberlain adapted his role from being primarily ceremonial to becoming more like a chairman of the board, with the Queen as CEO.

To an extent, the monarchy’s ability to focus on the long term – something that is denied to politicians, businesses and sports managers who have to worry about the next election, the next quarterly results, the next big match – helped this reforming movement. Interviewed for my book, one leading player in the team told me: “The Queen refuses to accept she needs a strategy; but she does have a vision. It is to do with values, familiarity, certainty, continuity and leadership; much stronger forces than thought or strategy.” He quoted the words of American essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson that the Earth endures and the stars abide. “The Earth and the stars don’t have a strategy. They just are. The Queen just is. That is how she sees herself. Her year is a season. Her day is a mini-season. She moves at the same pace, does the same things.”

Viewed from one perspective, this sounds like a justification of the status quo. But the Queen was looking ahead to her 2002 Jubilee, and was aware that the public support, so essential to the survival of the monarchy, had wavered. She knew that if she was to secure the long-term future of the institution she needed to make changes to win back the affection that the royal family had clearly lost.

“Is it really about affection?” I asked one adviser. “Yes, because the opposite is disaffection. If you have a disaffected public, you have no monarchy. That was always understood, and they were becoming disaffected, and parts of the media were fuelling that for all it was worth.” In fact, the regular polls that the Palace conducted showed that even when parts of the media were in full cry against them, the basic support for the institution, and especially for the Queen, never fell below 60 per cent. But given it was the next generation that was causing most of the negative headlines, the worry as she and the Queen Mother aged was that once they went, that support would fall quickly. Their strategy had to be based on making the institution of the monarchy relevant for the modern age. It had to maintain and develop the Queen’s enduring strength and popularity, but “rescue” the standing of her children, especially Charles.

Strategy is the place to have arguments, not avoid them. For the royal family, the arguments began in earnest in the late eighties and early nineties, but because strong opposing views were held, a compromise had to be forged, with “resisters” (who felt that the storms would pass and that there was no need to “over-react”) tending initially to hold the upper hand, but with Airlie and his team bringing in more outsiders. For her part, the Queen would allow the debate to develop and at various key moments sided with change.

“She genuinely doesn’t have views or ideology,” an adviser told me in 2015. “That means she actually can adapt when she has to. She’s not someone naturally inclined to change but she knows sometimes she has to, and she’s not worried about loss of face.”

It would be wrong to characterise the debate as being between traditionalists and modernisers. It was more a debate between resisters and evolutionaries, and during the early stages, the evolutionaries had to be patient. “Often, it was one and a half steps forward, one step back, sometimes two steps back, so we had to bide our time,” said one. At each moment of setback, the modernisers – another banned word – would accelerate the process of what they called “loosening”.

As one of them explained: “Royal Collection, big bridge crossed despite huge opposition from the Duke and the Queen Mother. [Paying] Tax – huge bridge crossed (helped by Charles). Opening up Windsor, bit of a bridge crossed. Opening up Buckingham Palace, huge bridge. But what was really loosening things was that we were getting in very good people, dispensing some of the old retainers, which wasn’t easy, but building a more cohesive team who were capable of adapting to the change.”

There’s no doubt that Diana’s death in 1997 sent a profound shock through the institution. “For a couple of days that week,” said one former adviser to the Queen, “there was real fear, because we just could not fathom why the public were turning on a grieving family trying to console two young boys. We felt like we had lost our point of connection, lost our bearings, and that was a scary feeling.”

That observation chimes closely with one definition of what constitutes a real crisis: an event or situation that threatens to overwhelm you or your organisation unless the right decisions are taken. And there’s no doubt that Diana’s death did for a day or two lead to a sense that they might be overwhelmed. “It did feel like nothing we had felt before. There were certainly moments when we felt we were losing control. We were behind the game,” said the adviser. For those Palace officials at the forefront of the push for evolutionary change, it was proof that things had not changed enough. As one of the architects of the reforming strategy says: “It was as though the thinking happened in the late eighties/early nineties; then 1992–1997 was like stage one of implementation, slow, but with the sense of direction clear; post ’97 the pace accelerated because the resisters caught up with what was already happening.”

Tony Blair was asked by Lord Airlie to help the Palace with their preparation of Diana’s funeral, and I was involved in the Buckingham Palace planning meetings with a couple of Number Ten colleagues. So big were the crowds in the Mall that the only way to get from Downing Street to the Palace was on foot, and as the week between death and funeral wore on, as the crowds and mountains of flowers grew, so did the mood of ugliness. But I think it’s possible to pinpoint precisely the moment when the potential crisis started to subside. It was when the Queen finally came down from Balmoral Castle, and she and the Duke of Edinburgh spoke to some of the crowds mingling outside the palace, at the same time as Princes William and Harry went to talk to others elsewhere. You could literally feel the pressure on them subside.

Difficult issues remained, however, for example which of the family would walk behind the coffin, with the Duke of Edinburgh clear that Charles should not walk alone, and that his sons should be with him, and details being ironed out to the last minute. One of the most tense discussions between traditionalists and reformers concerned the issue of whether the flag at Buckingham Palace should be flown at half mast, traditionalists arguing it should not, reformers very clear that it should.

The Queen’s own strong instinct was that it should not, given Diana was no longer a royal. Her equally strong instinct had been that she should stay at Balmoral to comfort her grandsons. “She is opposed to anything kneejerk, and she felt it was kneejerk to rush back,” one courtier told me. “She is good at considered change, but so anti-kneejerk that perhaps it makes her less good when precipitous action is called for, because she doesn’t do that, her strength is steadiness, not being ruffled. But as the public anger grew, she accepted the advice of Charles and others to return, and to lower the flag. She operates on instinct and a desire to get things right.”

Her altered stance certainly worked, since the public mood quietened. Broadcaster David Frost turned to one courtier on leaving Westminster Abbey after the funeral service and – in echo of what is so often heard said of such moments – observed: “You will emerge stronger from this, I am sure of it.” Yet days earlier, the same courtier was pondering whether the scale of hostility meant that “skipping a generation”, straight to Prince William after the Queen died – which would certainly have been in line with Diana’s strategy – might be needed to win back popular support.

The crisis over Diana’s death might have panicked some into a wholly new direction, but those at the centre of things after 1997 were careful not to lose sight of the fundamental values the monarchy stood for. What therefore followed was not exactly modernisation – though some officials said they drew lessons from what had happened in politics in recent years – and it certainly wasn’t revolution. It was, if you like, urgent marginal gains. One adviser said that throughout the process he had in mind The Leopard, the classic Italian novel by Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa. It tells the story of changes in Sicilian society during 19th-century Italian unification, and contains the line: “Everything needs to change, so everything can stay the same”.

“We wanted people to notice change without us shouting from the rooftops about it,” one courtier told me. “It was very different to what a politician or a business has to do. As a royal, ‘show not tell’ is easier.” Given the microscopic media attention paid to the royals, it was never difficult to get attention, but it did require buy-in from key members of the family, and everything that would be interpreted as change had to be signed off by the Queen. “She approaches everything with a very pragmatic view. It’s a kind of ruthless common sense. She is very uncomfortable if you try to suggest she does something that is not authentically her, but she does understand even institutions like the monarchy must change and adapt. For it to remain a symbol of continuity, it has to evolve, every day move it forward a click. There is the Queen in a headscarf still out walking with the corgis and there is the picture on our Facebook page or an announcement of something she is doing on our Twitter feed.”

Various patterns of incremental change can be detected after 1997. There was a review of the monarchy’s relationship with virtually every institution of service in the land, “from the Women’s Institute to the SAS’”. A key one involved the way in which the royal family interacted with the public. Officials had noted the multiracial nature of the crowds that had mourned Diana, so now there was a very deliberate attempt to associate the family, and particularly Prince Charles, with ceremonies for new UK citizens, rather than merely emphasising traditional British identity. The royal family also engaged more actively in promoting tourism. And they made more imaginative use of the palace at the time of major celebrations, allowing Brian May of rock band Queen, for example, to stand on the roof and play “God Save the Queen” on his guitar.

Throughout it all, though, the Queen remained centre-stage. As one of the people intimately involved with royal matters throughout this period put it: “Only one person can be the Queen, and that is the Queen; only one family can be royal – so be royal.” He considered her visit to Ireland in May 2011 a high point, telling me that she was “literally the only figure in the world who could make that visit. That was the kind of thing that was lost when the focus was on the family as a soap opera.”

Her handshake with Sinn Fein’s Martin McGuinness, once a member of an organisation that had killed a close member of her family, Lord Mountbatten, and for years had had her on its target list too, was a defining moment, planned only at the last minute. And at the 60th anniversary of the Normandy landings in 2004, when Iraq remained a source of contention between the politicians who attended – George W. Bush and Tony Blair on one side of the argument, Jacques Chirac and Gerhard Schroeder on the other – it was the Queen who made sure the day was not derailed but remained a commemoration. “Not only was she out of the politics but she was from the period being remembered, and as she stood there, you got a real sense of the specialness of her and of the position. Only she could do that.”

Perhaps the most extreme example of this policy of continuity and change was the opening ceremony of the London 2012 Olympics. When the organisers first mooted the idea of a scene with the Queen and James Bond actor Daniel Craig, they assumed the best they could hope for was her permission to use a lookalike. According to Sebastian Coe, when it was put to her by David Cameron in their weekly audience, she said yes, and that she would “play” herself in the palace but perhaps have a lookalike in the scene where she jumps from a helicopter…

“We were aiming very, very high,” said Coe. “We were stunned when she agreed.” But it fitted the covert strategy perfectly. Her instincts gave it the go-ahead. It was an extraordinarily modern thing to do – the Queen and James Bond in the opening ceremony. Yet the film was packed with tradition, with minor roles for the corgis, footmen, Big Ben, Winston Churchill’s statue in Parliament Square, Tower Bridge, black cabs, red buses, the Thames and the Union flag – alongside more modern elements, like the London Eye and a group of schoolchildren being shown the Throne Room.

Of course, a sense of humour is often cited as a key element of Britishness; the Queen showed hers in taking part, and in keeping her role secret even from Princes Charles, William and Harry, who first knew when they saw it unfold in the stadium. But if you look carefully at how she played her role, there was no acting. She remained the Queen. It was one of the highlights of the ceremony, and guaranteed her an even more rapturous reception when she, as opposed to the “Queen” in the helicopter, took her seat – still unsmiling – in the stadium. “She signed off every element,” says one of her team. “It was a great moment for us, because she was in her mid-eighties by then, her standing was totally secure, and what that did was show a truly global audience not just that she had a sense of humour, but that the British public had huge affection for her, and recognised her unique place in their lives.”

Perhaps the difference between the old royal family and the new is best shown in the much more proactive media approach, particularly with regard to TV. The Queen certainly understood the power of television – after all, she was the one who pressed Churchill’s government to have her Coronation filmed and broadcast live. But she never gave a real interview – it’s a reflection of her desire to maintain a sense that the monarch is different. True, back in the 1970s, she did do a ‘walk and talk’ with BBC racing commentator Peter O’Sullevan, and she was once close to doing something with Clare Balding for the Horse Show, but in the end decided the ‘no interview’ rule had served her well, and it became a lifelong vow. It led to a wonderful moment of culture clash in the press office when Larry King Live was told that no, the Queen would not be accepting his invitation to be interviewed live. “Oh no,” came the reply, somewhat ironic in hindsight. “Does that mean she’s doing Oprah?’

In her later years, though, the Queen agreed to a new strategy focused on granting greater – though often very controlled – TV access, giving permission for a succession of projects with which the Palace would to some extent cooperate. Under the guidance of Paddy Harverson, brought in from his role as communications director at Manchester United, Prince Charles did even more. The old ways – “never complain, never explain” – were over.

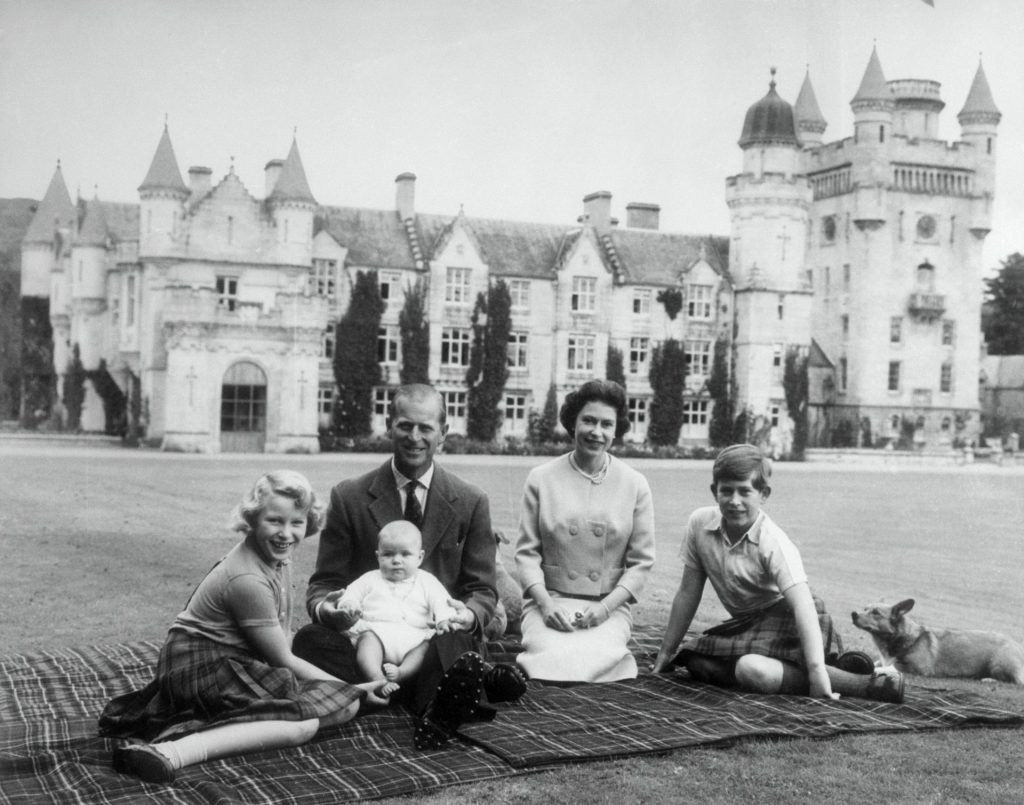

Projecting themselves via TV may sound obvious. But as one courtier told me: “You have to remember that for decades ‘never complain, never explain’ was the strategy.” And of course in the Charles and Diana years, TV played a big part in stirring controversy – the Diana “Panorama” interview and the Prince Charles Jonathan Dimbleby film were almost like acts of war in a brutal PR battle. “They felt scarred, really scarred, and they had to be persuaded this was the way to go,” an adviser said. In addition, the whole household could still be reduced to cringing wrecks if anyone mentioned two previous attempts at major television productions: the 1969 Royal Family documentary, filmed over a year, which showed them talking to each other, having a picnic, watching TV, and generally trying – and failing – to appear ‘normal’; and the “It’s a Royal Knockout”, a not so regal version of a popular TV show. The Royal Family film in particular, which had been recommended to them by a friend in the TV industry, was used again and again by ‘crustier’ elements of the household to argue against allowing greater media access. They considered it an unmitigated disaster that “opened the floodgates” to a more intrusive and prurient media – and that those floodgates should be slammed shut again.

The new openness to the media, which the Queen approved, showed very clearly that lessons from the past had been learned. As one of Charles’s team said, it was agreed that media access should be allowed, but that it was essential “to move the focus from the personal to the professional’. Previously, Charles in particular had been the subject of relentless personal scrutiny, journalists focusing on his first failed marriage, his relationship with Camilla, his out-of-control young sons not on the right path, behind-the-scenes staff issues and personality clashes, murky goings-on below stairs, spending, gifts. “There was so much attention on all that, it was unignorable. So we had to close down the media focus on the private side and start to open up the other, what the royal family actually does as royals. We could not have done one without the other.”

Broadcasters were therefore invited in to discuss specific ideas, with three basic conditions before a project went forward: there had to be relationship of trust with the broadcaster; there had to be a context – an anniversary or a special interest, it could not just be TV for the sake of it; and there had to be an agreement to ring-fence the project so that there was a clear and defined focus. Neither the Queen nor Charles was going to change as a person, so the key was finding new ways of projecting them. It required a new approach and a new mindset, not a revolution.

Little by little, Prince Charles saw the benefits as he cooperated with a film on gardening with Alan Titchmarsh, which received good ratings and reviews, then a film on the 30th anniversary of the Prince’s Trust, with a set-piece interview with Trevor McDonald, then a major (modern) concert event and, coinciding with that, an interview with the three princes, Charles, William and Harry, by popular presenters Ant and Dec. There were one-off interviews and specials with Charles on art, on his painting, on antiques, on the countryside, on the Welsh Guards, on Dumfries House, on composer Hubert Parry. He presented an archive programme about his mother, and he read a weather forecast to mark the sixtieth anniversary of BBC Scotland.

Arguably, Charles stood to gain the most from this approach to TV, but other members of the royal family also became involved. Journalist Robert Hardman’s three-part series on the monarchy, for example, focused more on the Queen. For the Prince of Wales, the aim was to use a series of smaller projects to build up to a landmark documentary for his 60th birthday by John Bridcut, and it was considered a triumph in St James’s Palace, a whole hour focused on who he was, what he thought and what he did for the country – and Princess Diana was not even mentioned. They then started to take the same strategy abroad. They agreed to a profile by CBS’s 60 Minutes. One of Charles’s team says: “They set the whole piece up as ‘you think you know Prince Charles but you don’t’, and then sort of rolled out all our positives about him.”

Charles has since cooperated for programmes with all the established US networks. Meanwhile, the younger princes were being brought into the same strategy. Their view of the media will always be coloured by what happened to their mother; there is no getting away from that. They do blame the media in a way for what happened to her, but they decided if you work with someone you trust you can do a lot. And, of course, given his future role, William knows that he cannot be in a state of permanent warfare with the media.

From top to bottom, what the Firm began to see was the benefits of being on the front foot, creating your own narrative, rather than on the back foot constantly being forced to react to the agenda of others. “Once we showed a new approach could deliver, we started to take command of things much more,” says someone involved in devising the strategy. “So when the tenth anniversary of Diana’s death was looming, we got out with our own plans. Six months ahead, we announced a concert and a memorial service, so before the media had even started to think about it we were out there and the boys were saying ‘this is our mother, our memories, discount everything else’. We were front foot, less reactive.”

Courtiers also point to two very different women who made a big change, one by accident, the second by design: the actress Helen Mirren and Charles’s second wife Camilla. There was nervousness when the royal household heard a feature film was being made about the Queen and her relationship with Tony Blair in the aftermath of Diana’s death. Those at the Palace and at Number Ten who were asked to give background information all, so far as I know, declined to help on the grounds that to say yes might lead the film-makers to claim that the script was in some way “authorised” and therefore wholly “accurate”. To be honest, we all assumed that a hatchet job was being planned.

In the event, however, Helen Mirren played an idealised version of the monarch. “There was a new wave of interest in the Queen, and a new wave of popularity,” one of her team told me. “It was a piece of luck in a way, but it was a piece of luck that ran with the grain of our strategy. I really do think it was a big thing, a massive moment.” The Palace was always coy about whether the Queen saw it, and what she thought of it. My sense was she had, and that she liked what she saw. “It made everyone see how far we had come,” said the courtier. “The anger over the flag – that was a time of real concern. We all felt very vulnerable. The film was such a sympathetic portrayal of the Queen, and I do think it made people feel differently, and that presented us with a new opportunity to take the new strategy forward.”

As for Camilla, courtiers seemed universally to credit her with a big role in improving things for Charles. “There was a lot of worry before the marriage, about whether they would ever be accepted as a couple,” said one of his team, “but in the event, media coverage has been almost uniformly positive.” She brought happiness to him, stability to the family, legitimacy to the relationship, the Queen was pleased, and it started to feel like a new world almost. It was like lancing a boil. It was definitely a turning point. “She used to have to come in through the back door – not a good image. Suddenly they could go on tour together, and instead of Charles seeming a lonely man, he had company and laughter,” the adviser said. “She also always talks to people more comfortably than the natural-born royals. She had seen it all, she knew the way the media worked, her son was a writer/journalist, she had been around Charles when the mess was happening, and she learned from it and got him to learn from it too.”

When I was writing my book, Charles’ team was clear that his future reign as King would be different to his mother’s as Queen, and different to how he had been himself as Prince of Wales. “There is no defined role for the heir to the throne; there is a defined role for the head of state. But equally, no two monarchs are the same. He will bring continuity, but also change,” said someone who has worked closely with both over many years. “He’s had lots of time to think about it. The Queen started so young. He will be much older. He will bring wisdom and experience. He knows he’ll have to rein himself in a little, but he won’t be silent. He knows they are in a good place but they won’t take it for granted, won’t sit around saying ‘great job’.”

That the institution of monarchy should be in such a healthy state at this transitional moment owes much to the Queen. People said of her that, though possessed of a strong personality, she radiated a sense of calm. Even when press coverage was hostile, she never complained. She also had a powerful sense of duty. When King Juan Carlos of Spain abdicated in 2014, it was made clear that she would never consider doing likewise. At the time, one of her courtiers told me: “She would be mammothly opposed to something like that. It is not a job. It is a vocation. She took a vow of service.”

He went on: “I know you’re against the whole hereditary principle, but let me tell you why it works with the monarchy. It is about humility. You and I, or anyone else who gets anywhere in life, we get there on some kind of merit. We might be clever, we work hard, we climb the greasy pole, and then we make our own decisions about what to do and when to stop, when to change what we do. The Queen and the Prince of Wales are not in doubt for one moment that they did nothing, nothing at all, to deserve to be where they are. They were just plonked there. They are accidents of birth. There was no interview, no selection panel. And that has made them very humble about those positions, and very focused about doing the right thing, and disciplined about duty. To me, that is one of the secrets of her success.

“I do not believe people want a communism of wealth or lifestyle. They like her riding to the opening of Parliament in a gold coach, or driving to a hospital in a Rolls-Royce. But people do want a communism of humanity. She has always understood that instinctively. They know she is different, but they also know she is the same, eats the same things, breathes the same air, understands them and wants them to understand her. That is the communism of humanity, and her understanding of that goes a long way to explaining why even with your views, you see her as a success and a great leader.”

I can honestly say I had never before lumped communism and the Queen in the same thought, but he may well have had a point. Whatever way you look at it, she outlived communism, and saw off republicanism too. She was a very special, and very British, winner.

This is an edited extract from Winners: And How They Succeed by Alastair Campbell (Cornerstone, 2015)