When the Ulster poet John Hewitt wrote “the cloud of infection hangs over the city… a quick change of direction and it/Might spill over the leafy suburbs”, he might have been writing about the current condition of Northern Ireland. As we head into autumn, it faces rising Covid-19 cases, hospitalisations and deaths, and mass confusion around how best to bring the pandemic under some sort of control once again.

But Hewitt died in 1987, and the “disease” he was referring to – sectarianism – is one for which NI has yet to find a vaccine, but which has ironically been blamed for some of the disarray in public health policy.

Covid is a menace everywhere, of course. But only three months ago, daily new cases in NI were fewer than 100, there were no Covid patients in intensive care units, none in ventilation and hospitalisations were in the mid-teens. Only two people died from Covid between June 4 and July 9. It looked as if the crisis was over, thanks to the vaccine roll-out, masks and social distancing.

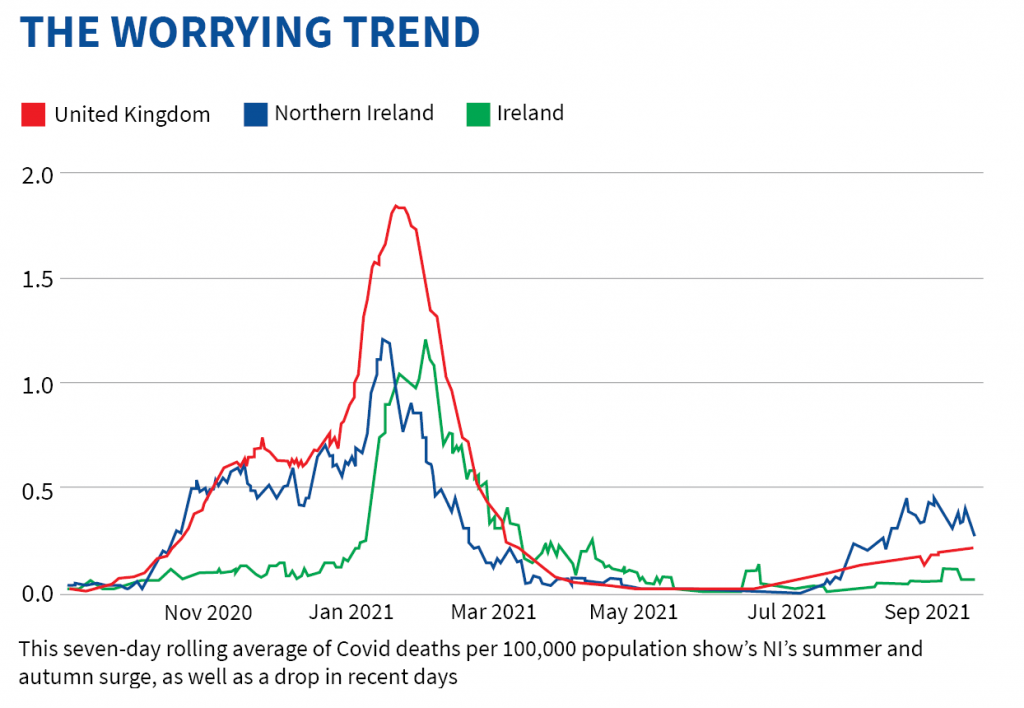

Since July 15, however, there have been more than 1,000 new cases a day, the numbers in intensive care and on ventilators have risen and the death toll over the last seven days has been 45. Some weeks it has been as high as 66. Care home outbreaks currently number 102. There were four in June.

In September the daily death rate in NI reached seven times greater than that of the Republic of Ireland, with the infection rate the highest in Europe and the third highest in the world per capita, behind Georgia and Kosovo.

Paradoxically this disaster has unfolded in a part of the UK where more restrictions remain than elsewhere. Masks are still mandatory in shops and public transport.

The scale of the crisis is such that Northern Ireland’s health minister Robin Swann has called for assistance from British Army medics. The fact that his request came hours after Stormont colleagues launched a £146m scheme to hand out £100 high street vouchers to every adult in NI, ensuring crowded shops and restaurants, only added to the sense of chaos.

The pressures on our creaking NHS provision are indeed worrying. Previous political stalemates meant reform plans weren’t implemented. Now, more than half of the 348,867 people seeking a first consultant appointment will wait over a year.

Beleaguered NHS staff have issued urgent appeals on social media for colleagues to turn in to help deal with overwhelmed A&E departments. Cancer surgery is among operations cancelled due to the Covid emergency.

To compound matters, the new term has brought something close to meltdown in NI schools with staff struggling to manage protocols around infections and parents fearful for children’s safety.

That Northern Ireland has ended up in this dire predicament is all the more perplexing given that it initially benefitted from the UK’s impressive vaccine roll-out and for some months was well ahead of the Republic, which waited on supplies from the EU.

However, by the end of July it had the lowest percentage of double vaccinated people of any UK nation. Last week, NI’s Department of Health revealed 72% of Covid ICU patients were unvaccinated, 8% had one dose, 20% two doses.

Social deprivation has been blamed for the lower uptake of jabs, with working class areas of Belfast including the republican Falls Road and loyalist Shankill suffering among the highest infection rates.

Notably, there’s been vaccine hesitancy among 18-29-year-olds. A gimmick to bolster uptake saw a Belfast nightclub used as a walk-in clinic. Still, since the pandemic began with young people being told they’d little to fear from Covid, it seems unfair to judge them harshly.

Three recent tragedies in NI, however, do offer some insight into the underlying issues around Covid management, especially since the vaccines arrived.

Confusing messaging, for example, has cost lives. Londonderry mum-of-four Samantha Willis, 35, died from Covid two weeks after giving birth to a daughter. The official advice that pregnant women should not be offered the vaccine only changed two months before her due date. Frightened by the earlier guidance and anxious to protect her unborn child, Samantha remained unvaccinated and contracted the virus.

Sammie-Jo Forde, 32, and her mother Heather Maddern, 55, from Co Down, also elected not to have the vaccine. They died from Covid within days of each other, having been treated in the same hospital ward. Both had been working as domiciliary carers, looking after elderly people in their homes.

The risks around unvaccinated carers continuing to care for the vulnerable had been discussed earlier in the year by the NI Executive, but no action was taken. Last week, as the double tragedy made headlines, the deadline passed for care workers in homes in England to get their first jab before vaccination becomes compulsory in October. Politicians at Stormont neither seemed to note the grim irony nor show any inclination to debate introducing similar measures.

The third tragedy – the death of a DUP councillor, Paul Hamill, 46 – highlights the vaccine-resistant cohort that remains among deeply religious Catholics and Protestants in NI. Hamill, who’d been a pastor, had retweeted many posts from vaccine and lockdown sceptics. Some have ethical concerns vaccines are developed from tissues from aborted foetuses.

However, issues around vaccination uptake may offer some insight into the problem, but cannot explain all of it. Complacency has played a part too. In this, Northern Ireland may prove the deadly harbinger of tendencies throughout the UK.

While all summer NI officially maintained restrictions, the reality has been very different. Non-mask wearers abound in shops and on public transport.

Surges in infection coincided with the Euros. While there wasn’t the spectacular official end to the pandemic signalled in London by an England fan sporting a firework up his backside, the country’s bars were packed for the final. The Protestant Twelfth celebrations also saw larger gatherings.

Then, as the crisis took hold, the Stormont Executive disappeared for its annual summer break.

“The people of N Ireland do not deserve this! The handling of #Covid19 in Northern Ireland has been, at best, poor from the beginning,” tweeted Dr Gabriel Scally, the Belfast-born medic and a member of the independent Sage committee.

Failure of messaging, failure of leadership among the political class and failure to implement basic precautions among the most vulnerable, some UK-wide, some local, but all exacerbated by the old divisions.

Tensions between the DUP (which has been the most bullish lobby for full re-opening, “living with Covid”, and a vaccine-only strategy, with the virus as the “new flu”) and Sinn Fein (which has sought to align NI policy with that of the Republic, keeping the borders open to traffic, as well as notoriously flouting public assembly rules they themselves established in the case of the funeral of a senior republican figure last June) have been very much less than helpful.

Throw the Brexit fall-out into the mix, with the NI protocol at the centre of dispute, a looming election, and a variety of internal party wranglings across both main blocs, and it’s fair to say the patience of even the most committed political souls in the general public has been stretched to the limit. The temptation to regard familiar sectarian posturing and attitudes as “normality” proved too strong for the political class.

Northern Ireland’s death toll for Covid-19 is creeping up inexorably towards a number comparable to that of the 3,000-odd fatalities of the Troubles in just a fraction of the time. In our country’s small population, fatalities are more keenly felt.

Hewitt’s poem was entitled The Coasters. Its closing lines may yet be a sorry critique for our times.

“Now the fever is high and raging/ Who would have guessed it, coasting along?/ You coasted too long.”